A quiet shift in strategy hints at bigger ambitions.

For decades, NASA has scanned the cosmos for planets that resemble home, mostly as a scientific exercise, occasionally as a dream. Now the language is changing. Recent announcements suggest the agency is no longer just cataloging distant worlds but narrowing its focus with intent. New missions, revised timelines, and sharpened priorities point to something more deliberate. The question is not whether Earth-like planets exist, but how close NASA believes one might be, and what finding it would mean next.

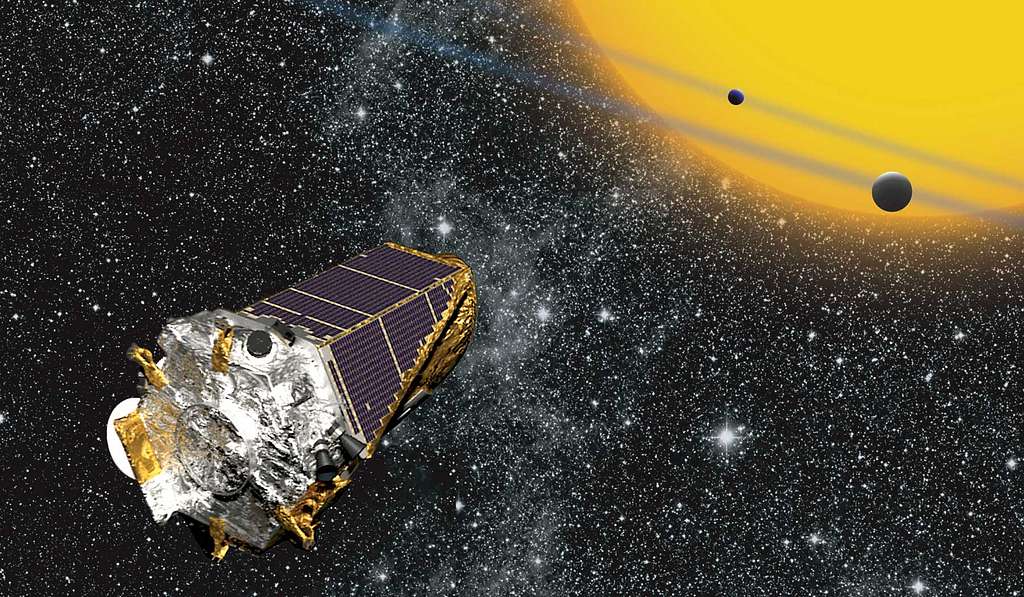

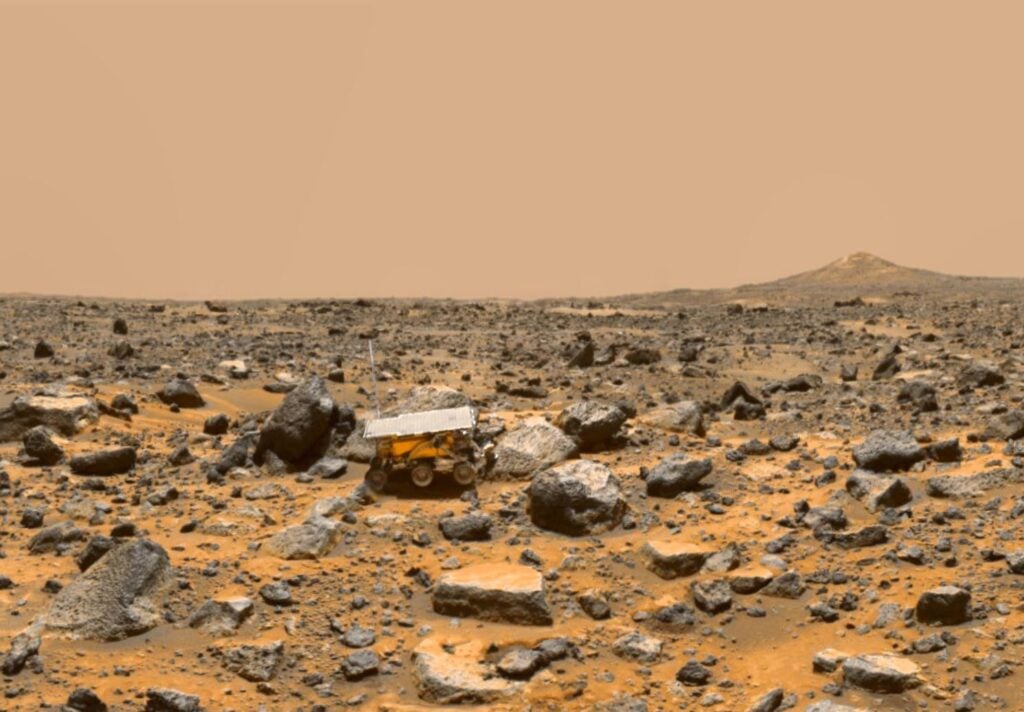

1. Kepler’s discoveries still shape the search today.

The Kepler Space Telescope, which retired in 2018, set the foundation for how we think about exoplanets. Its steady gaze revealed thousands of worlds by tracking the tiny dips of starlight as planets passed in front of their stars. This method transformed planetary science, making it possible to move from guesses to confirmed data. According to NASA, many of the current 6,000 planets on record were identified through Kepler’s work. Its findings remain the backbone of today’s catalog, guiding how astronomers direct their new instruments and ambitions.

