Ancient genomes rewrite Europe’s early human story.

Ancient DNA has become a time machine guiding scientists back to the continent’s earliest inhabitants, showing that the origin of Europeans is far more complex than once thought. Recent studies reveal multiple waves of migration, surprising ancestry mixings, and even populations that left no modern descendants. Each breakthrough peels back another layer of the European genetic past, and the story unfolds in ten key moments that reshape what we thought we knew about who “the first Europeans” really were.

1. Early modern humans entered Europe over forty five thousand years ago.

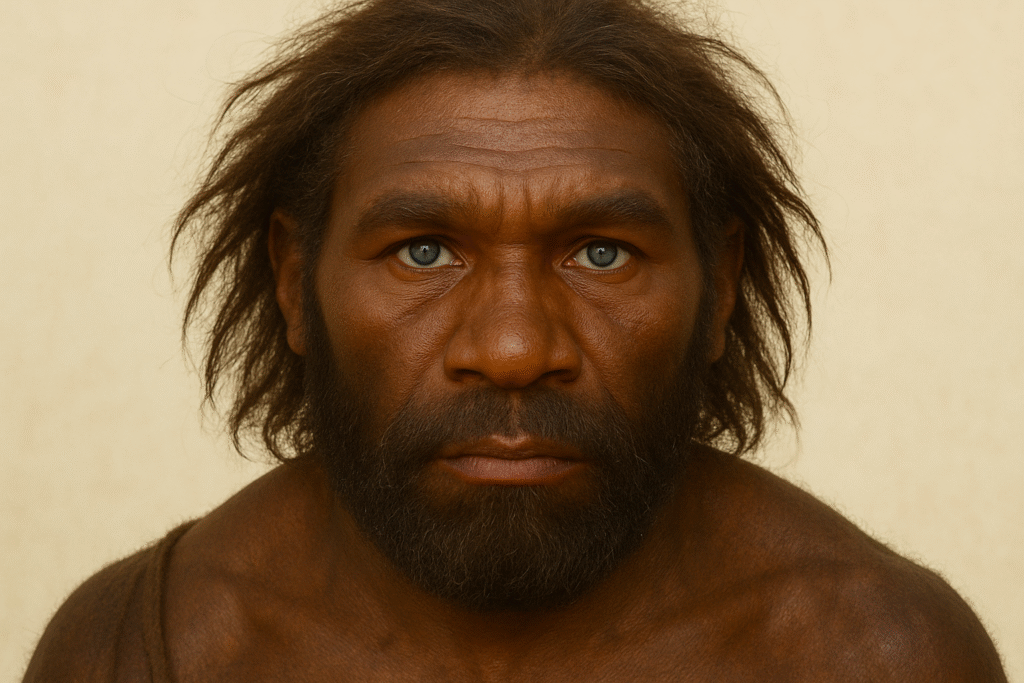

Some of the oldest human genomes in Europe suggest that our species arrived in the continent as early as 45,000 years ago, moving in small groups that mixed with Neanderthals and left surprisingly little direct legacy. As discovered by researchers at the Max Planck Institute and University of Reading, individuals in Ranis and Zlatý kůň show this early presence and intimate inter-breeding. These pioneering populations did not thrive long term, but they set the stage for later migrations and genetic turnovers that built modern European ancestry.

