A distant galaxy is breaking the expected timeline.

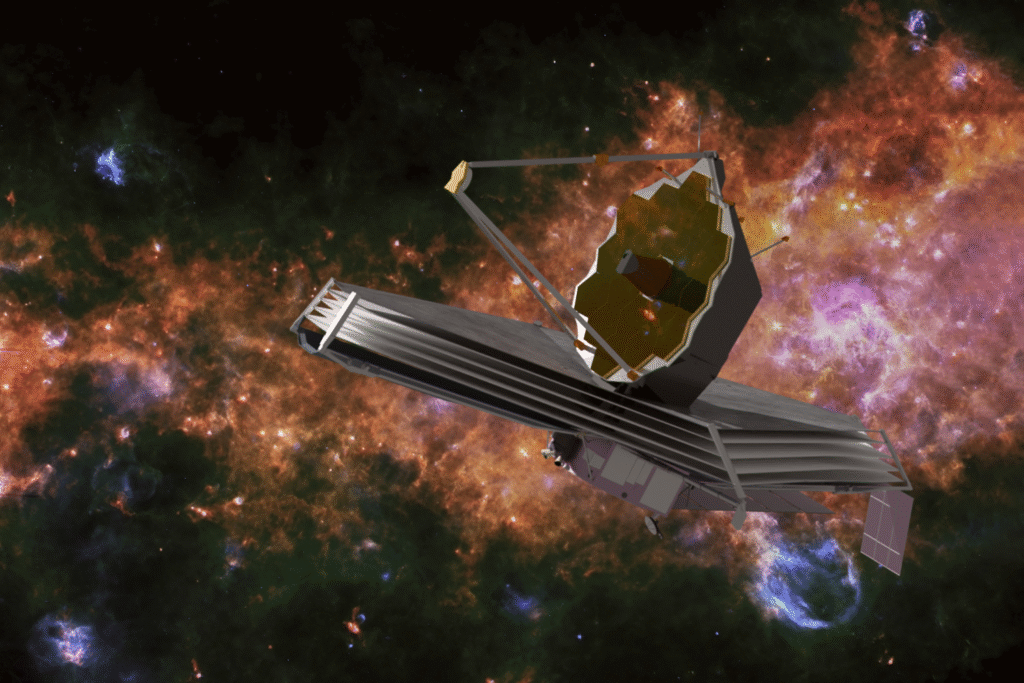

A faint galaxy spotted by the James Webb Space Telescope has turned into a serious challenge for astronomers studying the early universe. The object formed just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, yet it already shows signs of chemical maturity that should have taken far longer to develop. That mismatch between age and development is pushing NASA scientists to reconsider how fast early galaxies grew, how quickly stars enriched their surroundings, and whether the first chapters of galaxy formation unfolded far more rapidly than models have assumed.

1. One Webb galaxy appears unusually evolved.’

The discovery began with a small but unusually bright galaxy identified in deep field observations from the James Webb Space Telescope. Its light traveled across more than thirteen billion years of space, meaning astronomers are seeing it as it existed when the universe was extremely young. At that stage, galaxies are expected to be small, irregular, and chemically primitive. This one did not fit that picture.

Spectroscopic measurements revealed strong emission features that confirmed its extreme distance and intrinsic brightness. That brightness alone suggested vigorous star formation was already underway. According to NASA, the observation required extended exposure time to verify the galaxy’s redshift with high confidence. Once confirmed, the object immediately stood out as something that should not look so developed so early, triggering deeper analysis across multiple observatories.

2. Oxygen was detected far earlier than predicted.

After confirming the galaxy’s distance, researchers focused on its chemical composition. The real surprise came when oxygen was detected within the galaxy’s interstellar gas. Oxygen is produced inside stars and distributed through stellar winds and supernova explosions, which usually requires multiple generations of stars. Seeing it this early compresses the expected timeline of chemical enrichment.

The detection was made using observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter Array, which is sensitive to cold gas and specific emission lines invisible to Webb. According to the European Southern Observatory, the oxygen signal was clear enough to rule out contamination from closer objects. This finding implies that stars formed, evolved, and enriched the surrounding gas far faster than standard models predict for galaxies at this stage of cosmic history.

3. Independent instruments confirmed the galaxy’s maturity.

One reason the discovery carries weight is that multiple instruments contributed complementary evidence. Webb provided precise distance measurements and insight into stellar light, while ALMA independently confirmed both the galaxy’s redshift and its chemical content through gas emissions. That agreement reduces uncertainty and strengthens the case that the galaxy is genuinely mature rather than misidentified.

