Narwhals are actually real.

Narwhals aren’t mythical, but they act like they never got the memo. That spiral tusk? Totally real. Their disappearing act each winter? Also real. People keep calling them unicorns of the sea like it’s cute, but the truth is, narwhals are built different in almost every way. The stuff they do under the ice isn’t just unusual, it’s barely believable. And somehow, they’ve been pulling it off for centuries without needing an audience.

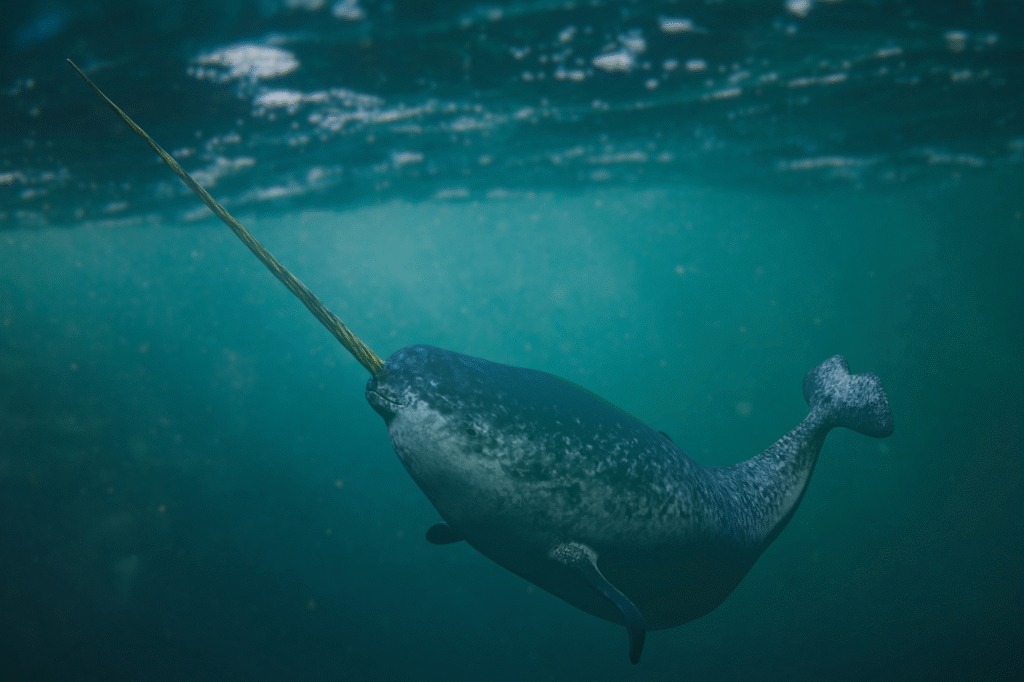

1. Their tusk is literally a tooth that grew out of their face sideways.

Narwhals don’t have horns. That spiral spike is one of their canine teeth, and it grows straight through the upper lip and out into open water, according to Megan Montemurno at Ocean Conservancy. It twists counterclockwise and can reach lengths longer than the rest of their body. Yes, that means they swim with a massive, exposed nerve filled tooth sticking out of their skull like it’s normal.

The tusk isn’t for stabbing. It’s packed with sensory ability and is full of nerve endings, which makes it a kind of biological antenna. Scientists have watched narwhals tapping it against objects, brushing it along each other, and even using it to detect changes in water temperature and salinity.

It also grows in layers, kind of like a tree trunk, which means researchers can actually read a narwhal’s life history from it. Every year, another ring is added. That tusk becomes a timeline of ocean conditions, food access, and even stress events. They’re basically swimming record keepers.