2. TESS is filling in the nearby neighborhood now.

Unlike Kepler’s deep stare, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) scans nearly the entire sky. Its job is to find planets close enough for detailed study, focusing on bright, nearby stars that future telescopes can investigate more deeply. The survey has already uncovered hundreds of candidates and continues to add more at a rapid pace. Many of these discoveries orbit stars visible with small telescopes from Earth. The advantage is practical: nearby planets are easier targets for follow-up, as reported by the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

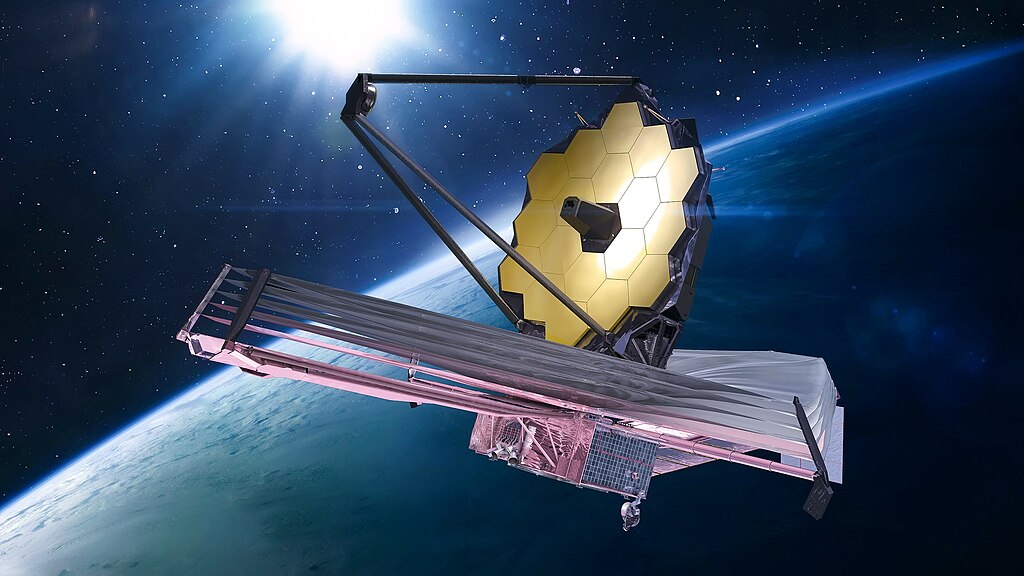

3. Webb is pulling atmospheres into sharper focus.

The James Webb Space Telescope has shifted the conversation from simply finding planets to analyzing them. By measuring starlight passing through a planet’s atmosphere, Webb can detect gases like water vapor, methane, or carbon dioxide—signatures that hint at habitability. As discovered by NASA researchers, Webb has already identified atmospheric components on distant exoplanets. This detail brings scientists closer to answering the question of whether life-supporting conditions exist elsewhere. Webb’s role bridges the gap between raw detection and understanding the chemistry that makes a planet more than just rock and gas.

4. Super-Earths could hold the most potential.

These planets, larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune, appear frequently in exoplanet catalogs, though none exist in our own solar system. Their size suggests stronger gravity, which could support thick atmospheres or oceans. Scientists debate whether that makes them better or worse candidates for habitability, but their abundance makes them compelling. With each new discovery, astronomers refine models of what conditions could allow life to take root. They’ve quickly become some of the most studied targets in the ongoing search.

5. Multi-star systems complicate the habitability question.

Some exoplanets orbit stars with one or even two stellar partners, creating complex gravitational dynamics. These arrangements challenge how stable climates could be maintained, yet they also broaden the scope of what’s possible. A planet orbiting two stars, for instance, would experience light cycles and seasons unfamiliar to us. While it complicates the checklist for habitability, it also expands the imagination of what forms of life might adapt to such conditions. The findings push science into new territory, blending physics with speculation.

