Scientists rethink how humans first reached the Americas.

For decades, classrooms and textbooks told a simple story: the first Americans walked from Siberia across a frozen land bridge called Beringia about 13,000 years ago. But new discoveries are unraveling that narrative. Radiocarbon dating, DNA analysis, and ancient tool findings are now pushing that date thousands of years earlier, and across the water. Evidence from archaeology, genetics, and geology now suggests the earliest people may have sailed along the Pacific coast or even arrived from unexpected directions. The picture that’s emerging is less about a long walk and more about early seafaring ambition.

1. Ancient footprints in New Mexico predate the land bridge timeline.

In 2021, researchers at White Sands National Park uncovered fossilized human footprints dating between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Those prints are thousands of years older than the period when the Bering land bridge was thought to be passable. The discovery forced scientists to reconsider when humans first arrived on the continent. These weren’t brief visitors, they represent sustained human presence long before ice corridors opened. If people were already here that early, they likely arrived by another route, one that didn’t involve walking from Siberia through Alaska.

2. New tool discoveries hint at seafaring origins from Asia.

Stone tools found in Idaho’s Cooper’s Ferry site closely resemble ancient blades used in Japan’s Upper Paleolithic period, as stated by the journal Science. The similarities suggest a possible maritime link across the Pacific. Rather than crossing an icy bridge, early travelers might have island-hopped along the coasts of Russia, Japan, and Alaska by small boats. The Pacific Rim was full of resources, fish, kelp, and sealife, that could sustain this slow coastal migration. This connection makes the idea of an ocean route not only possible but increasingly likely as new artifacts emerge.

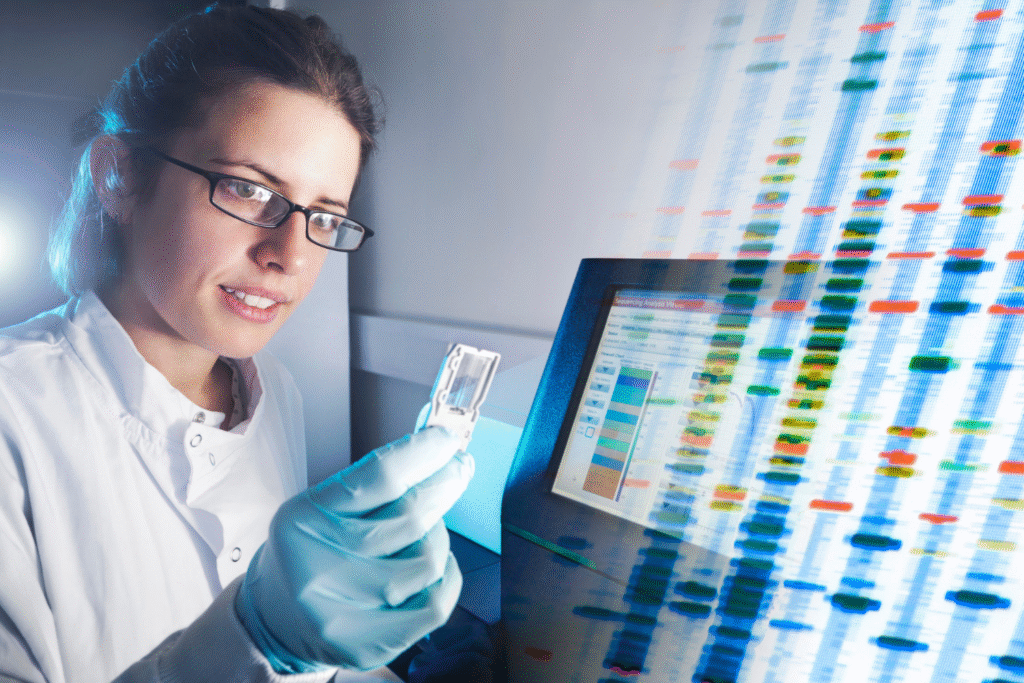

3. DNA evidence confirms multiple waves of early arrivals.

A 2024 genetic study published in Nature traced Indigenous ancestry to several distinct migration events, some possibly predating the Beringian land bridge altogether. Genomic patterns among early American remains and East Asian populations show separate lineages arriving over thousands of years. This diversity implies multiple groups using different routes—some inland, others coastal or maritime. The study dismantles the notion of a single mass migration. It paints a picture of humanity spreading in waves, guided by opportunity and environment rather than a single frozen corridor through the Arctic.

4. The land bridge may not have been usable when people arrived.

Geological models show that much of Beringia was submerged or glaciated during the peak of the Last Ice Age. Even if small areas of land connected Asia and Alaska, they were likely barren, cold deserts inhospitable to travelers. That raises serious doubts about the viability of a land route around 20,000 years ago. The first people to reach the Americas may have been far more resourceful, using coastlines and boats to follow kelp forests rich with food. The traditional “ice-free corridor” simply doesn’t fit the new timing or environmental evidence.