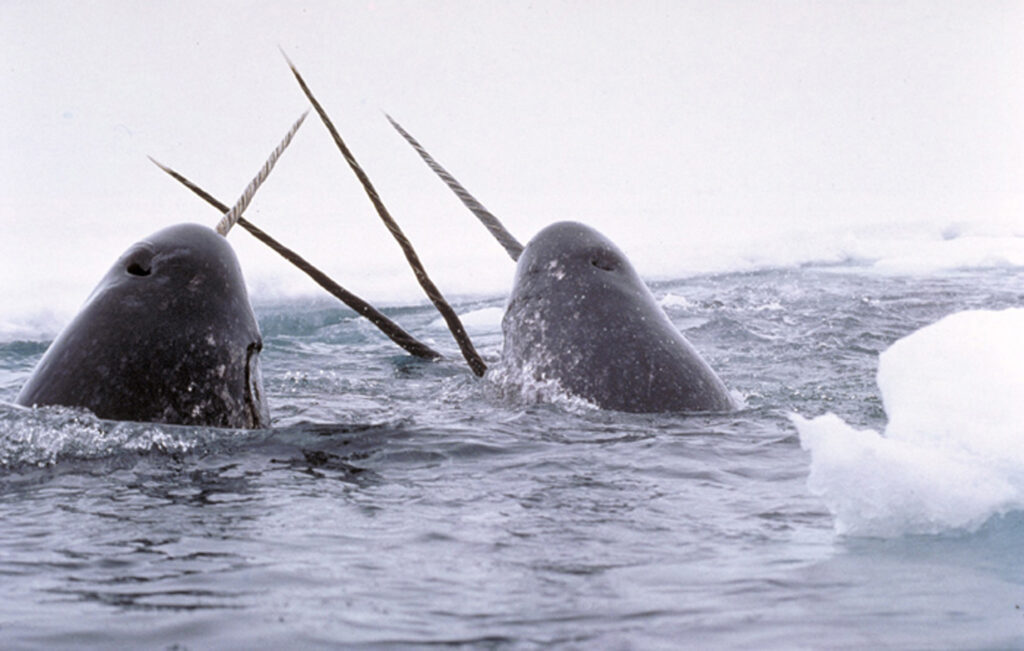

2. Some of them grow two tusks just to keep things weird.

Most narwhals only grow one tusk, but in rare cases, both upper canine teeth erupt and you get a narwhal with double spiral tusks, as reported by the experts at the World Wildlife Fund. It doesn’t happen often, but when it does, the result looks like something out of a fantasy novel that got too confident.

There’s no clear evolutionary advantage to having two, which makes it even more chaotic. They’re not better at surviving, they’re just rare. But that hasn’t stopped narwhal watchers from obsessing over the few individuals known to have pulled this move off. It’s like getting dealt a weird flex in a genetic card game and running with it.

These double tusk narwhals still behave normally, but their skulls show some wild asymmetry from having to anchor two spiral weapons. Researchers use those skulls to study how tusks grow and twist. It’s not random. There’s math behind it. But it still feels like a design glitch that turned out cool.

3. They basically vanish under Arctic ice for months at a time.

Narwhals spend winter months diving deep beneath frozen sheets of sea ice where nobody can see them, as stated by Allison Guy at Oceana. There’s no surface access for miles in some regions, and they navigate it like they memorized a secret underwater map. No GPS, no daylight, just echolocation and ancient instinct.

They have to surface to breathe, so they use tiny cracks and leads in the ice that shift constantly. Miss one and they drown. But they manage it without flinching, diving as deep as 5,000 feet and staying under for nearly 25 minutes on a single breath.

Most of this happens far from where humans can watch. That’s why narwhals are still such a mystery. We don’t know what they eat during those months, how they socialize, or how they handle the pressure changes from those ridiculous dive depths. They disappear into a frozen labyrinth and come out like it was no big deal.

4. Narwhals can flex their heart rate like it’s a remote control.

When they dive, narwhals have the ability to slow their heart rate so drastically that it barely registers, according to Heide Jorgensen at Science News. A typical resting heart rate might be around 60 beats per minute, but some narwhals drop it to four. Not forty. Four. That’s coma level chill, and they’re doing it on purpose.

They use this to conserve oxygen and protect their brains during extreme dives. The slower heartbeat also means less nitrogen buildup in the blood, which helps them avoid decompression issues like the bends. Humans need special gear and training to manage that. Narwhals just flip an internal switch.

Even wild fluctuations in dive depth don’t seem to throw them off. One minute they’re near the surface, the next they’re thousands of feet down. Their body regulates blood flow in real time, choosing which organs get priority like it’s managing a power outage.

5. They make sounds humans literally cannot hear without equipment.

Narwhals communicate using clicks, whistles, and pulsed calls, and most of it happens at frequencies far beyond what our ears can register. Some of their echolocation clicks are so high pitched that even dolphins would raise an eyebrow.

These sounds aren’t just for chatting. They use echolocation to hunt fish in pitch black water, map their environment, and track other narwhals. Scientists have had to attach underwater microphones to ice sheets just to pick up their conversations. And even then, most of it still sounds like digital static to us.

Each narwhal also seems to have a unique signature sound, like an audio fingerprint. It’s how they identify each other in vast, silent spaces where visibility is basically nonexistent. That level of acoustic identity means they’ve probably got social systems way more complex than we realize.