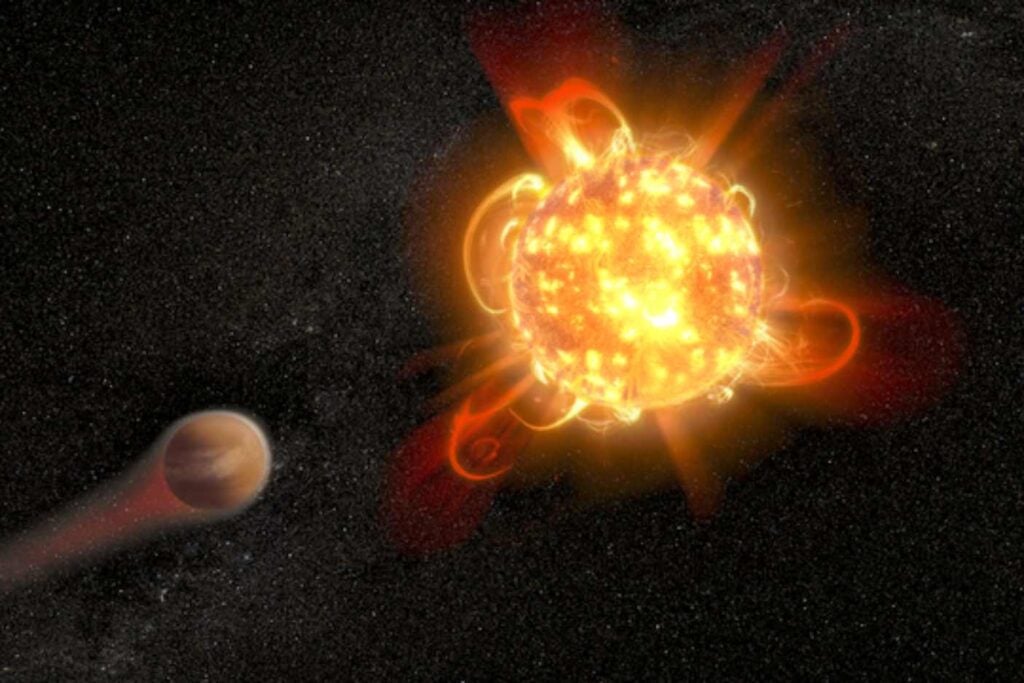

6. Red dwarfs are promising yet risky hosts.

Small, cool stars known as red dwarfs are common across the galaxy, and many Earth-sized planets orbit within their habitable zones. However, their frequent stellar flares can strip atmospheres away or irradiate surfaces. The paradox is clear: they offer abundant opportunities but also steep challenges. Studying these systems gives astronomers critical insight into what makes planets resilient or vulnerable. It’s a category of stars that could hold many Earth-like candidates, if the balance tips in the right direction.

7. Water remains the anchor for most searches.

The presence of liquid water still defines habitability for researchers, even as they explore broader criteria. Planets with conditions that could allow water to pool on the surface earn special attention. Spectroscopy and temperature models help determine which candidates might fall within this zone. Water isn’t the only marker of potential life, but it remains the most practical and measurable. The question that drives the field is straightforward: could life exist here as it does on Earth?

8. Future missions are set to sharpen the focus.

NASA is already planning next-generation observatories, including the Habitable Worlds Observatory, designed specifically to study Earth-sized planets around Sun-like stars. These missions will push beyond detection into detailed analysis, searching for biosignatures that could indicate life. They’ll also provide longer-term monitoring, crucial for understanding planetary climates. Each new mission narrows the gap between speculation and certainty. The tools are finally catching up with the questions.

9. The pace of discovery is reshaping expectations.

Exoplanet science has gone from theoretical to mainstream in less than three decades. What began with a handful of confirmed worlds has exploded into thousands. The sheer scale changes how we think about Earth itself—not as a lone oasis, but as one example in a crowded galactic field. For researchers, the question is no longer if planets exist, but which ones matter most for the search for life. That shift marks a profound cultural as well as scientific turning point.

10. Earth 2.0 might not look like Earth at all.

Even as the term “Earth 2.0” sticks, scientists acknowledge the next habitable world may not mirror ours exactly. It could orbit a different kind of star, carry thicker atmospheres, or support life forms unrecognizable to us. The idea forces a rethinking of habitability beyond Earth’s template. For the public, the vision of a second Earth may stay symbolic, but for scientists, the work is less about resemblance and more about possibility. That gap between imagination and evidence keeps the search both urgent and deeply human.

11. Public engagement is steering the search in new ways.

The hunt for Earth 2.0 is no longer confined to scientists in control rooms—it has become a global conversation. Citizen science projects like Planet Hunters allow ordinary people to comb through telescope data, sometimes catching planets that automated systems miss. That public involvement fuels both discovery and funding momentum. It also changes how space exploration feels: less like a distant pursuit, more like a shared human effort. As the catalog grows, so does the sense that finding another habitable world belongs to everyone, not just the professionals with access to telescopes.