5. Early coastal sites reveal traces of marine migration.

Archaeological digs along the Pacific coast have uncovered early human activity dating back 17,000 years or more, including sites in British Columbia and southern Chile. These settlements appear before inland routes opened, supporting the idea of a “kelp highway”, a marine corridor stretching from Asia to the Americas. People living off fish, shellfish, and seaweed could travel and settle gradually along the shorelines. Researchers believe this path explains how humans reached both North and South America so rapidly after their initial arrival on the continent.

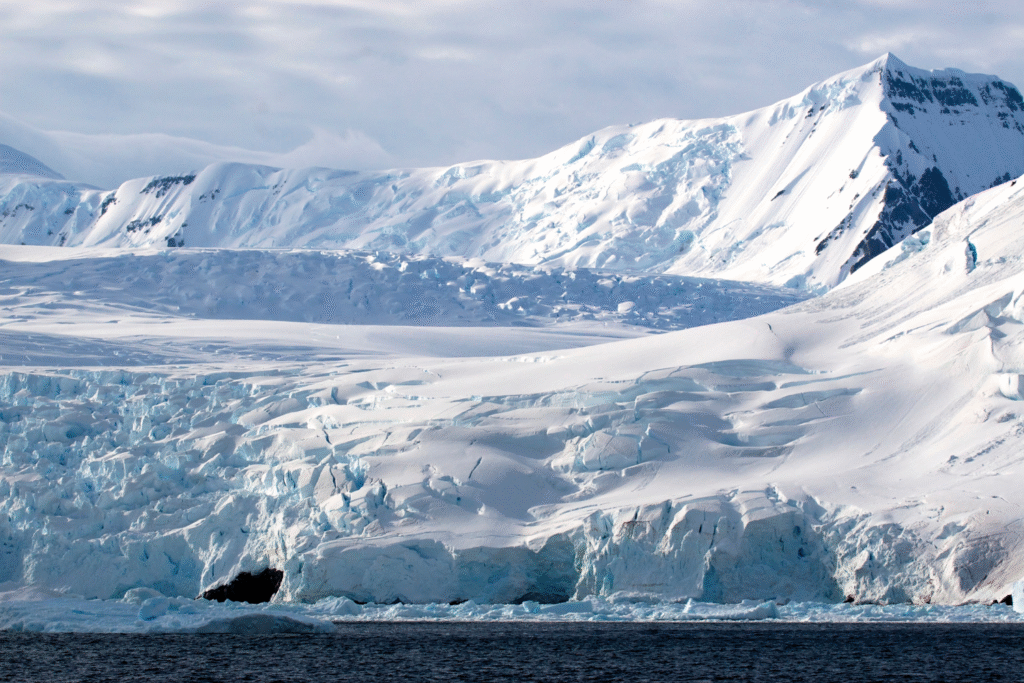

6. Ice-age conditions forced early travelers to the sea.

During the Last Glacial Maximum, much of northern North America was covered by two enormous ice sheets that blocked any land route from Alaska to the interior. At the same time, coastlines offered abundant food and mobility. Hunters and gatherers could move efficiently along the Pacific edge, finding shelter and sustenance as they went. These harsh glacial barriers left the ocean as humanity’s only open highway. What once seemed an obstacle now looks like the most practical pathway for survival—and exploration.

7. Rising sea levels erased ancient coastal settlements.

After the Ice Age ended, melting glaciers caused global sea levels to rise more than 120 meters, drowning the coastlines early people likely followed. Archaeologists believe countless early camps and villages now lie underwater along the Pacific shelf. Marine archaeologists off Alaska and British Columbia are only beginning to explore these hidden landscapes with sonar and submersible drones. Discoveries there could provide the final proof of early seafaring migrations, but until then, the ocean keeps most of this history buried beneath its surface.

8. Indigenous oral histories describe ancestral sea journeys.

Long before modern science suggested coastal migration, Indigenous oral traditions told stories of ocean crossings and shoreline living. Tribes along the Pacific, from Alaska to California, recount ancestors who traveled in canoes, followed marine animals, and lived by the tides. These stories align with archaeological and genetic evidence of early coastal life. When taken seriously, oral traditions reveal an ancestral memory of seafaring long ignored by Western scholars—now validated by new discoveries that echo those ancient accounts.

9. Advanced seafaring skills existed long before the Americas.

Archaeological evidence shows humans reached islands like Australia 65,000 years ago, long before the supposed Beringian migration. If people could sail open ocean to reach Sahul (ancient Australia and New Guinea), they could certainly manage shorter voyages along the North Pacific. Boat-making and navigation were already part of human innovation tens of thousands of years earlier. That means the first Americans weren’t accidental drifters—they were deliberate explorers following coastlines into new worlds.

10. The story of America’s first people is being rewritten.

The combined evidence—footprints, tools, genetics, and submerged landscapes—suggests the Americas were peopled earlier and by more complex routes than once imagined. The image of fur-clad migrants trudging across an icy bridge is fading. In its place rises a portrait of maritime travelers who followed the ocean’s edge, adapting with intelligence and courage. As each new discovery surfaces, it reveals a truth both humbling and awe-inspiring: the first Americans didn’t just arrive—they charted their own course across a world still locked in ice.