The oxygen emission also showed internal gas motion consistent with a structured system rather than a loosely assembled cloud. As reported by the ALMA Observatory, this convergence of data makes it difficult to explain the galaxy as an anomaly caused by observational error. Instead, it suggests a real physical process that allowed early galaxies to evolve faster and more efficiently than long held theories allow.

4. Star formation likely began earlier than assumed.

To account for the observed oxygen, star formation must have started significantly earlier than the moment we are observing. Massive stars burn quickly and enrich their surroundings within a few million years, but producing measurable oxygen still requires intense early activity. This suggests that star formation ignited almost immediately after the first gas collapsed into a galaxy.

That realization pushes theorists to consider scenarios where cooling and collapse happened faster in certain regions of the early universe. Dense pockets of gas, rapid inflows along cosmic filaments, or unusually efficient cooling mechanisms may have allowed stars to form without long delays. NASA researchers are now testing models that allow for earlier ignition rather than gradual buildup.

5. Chemical recycling happened at extreme speed.

Detecting oxygen is not just about making heavy elements. Those elements must also be mixed into surrounding gas to become visible in observations. That mixing requires turbulence, feedback, and circulation within the galaxy, processes that were thought to take longer to become effective.

This galaxy appears to have completed that cycle rapidly. Stars formed, produced oxygen, and redistributed it throughout the interstellar medium without halting further star formation. That balance is difficult to maintain even in mature galaxies. Its presence here suggests early systems may have been better at regulating feedback than models currently assume, allowing enrichment without shutting themselves down.

6. Dust formation may have followed quickly.

Where heavy elements exist, dust often follows. Dust grains form from elements like oxygen, carbon, and silicon, and they play a critical role in cooling gas and enabling new star formation. Many early universe models assumed dust would be rare at very high redshift due to limited time for grain production.

This discovery weakens that assumption. If oxygen is already present, dust formation may have begun earlier than expected as well. Dust can obscure starlight, alter galaxy colors, and accelerate further collapse of gas clouds. Its early appearance would help explain why some young galaxies appear brighter and more complex than anticipated in Webb observations.

7. Early black hole growth becomes more plausible.

Rapid star formation and chemical enrichment also affect black hole growth. Dense gas environments provide fuel for black holes, and energetic feedback can help funnel material inward. If early galaxies matured quickly, the conditions needed to grow black holes may have been present far earlier than previously believed.

This aligns with other Webb observations hinting at surprisingly massive black holes in the early universe. The chemically evolved galaxy supports the idea that early systems were not too primitive to sustain black hole growth. Instead, they may have provided fertile environments where both stars and black holes grew together from the start.

8. Galaxy formation models face tighter constraints.

Simulations must now reproduce not just early brightness but early chemistry as well. Producing a luminous galaxy is easier than producing one that also shows mature chemical signatures without breaking other observational constraints. Models must explain how gas cooled, stars formed, metals spread, and feedback remained balanced.

This forces theorists to revisit assumptions about star formation efficiency, feedback strength, and the initial mass distribution of early stars. The galaxy acts as a demanding benchmark. Any successful model must account for its properties without overproducing similar objects elsewhere in the universe.

9. Future observations will test whether it is typical.

Astronomers are now searching for similar galaxies to determine whether this object is rare or representative. Webb will continue spectroscopic surveys, while ALMA will probe additional chemical lines and dust emission. Finding more examples would confirm that rapid early evolution was common rather than exceptional.

If such galaxies are widespread, it would suggest the early universe matured in fits and starts rather than gradually. If they remain rare, they may highlight special conditions that existed only in certain regions. Either outcome will refine how NASA interprets early galaxy surveys moving forward.

10. Early galaxy growth may have occurred in bursts.

One emerging explanation is that early galaxies grew in intense bursts rather than steady progression. Rapid gas inflows or early mergers could trigger brief periods of extreme star formation, producing quick chemical enrichment before activity slowed again.

This burst driven view allows galaxies to appear surprisingly mature at young ages without rewriting all of cosmic history. It suggests the early universe was uneven, with some regions racing ahead while others lagged. For NASA scientists, this discovery does not overturn galaxy formation theory, but it reshapes its early chapters, revealing a universe that may have evolved faster and less smoothly than once believed.