A colossal freshwater dolphin emerges from the past.

Paleontologists have uncovered the skull of a newly described river dolphin species in the Peruvian Amazon, believed to have swum those waters around 16 million years ago. The creature, named Pebanista yacuruna, is considered the largest known freshwater dolphin ever found, measuring between 3 and 3.5 meters in length. The surprise is that it’s more closely related to South Asian river dolphins than to modern Amazonian ones, suggesting a long and unexpected evolutionary path.

1. The fossil was found along the Napo River in Peru.

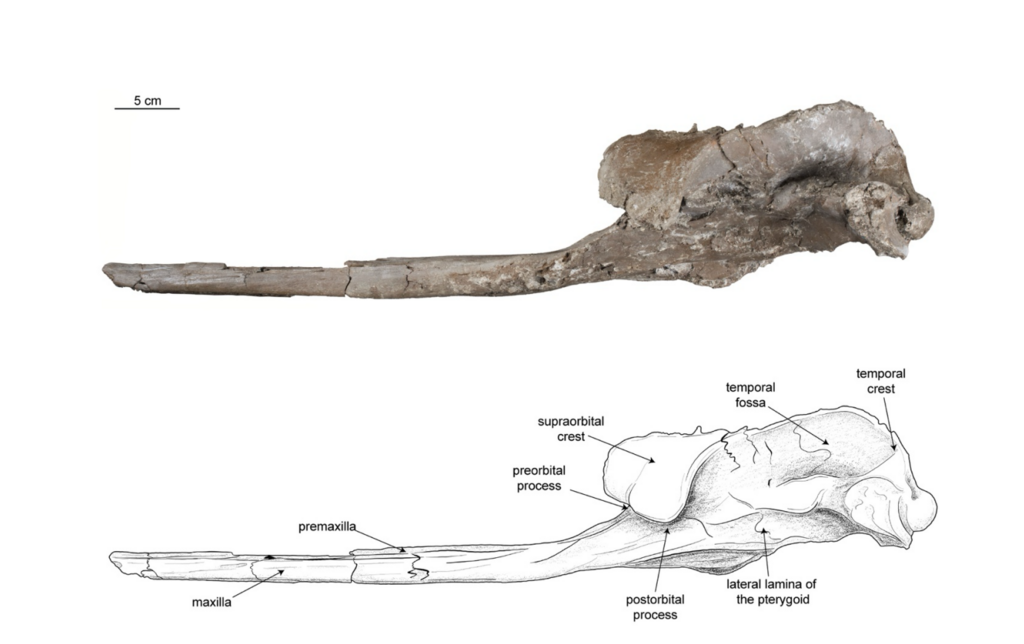

During an expedition along the remote banks of the Napo River, researchers located a fossilized skull embedded in sedimentary rock structures. The skull had been exposed by erosion during low river levels, providing a rare window into ancient river systems. According to press reports by Mongabay, what first appeared to be a large reptile jaw soon revealed distinctive dolphin tooth sockets.

That initial fossil sparked broader excavation, leading to discovery of additional fragments—mandible, skull roofing, and dentition. Together they confirmed a previously unknown river dolphin species.

2. The new species is called Pebanista yacuruna.

Scientists honored local myth by naming the species after the “Yacuruna,” legendary aquatic beings in indigenous Amazonian lore, while combining it with Pebas, referencing the ancient wetland system it inhabited. The name Pebanista yacuruna thus reflects both its ecological origin and cultural significance, according to the researchers who described it.

The formal description places it in an extinct genus of freshwater odontocetes with unexpected biogeographic ties. Naming it this way helps link paleontology and local heritage.

