Ancient ice is releasing unfamiliar biological surprises.

In the frozen soils of the Arctic, time does not move the way it does elsewhere. Ice locks away organisms, heat, and history in near perfect suspension. As the planet warms, that lock is loosening. Scientists are now uncovering viruses that last circulated when humans were still painting caves. The discovery feels distant, yet the implications drift closer each year as permafrost thaws and long buried material returns to the surface.

1. The virus was revived from ancient Siberian permafrost.

Researchers extracted frozen soil samples from northeastern Siberia where permafrost has remained intact for tens of thousands of years. Inside that soil, they identified viral particles still capable of infecting single celled organisms. According to Nature, laboratory tests confirmed the virus could replicate after thawing, proving its biological machinery survived intact through deep time.

The finding surprised researchers because it demonstrated resilience far beyond previous expectations. The virus was not dangerous to humans, yet its survival alone raised new questions. If one virus can remain viable for twenty millennia, others may also persist, waiting silently as warming temperatures expose layers once thought permanently sealed.

2. These ancient viruses primarily infect simple organisms.

Most revived viruses so far have targeted amoebas rather than animals or people. This choice is deliberate, allowing scientists to test viability without risking human health. As reported by Science, amoeba infecting viruses act as safe stand ins for studying ancient viral behavior while avoiding ethical or safety concerns linked to human pathogens.

Even so, their existence matters. Amoeba viruses share structural traits with more complex viruses, meaning they offer clues about long term viral survival. They also demonstrate that permafrost acts as a biological archive. Unlocking that archive reveals how viruses evolve, persist, and potentially reemerge when environmental conditions allow.

3. Thawing permafrost increases exposure pathways over time.

Permafrost thaw is not uniform. It collapses unevenly, releasing soil, water, and biological material into rivers and ecosystems. According to the World Health Organization, climate driven environmental changes can alter disease exposure pathways, especially in regions where human and wildlife activity overlap with newly thawed ground.

As Arctic development expands, people, animals, and microbes interact more frequently. Most ancient viruses likely pose no threat, yet the growing contact zone raises uncertainty. The concern is not panic but probability. Increased exposure means scientists must monitor what emerges, where it travels, and how modern immune systems might respond.

4. Ancient viruses differ greatly from modern human pathogens.

Viruses preserved in ice evolved in ecosystems that no longer exist. Many targeted hosts that are rare or extinct today. That evolutionary distance reduces the chance they could easily infect humans. Modern viruses are adapted to current biology, whereas ancient ones often lack the tools to navigate present day immune defenses.

However, evolution does not erase all compatibility. Some viral mechanisms are surprisingly conserved. This is why scientists approach these discoveries carefully. The goal is understanding, not alarm, recognizing that unfamiliar biology does not automatically equal danger but still deserves respect and close study.

5. Laboratory revival does not mirror real world exposure.

Reviving a virus in a controlled lab requires precise conditions. Temperature, host availability, and containment all shape outcomes. In nature, released viruses face ultraviolet radiation, oxygen, and microbial competition that quickly degrade them. Most would fail before ever encountering a suitable host.

This gap between laboratory success and environmental reality matters. It suggests that while revival proves survival potential, it does not guarantee widespread transmission. The risk lies less in sudden outbreaks and more in gradual ecological shifts that occasionally allow rare interactions to occur.

6. Wildlife contact presents a more realistic concern than humans.

Animals living in Arctic and sub Arctic regions encounter thawing ground first. Grazing mammals, scavengers, and migratory birds interact with exposed soil and water. These species could serve as early contact points for ancient microbes released from ice.

If an ancient virus finds a compatible animal host, it could circulate briefly before disappearing or mutating. Monitoring wildlife health becomes essential. Such surveillance acts as an early warning system, helping scientists understand whether released organisms remain isolated curiosities or enter broader biological networks.

