Household pet care now carries unseen ecological consequences.

Flea prevention is marketed as routine care, but veterinarians across the United States are sounding alarms about consequences far beyond household pets. Chemicals designed to kill parasites do not stay contained. They wash off, spread through soil and water, and enter food chains. Wildlife rehabilitators are reporting unexplained deaths, population drops, and neurological damage in species far removed from dogs and cats. What appears safe at the kitchen counter may be reshaping ecosystems nationwide, raising uncomfortable questions about convenience, oversight.

1. Topical flea medications persist long after application.

Many flea treatments are designed to remain active for weeks, resisting breakdown by water or sunlight. That durability protects pets but creates environmental persistence. When treated animals swim, shed, or are bathed, chemicals enter yards, drains, and waterways. The spread is invisible and ongoing.

These compounds bind to surfaces and sediments. Once released, they affect insects, aquatic life, and birds. Persistence means repeated exposure builds over time, even from individual households acting responsibly.

2. Backyard runoff delivers toxins directly into waterways.

Rainwater carries residues from lawns, patios, and sidewalks into storm drains. Flea treatment chemicals move easily through this system, bypassing filtration and entering streams. Wildlife encounters these compounds far from any pet.

Aquatic insects absorb the toxins first. Fish and amphibians follow. Predators higher up ingest contaminated prey. The pathway is indirect but efficient, spreading harm well beyond urban neighborhoods.

3. Insect populations collapse from secondary exposure.

Flea medications target nervous systems. Beneficial insects share similar biology. Exposure reduces reproduction, coordination, and survival even at low doses. Declines are often gradual, escaping notice.

Loss of insects destabilizes ecosystems. Birds, reptiles, and mammals rely on them for food. When insects vanish, starvation and population decline follow, creating cascading effects that magnify initial exposure.

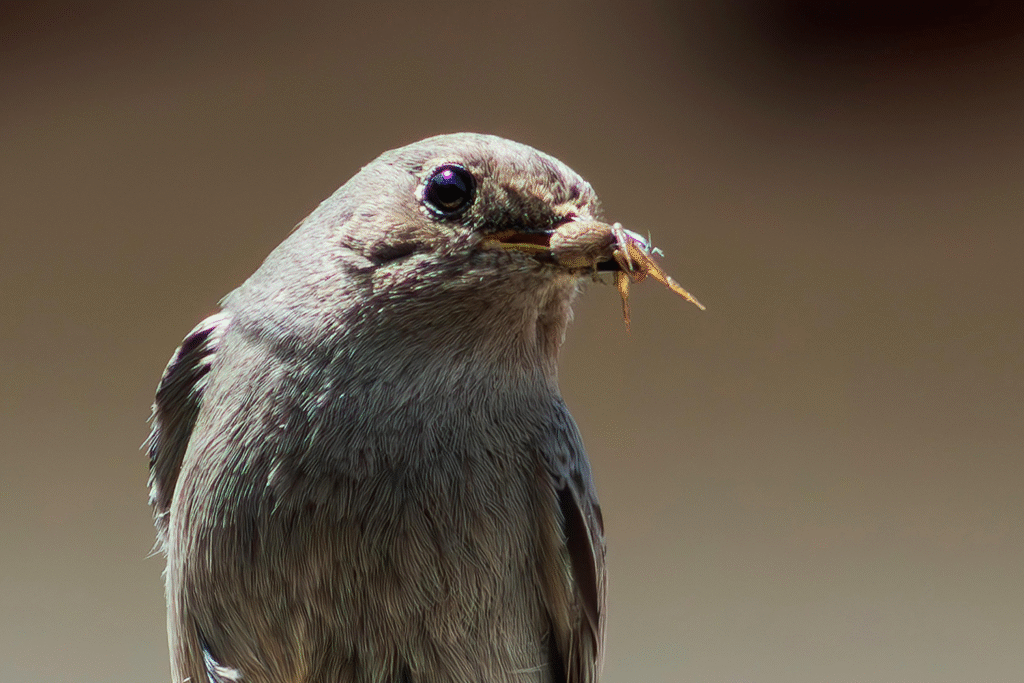

4. Birds suffer neurological damage through contaminated prey.

Songbirds and raptors consume insects and small animals carrying residues. Neurological symptoms appear as tremors, disorientation, and inability to fly or feed. These signs are often fatal.

Wildlife centers report increases in unexplained avian deaths near residential areas. The connection is difficult to trace, but exposure patterns align with widespread flea treatment use rather than isolated poisoning events.

5. Aquatic life shows heightened sensitivity to residues.

Fish and amphibians absorb chemicals directly through skin and gills. Even trace amounts disrupt development and behavior. Reproduction falters before deaths become visible.

Streams near suburban areas show reduced insect larvae and altered species balance. These early changes signal long term damage that may not be reversible once chemical accumulation reaches critical levels.

6. Small mammals accumulate toxins through grooming.

Rodents and other mammals ingest residues while grooming fur contaminated by treated pets or shared environments. Chronic exposure weakens immune systems and reproduction.

These animals form the base of many food webs. When populations decline, predators suffer. The effect spreads outward, linking pet treatments to broader wildlife instability.

7. Cats amplify environmental exposure through roaming behavior.

Outdoor and indoor cats treated for fleas move chemicals across wide areas. Residues spread through fur shedding, soil contact, and predation. Their hunting behavior introduces toxins into wildlife directly.

Even limited outdoor access increases contamination range. The impact compounds in communities where many pets receive routine treatments without environmental safeguards.

8. Repeated dosing magnifies cumulative environmental load.

Monthly treatments create constant chemical presence. Wildlife never experiences recovery periods. Each application adds to existing contamination rather than replacing it.

This steady accumulation overwhelms ecosystems adapted to intermittent exposure. Long term toxicity replaces acute poisoning, making detection and response more difficult.

9. Regulation lags behind real world environmental impact.

Many products are approved based on pet safety, not ecosystem effects. Testing rarely accounts for cumulative runoff or multi species exposure.

Veterinarians and ecologists warn oversight has not kept pace with usage patterns. Widespread adoption outstripped environmental risk assessment, leaving gaps in protection for wildlife.

10. Alternative parasite control methods remain underused.

Non chemical strategies exist but receive little promotion. Environmental management, targeted treatment, and newer approaches reduce exposure risk.

Without broader adoption, reliance on chemical solutions continues. Veterinarians increasingly urge reconsideration, recognizing that protecting pets should not come at the expense of surrounding ecosystems.