2. Agricultural-era farmers from the Near East reshaped Europe’s gene pool.

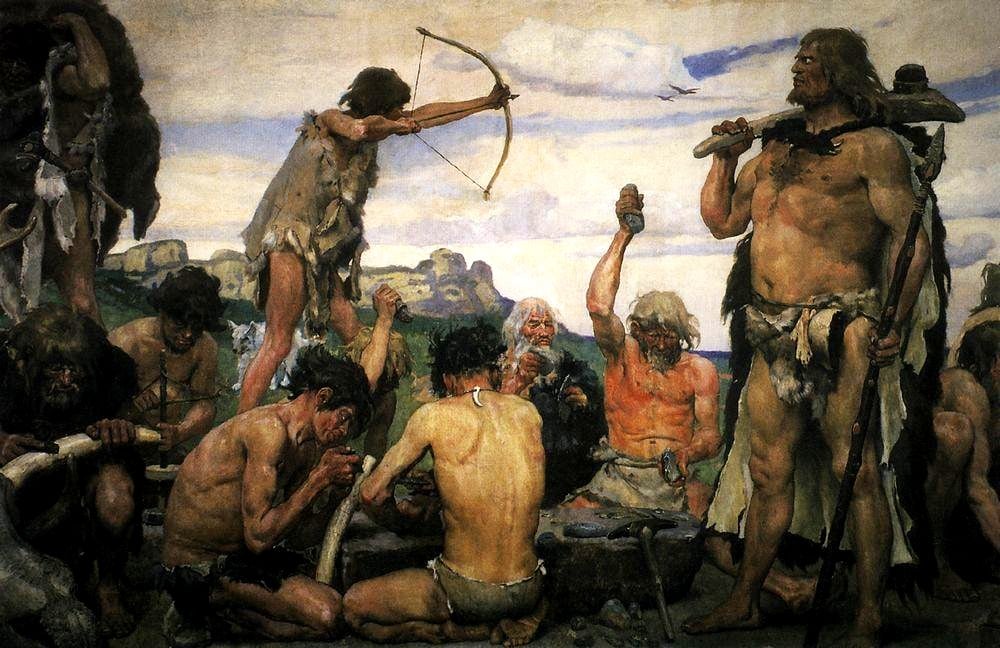

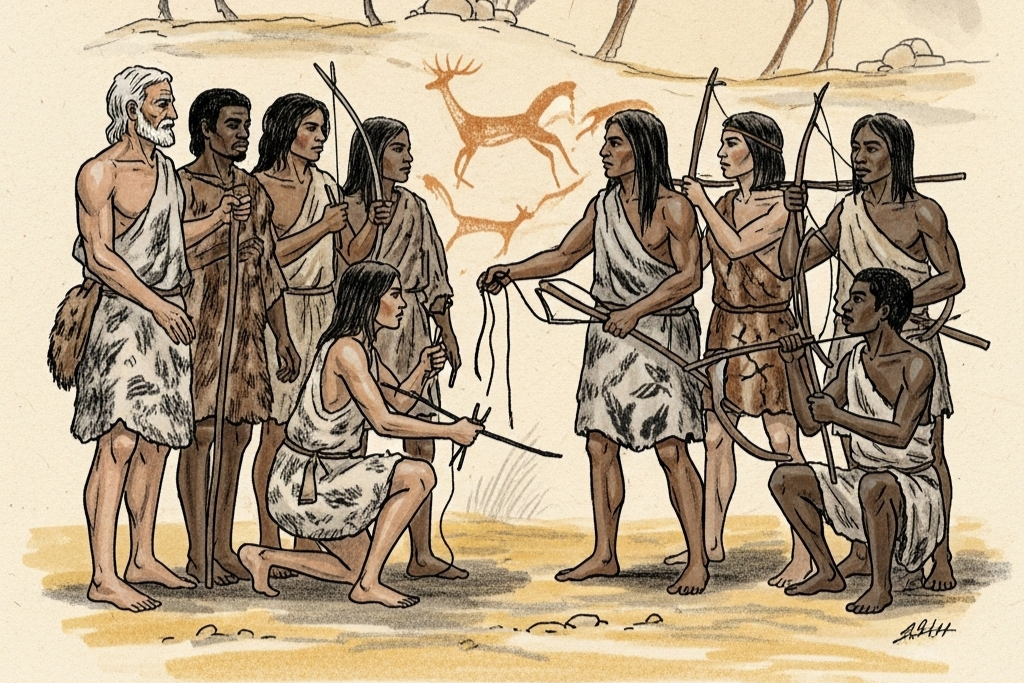

Around 7,000 to 6,000 years ago a major influx of Neolithic farmers from Anatolia and the Near East arrived in Europe and changed the genetic makeup significantly, according to National Geographic reporting. These newcomers brought crop cultivation and new cultural practices, gradually merging or replacing local hunter-gatherer groups. Their arrival didn’t just add genes—it shifted lifestyles, population densities and the relationship people had with land. Understanding that shift is crucial for seeing how European genetics formed from multiple layers of migration and adaptation.