6. Their blood has special proteins that keep them from freezing.

Narwhals don’t get cold the way we do. Their blood contains proteins that help prevent ice crystals from forming, even when they’re swimming in temperatures that would snap freeze most animals. It’s not exactly antifreeze, but it functions like one.

Their bodies also produce a ton of myoglobin, which stores oxygen in muscle and helps them stay underwater longer. This protein is packed tighter in narwhals than in almost any other mammal, giving them a dark red muscle color and letting them survive in hypoxic conditions without stress.

That combo means they’re custom built for long, icy dives that would wreck most other creatures. They don’t shiver, they don’t overheat, and they don’t slow down. It’s not just adaptation. It’s full scale physiological optimization.

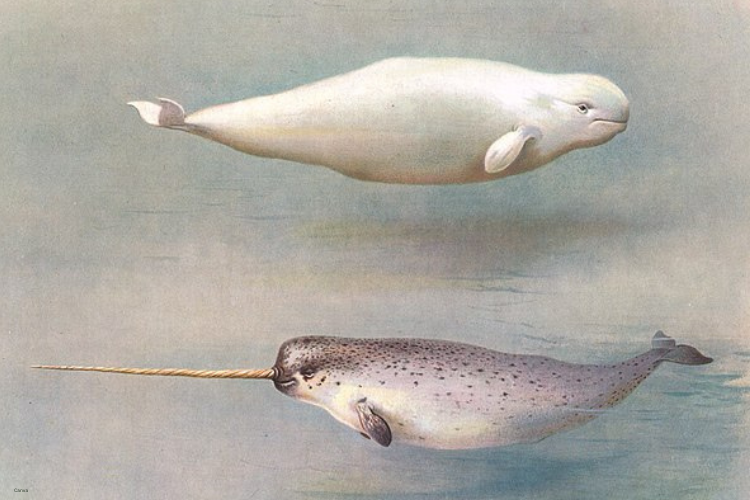

7. They don’t have dorsal fins, which is weird for a whale.

Most whales have that iconic top fin, but narwhals show up without one like they just opted out. Instead, their backs are smooth and slightly ridged, which helps them move more easily under sheets of thick ice. No fin means less risk of injury when navigating narrow cracks in frozen water.

It also helps with stealth. A dorsal fin breaks the water surface and gives away position. Narwhals slide through almost invisibly, especially in low light or icy conditions. That makes them hard to track and even harder to photograph in the wild.

Their lack of dorsal fin also helps regulate heat loss. Less exposed surface area means less contact with cold air, which matters a lot when the water is barely above freezing and the wind is slicing through everything. It’s not a missing feature. It’s a built in survival tactic.

8. Narwhals are picky about where they live and avoid shallow water like it’s cursed.

You’re not catching narwhals chilling in coastal shallows. They prefer deep, cold Arctic zones with steep drop offs and lots of underwater canyons. They stick close to Baffin Bay, parts of Greenland, and northern Canada like those spots are on their yearly subscription plan.

What’s funny is how consistently they ghost entire regions that seem perfectly fine to other whales. Shallow shelf areas? Nope. Warmer fjords? Hard pass. They want depth, and not just for diving. These areas offer better sound travel for echolocation, fewer predators, and more stable ice cover during winter.

That kind of habitat loyalty makes them super vulnerable to climate shifts. As ice melts and water temperatures creep up, their go to hideouts are changing faster than they can adapt. Some scientists are already seeing their migration patterns shift in ways that don’t bode well for their long term chill.

9. Their tusks have up to 10 million nerve endings packed inside.

That giant face tooth isn’t dead weight. It’s a sensory tool that’s basically one huge antenna. Scientists found that narwhal tusks have tons of tiny tubules connected to nerves that can detect temperature, pressure, and even salt levels in the water.

This isn’t just theory. Researchers have observed narwhals reacting when their tusk is exposed to changes in water salinity. That means they might use the tusk to scout out new hunting grounds, find fresh meltwater, or even detect shifting currents before storms roll in.

It also might explain why they tap their tusks together during group interactions. That move was once thought to be aggressive, but now some think it’s a sensory check or a weird kind of data exchange. Whatever it is, the tusk isn’t just decoration. It’s function layered in flex.

10. They don’t thrive in captivity and nobody has ever kept one long term.

Aquariums have tried. It never goes well. Narwhals don’t adapt to enclosed spaces, and most attempts to house them in captivity have ended quickly. They either stop eating, get disoriented, or suffer from stress so severe that they can’t survive more than a few weeks.