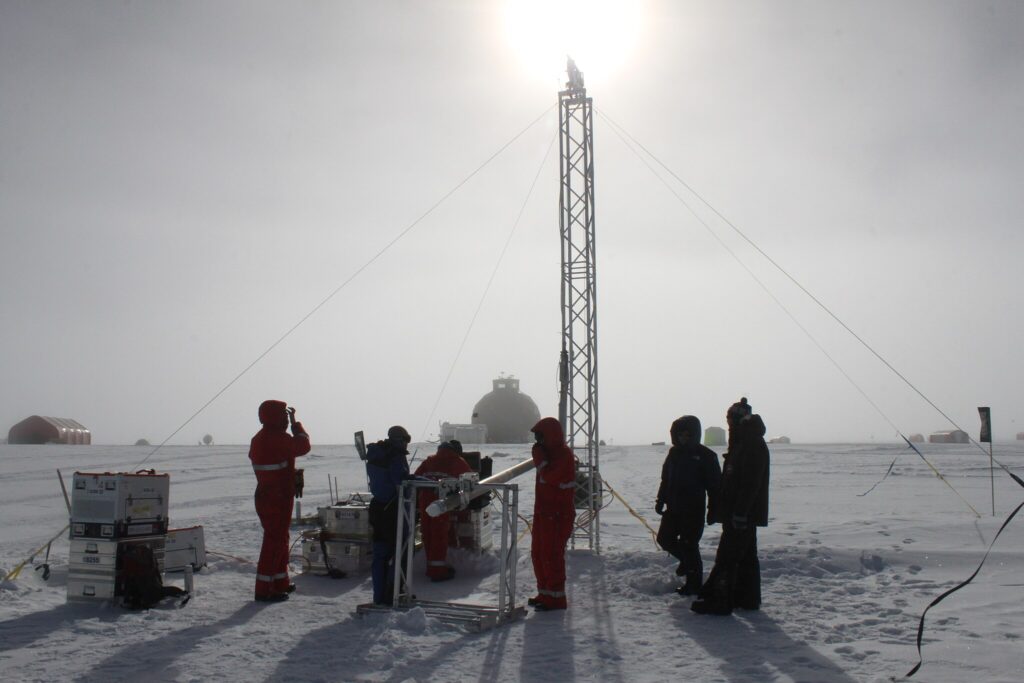

7. Scientists are expanding surveillance rather than raising alarms.

Research teams studying permafrost viruses emphasize preparation over fear. Their work focuses on cataloging what exists, testing survivability, and mapping potential exposure routes. This proactive approach mirrors how scientists track emerging diseases worldwide.

Rather than reacting to a crisis, researchers are building baseline knowledge. Understanding ancient viruses improves models of viral persistence and evolution. It also strengthens global readiness by identifying which traits allow long term survival, information that applies equally to modern pathogens circulating today.

8. Climate change drives the real risk behind discoveries.

The virus itself is not the primary threat. The larger issue is the warming that exposes it. As Arctic temperatures rise faster than the global average, permafrost thaws deeper and more often. Each thaw event releases stored carbon, microbes, and unknown biological material.

This cascading effect links climate systems with biological ones. The discovery of ancient viruses becomes another indicator of accelerating change. It highlights how warming unlocks processes humanity has never managed before, forcing science to operate in terrain that was once permanently frozen.

9. Public health systems already plan for unknown pathogens.

Global health agencies routinely model disease emergence from unexpected sources. Zoonotic spillover, laboratory accidents, and environmental shifts are all considered. Ancient viruses now join that list as theoretical possibilities rather than immediate threats.

Preparedness relies on flexible surveillance, rapid diagnostics, and transparent data sharing. The systems designed for modern outbreaks are also suited for rare scenarios involving ancient microbes. That overlap offers reassurance. Even unfamiliar discoveries fit within frameworks already built to handle uncertainty.

10. Curiosity matters as much as caution going forward.

These discoveries reshape how people think about time, biology, and climate. A virus surviving twenty thousand years challenges assumptions about fragility and permanence. It invites deeper questions about what else lies preserved beneath ice.

Approaching the subject with curiosity keeps fear in check. Scientists continue studying ancient viruses not because disaster is imminent, but because understanding the past sharpens readiness for the future. Awareness, not worry, becomes the most useful response as the ice continues to change.