3. A massive migration from the Eurasian steppe deeply influenced European ancestry.

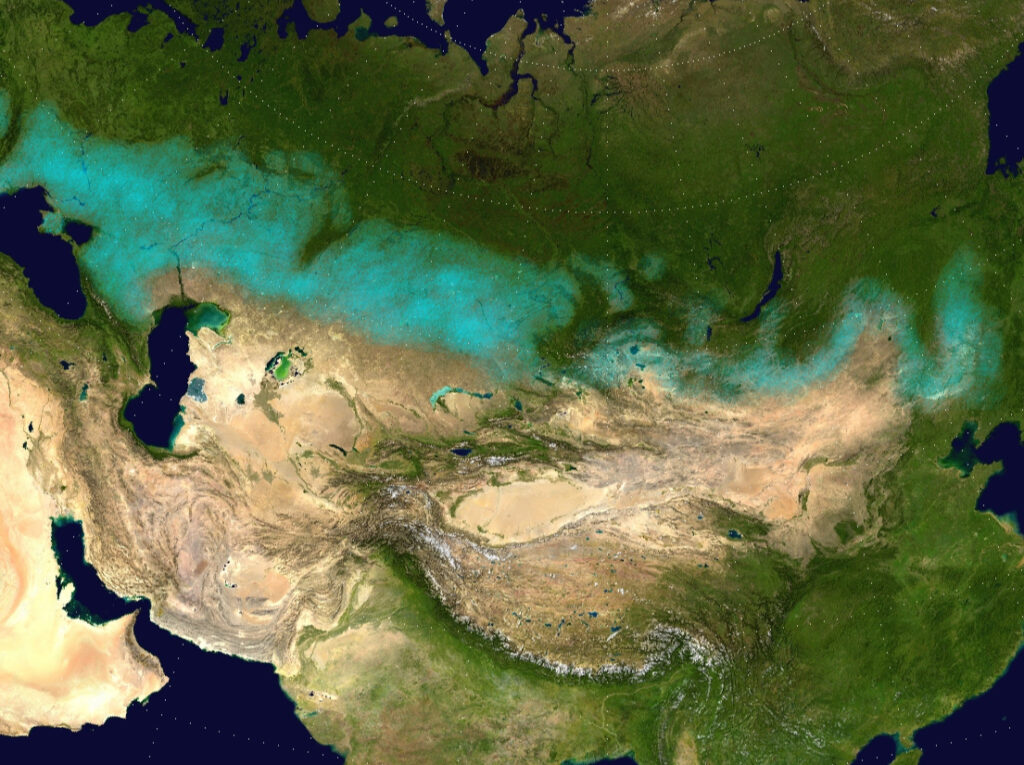

During the bronze age a dramatic movement of people from the Eurasian steppe into Europe brought what we now call Yamnaya-related ancestry, as stated by Harvard Medical School researchers. These steppe populations spread rapidly across many regions, contributing genes, languages and technologies that shaped western Eurasia. The arrival of such groups disrupted or blended with earlier farmer and hunter-gatherer populations, creating much of the genetic substrate found in many Europeans today. The scale and speed of this movement was one of the largest population events in human history.

4. Some early European populations left no living descendants.

Genetic evidence suggests that several early groups who arrived in Europe did not contribute significantly to modern European gene pools and vanished or became absorbed without trace. These shadow populations remind us that the “first Europeans” were not a continuous line but a series of experiments and migrations. Their disappearance didn’t mean they were unimportant—they paved the way for later arrivals, adapting and changing the landscape. Recognising that makes the European story less linear and more dynamic.

5. Genetic turnovers happened repeatedly across Europe’s prehistory.

Instead of one big migration, the genetic fabric of Europe changed many times, with new groups arriving, intermingling and replacing older ones. For example major shifts occurred in the Neolithic, Bronze Age and again in the first millennium CE. These turnovers mean that any given region’s ancestry changed substantially over millennia. The cascading nature of movement and mixing means that “the first Europeans” is not a single people but multiple layered waves of arrival and adaptation.

6. Indigenous hunter-gatherers persisted even after major migrations.

Even as farmers and steppe migrants moved in, hunter-gatherer communities remained and contributed significantly to the descendant gene pools. These groups often adopted certain new practices while retaining elements of older culture and genetics. Their survival adds nuance—Europe was never emptied of its first occupants but rather reshaped through contact and mixing. Appreciating that helps us see modern Europeans as part of a network of ancient peoples rather than descendants of a single founding group.