Their refusal to adjust has a lot to do with how dependent they are on deep dives, ice patterns, and long distance navigation. They’re built for a very specific lifestyle that doesn’t translate to tanks, no matter how massive or high tech.

That’s why we know less about them than we do about species that are easier to study up close. If you want to understand narwhals, you have to go to them. And even then, they don’t make it easy. They’re good at staying just far enough out of reach.

11. Males sometimes grow bigger tusks just to show off.

The tusk might have sensory functions, but it also doubles as a flex. In male narwhals, bigger tusks often equal more social dominance. They’re not fencing or brawling, but there’s definitely a visual ranking system that plays into mating and status.

Scientists have observed males lining up and comparing tusk length like they’re in some kind of frozen runway show. They might tap tusks, mirror each other, or do little side by side swims that look casual but are absolutely not casual.

What’s still up for debate is whether females care about tusk size the way males do. Some researchers think it matters. Others think it’s more about male social order than actual mating success. Either way, the longer the tusk, the louder the energy.

12. Narwhal skin is so rich in vitamin C that Arctic communities consider it survival food.

Called muktuk, narwhal skin and the thin layer of blubber underneath are traditionally eaten raw by Indigenous communities. It’s not just cultural. It’s survival. That skin has more vitamin C per ounce than oranges, and when you’re living in remote Arctic regions, scurvy is a very real concern.

The texture is chewy, and the flavor is somewhere between salty and marine, but its nutritional value is elite. It provides energy, essential nutrients, and helps people get through brutal winters without relying on imported food.

What’s even more impressive is how long communities have known this. They’ve passed this knowledge down for generations, and it’s part of a broader understanding of how to live sustainably off the land without wasting anything. Narwhals aren’t hunted casually. They’re respected and used with intention.

13. They spend most of their life in darkness under sea ice.

For several months each year, narwhals live under a ceiling of ice with barely any daylight. It’s not twilight. It’s pitch black. They navigate, hunt, and socialize in this space with no visual cues and no margin for error.

Their reliance on echolocation becomes everything. Sound bounces off ice, reflects through narrow tunnels, and helps them find breathing holes. If one of those holes closes or moves, the entire group has to adapt fast. There’s no backup plan.

Despite all that, they seem totally unbothered. The darkness doesn’t mess with their health, their feeding, or their routines. Their bodies are adapted to low light living in a way that would shut most animals down completely.

14. Climate change is messing with their travel routes and survival instincts.

Narwhals have been using the same migration corridors for centuries. Those paths are burned into their instincts. But as Arctic ice melts earlier and refreezes later, those familiar routes are breaking down, and some narwhals are getting caught in places they can’t escape from.

There have been increasing reports of entrapments, where narwhals surface through ice holes that later freeze shut. Without enough breathing spots, they die. And because they’re so ice loyal, they don’t always take the obvious detour to open water.

The shifting climate is also introducing more noise, more ships, and more environmental stressors into their quiet habitats. Their echolocation gets scrambled, their food sources move, and their instincts are tested in ways evolution never prepared them for.

15. Scientists can track narwhal stress just by analyzing their tusk layers.

Each layer of tusk records more than just age. It captures hormone levels, which means researchers can read it like a biological diary. Spikes in cortisol, the stress hormone, show up in periods when food was scarce, temperatures changed, or human activity increased.

Some tusks show patterns of chronic stress that line up perfectly with changes in sea ice cover or the introduction of nearby shipping lanes. It’s physical proof that narwhals are reacting to the world around them, even when they seem chill on the surface.

This kind of data gives researchers a tool they never had before. They can now link long term climate shifts and human impact directly to individual animals, building a more detailed picture of what survival looks like in the melting Arctic.

16. There are fewer than 200,000 narwhals left and they’re vanishing quietly.

They’re not extinct, but they’re not exactly thriving either. Narwhal populations are estimated at under 200,000 globally, with most concentrated in a few Arctic zones. Because they’re hard to study and even harder to count, their decline hasn’t gotten the kind of attention it deserves.

Their numbers are vulnerable to everything from increased Arctic shipping to oil exploration to changing ice conditions. Even slight shifts in their environment can have ripple effects on feeding, migration, and breeding.

What makes it worse is how invisible they are. They don’t show up near cities, they don’t make noise at the surface, and they don’t go viral. But their story is one of the clearest signs that Arctic ecosystems are being pushed to the edge—and they’re taking creatures like this with them.