Earth’s habitability window isn’t as long as assumed.

A recent simulation conducted with support from NASA and associated research partners suggests that life as we know it on Earth may have a surprisingly early expiration point. Using detailed models of solar evolution, atmospheric chemistry and planetary climate, the study projects that conditions suitable for complex life will fade within roughly one billion years. It’s a subtle shift from our everyday concerns but a big one for how we think about our planet’s long-term future.

1. The biosphere will collapse in about one billion years.

In a model described in multiple science-news outlets, scientists found that Earth’s oxygen-rich biosphere may end in roughly one billion years as solar brightening and other changes push the planet beyond habitable limits. This conclusion was reported by Sky at Night Magazine citing a Nature Geoscience study.

That timeline shifts earlier than many earlier estimates, meaning the window for complex life may be shorter than we thought. The modelling makes clear that Earth’s habitability isn’t indefinite—even if it’s still many millions of years away.

2. The root cause is the Sun’s increasing brightness and shifting atmosphere.

According to the NASA Exoplanets site, as the Sun gradually brightens over time, Earth’s surface temperature rises, the carbon-silicate weathering cycle slows, CO₂ levels drop and oxygen production falls, leading to habitat collapse.

Instead of a sudden blast event, what the simulation shows is a creeping decline: rising heat, disrupted cycles, and an atmosphere slowly drifting away from what supports complex life. In effect, the planet becomes less hospitable not because of one disaster, but by so many small changes stacking up.

3. Multicellular life will disappear long before microbes fade away.

The modelling indicates that large plants and animals will lose viable habitats long before microbes and extremophiles do, as derived from the study summarised in Live Science. The report notes that around 1.3 billion years from now, Earth may be uninhabitable for most organisms while microbial life might persist longer.

This means the end of life doesn’t happen in a single instant but follows phases: first the ecosystem we know collapses, then simpler life forms hang on, then eventually even those struggle. It reframes how we view “end of life” on Earth.

4. The timeline gives humanity far more than just immediate worry.

Though a billion years feels far away, this model reminds us that Earth’s habitability is time-limited, not eternal. It may not affect day-to-day life, but it offers perspective: human civilisation is situated on a planet with a middle-aged lifecycle. Recognising that gives long-term planning and planetary stewardship new meaning.

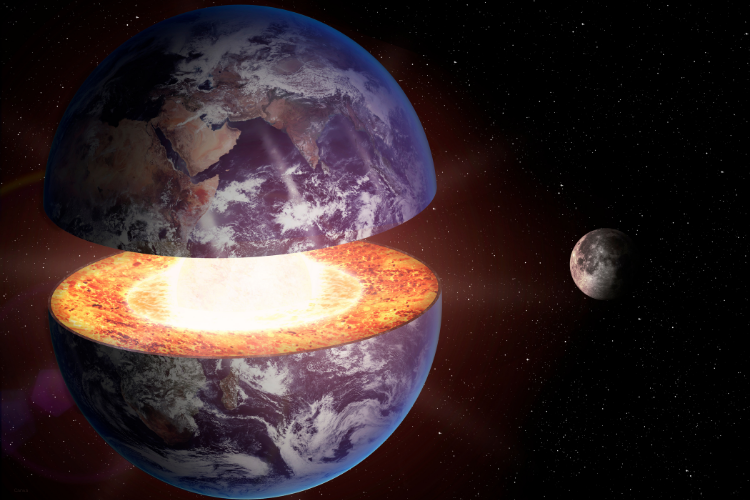

5. Planet-scale modelling is revealing habitability as a dynamic process.

The study leverages supercomputers to link solar evolution, geology and atmospheres, illustrating habitability as something that changes and degrades over time. Rather than assuming Earth will remain ideal forever, the model treats life’s window as finite. That toolset opens new avenues in planetary science—both for our planet and for exoplanets.

6. The findings apply to Earth-like planets elsewhere too.

If our Earth has a finite habitability window, then so do planets around other stars. The methodology used by NASA and its collaborators allows scientists to estimate how long other Earth-analogs might sustain life. In effect, the research helps us understand not just our future but life’s potential timelines throughout the universe.

7. The research emphasises that current conditions still matter.

Even though the model looks far ahead, it underscores that degradation starts quietly, long before the end. Changes in atmospheric composition, climate and biology all feed into a slow decline. That may remind us that caring about Earth’s conditions now isn’t only about the next century—but about extending the thriving phase however much we can.

8. Human civilisation could reinterpret its place in the timeline.

Knowing that Earth’s habitability may phase out over geological timescales prompts reflection on what human civilisation aims for. If complex life is temporary in planetary terms, it might shift how we prioritise knowledge preservation, space expansion or environmental legacy. The idea of “civilisation” becomes tied to planetary timescales, not just human generations.

9. The model is insightful but carries uncertainty and assumptions.

While the simulation is detailed, it still depends on assumptions about solar physics, geochemistry and planetary feedbacks. Factors like tectonic shifts, volcanic activity or unforeseen cycles could alter outcomes. So the projected timeline isn’t a fixed death date—it’s a best estimate based on current knowledge. Recognising that uncertainty is part of being scientifically responsible.

10. The insight reframes how we view life’s future on Earth.

Rather than thinking Earth will remain a cradle for life indefinitely, this research invites us to view our planet as one chapter in a broader geological story—vibrant but not endless. That doesn’t mean despair—it means perspective. Life didn’t just start for us to end abruptly, but the conditions that sustain it will evolve and eventually fade. And now we know more clearly how that path might unfold.