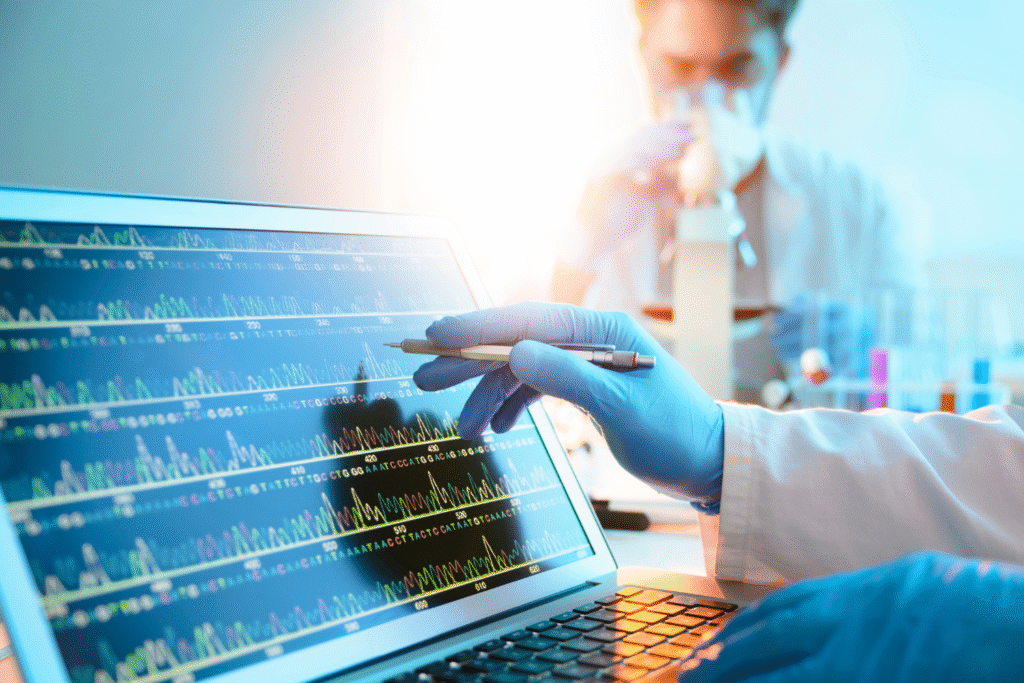

7. Genetic methods now reveal migration details with higher precision.

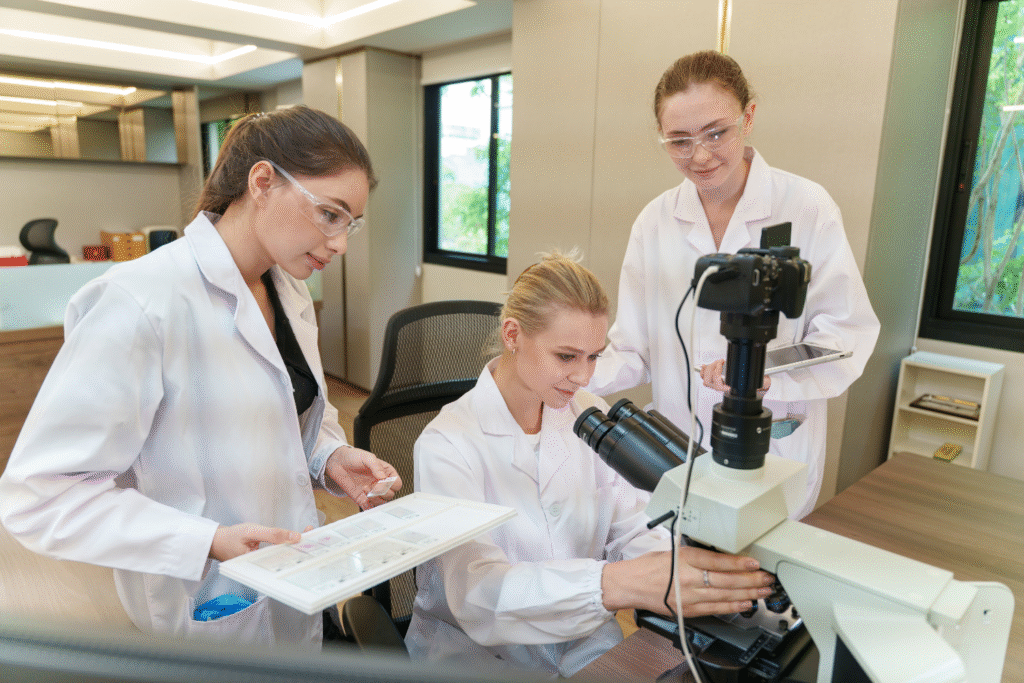

Thanks to new analysis frameworks like Twigstats, scientists are now able to distinguish closely related populations, track subtle ancestry shifts and reconstruct how people moved with greater clarity than before. For instance, the first millennium CE migrations into Scandinavia and Britain have been teased apart in recent studies. These methods allow narratives of European origin to become more detailed and less speculative. As technology advances, the story of “who the first Europeans were” keeps gaining resolution and depth.

8. Traits like skin, eye and lactase persistence evolved in Europe’s past.

Studies show that many of the genetic traits we associate with modern Europeans—such as lighter skin, blue eyes or the ability to digest milk as adults—did not appear immediately but emerged gradually through selective pressures over millennia. Adaptation to new diets, environments and lifestyles drove these changes. Viewing the first Europeans through this lens reminds us that biology and culture evolved hand in hand rather than genetics alone marking identity.

9. Language spread and genetic spread are related but not identical.

While migrations brought genes, they also brought languages—but the two did not always move in perfect lock-step. Some populations adopted new languages without large genetic influxes, while others left strong genetic footprints without obvious language shifts. This pattern adds complexity to how we define “first Europeans” because culture, language and genes each tell different parts of the story. As we refine genetic timelines, we also refine our understanding of cultural change in Europe’s early history.

10. Modern European diversity reflects ancient population layering.

Today’s European populations carry echoes of multiple ancient migrations, interactions and replacements. The genetic mosaic in Europe is the result of hunter-gatherer roots, Neolithic waves, steppe expansions and much more. Recognising that layered heritage helps us appreciate the rich diversity and fluidity of ancestry rather than simplistic lineage claims. In tracing back “the first Europeans,” we uncover not one origin but many interwoven human threads spanning thousands of years.