3. It is estimated at about 3 to 3.5 meters long.

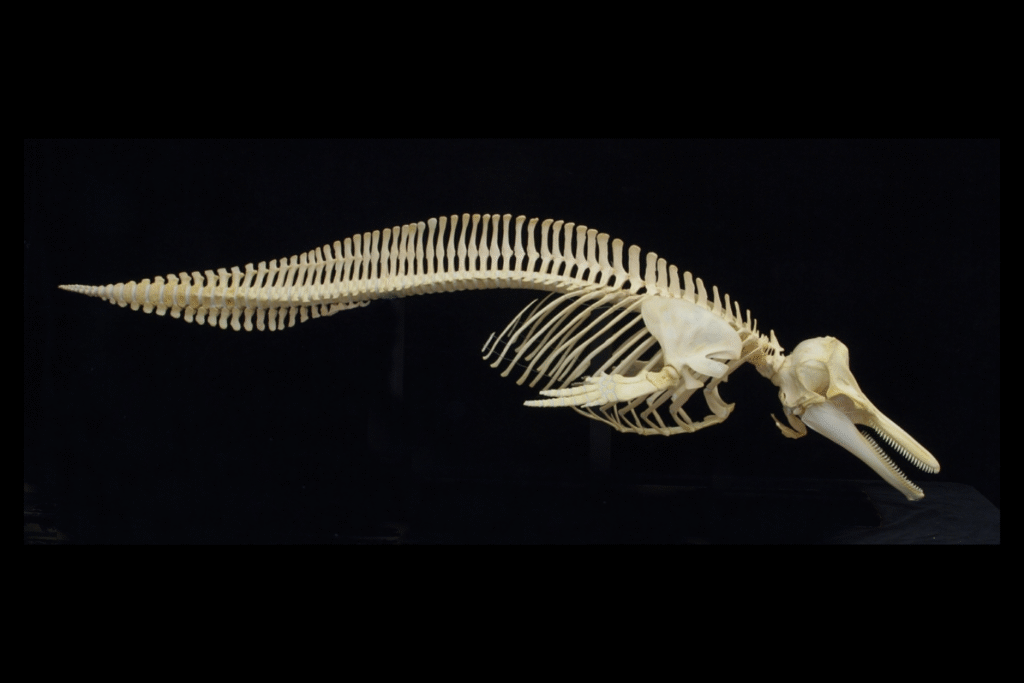

Based on skull proportions and comparative anatomy, scientists estimate Pebanista yacuruna measured roughly 3 to 3.5 meters in length—about 9.8 to 11.5 feet. That scale makes it larger than any modern river dolphin. The team’s assessment, as reported in the study and media summaries, cites this size as making it the biggest freshwater dolphin known.

Its long, toothed snout and robust bone structures support that estimate. The body plan likely included muscle attachments suited for riverine navigation and prey capture.

4. Its closest relatives live in South Asia today.

Contrary to expectations, Pebanista yacuruna shares a closer evolutionary relationship with the river dolphins of South Asia (the genus Platanista) than with the Amazon’s own pink river dolphin. This suggests a surprising historical connection across vast geographic distance.

This relationship implies that ancestors of this dolphin group invaded river systems independently, and that lineages diverged long ago. The discovery challenges assumptions about how river dolphins dispersed and evolved worldwide.

5. It lived during the Miocene epoch, sixteen million years ago.

The fossil is dated to approximately 16 million years ago, during the mid-Miocene period, a time when the Amazon basin’s landscape was dominated by wetlands, lakes, and rivers rather than the modern mega-river. That era, known as the Pebas system, provided the aquatic habitat for Pebanista yacuruna.

As the landscape transformed, large wetlands gave way to more confined river channels. That transition likely reduced habitat for large river specialists, contributing to the eventual extinction of this giant dolphin.

6. It used echolocation aided by facial bone crests.

The skull exhibits well-developed cranial crests over the melon region, structures believed to focus sound and assist in echolocation. Muddy water in river systems limits vision, so biosonar is critical. Pebanista yacuruna likely relied heavily on acoustic navigation and prey detection in turbid freshwater channels.

Those crests connect it to modern echolocating river dolphins, reinforcing functional similarities despite different lineages. The design suggests strong sensory adaptation to a life in low-visibility water.

7. Its prey likely included fish in ancient rivers.

With a long, toothed snout and robust jaws, Pebanista yacuruna probably hunted fish in the Miocene river system. Its dental pattern suggests a diet of sizeable prey, not tiny invertebrates. It functioned as a higher-order predator in its ecosystem.

Its size would have allowed it to take larger fish that smaller dolphins could not, helping it occupy a niche with fewer competitors. Over time, shifts in prey availability would have pressured its survival.

8. Its extinction was tied to habitat shift and prey loss.

As the Amazon basin’s hydrology changed approximately 10 million years ago, the massive wetlands of the Pebas system contracted. Many fish species vanished or migrated, shrinking the ecosystem that sustained Pebanista yacuruna. As the habitat narrowed, the giant dolphin’s specialized niche collapsed.

That collapse likely opened space for other lineages—such as ancestors of modern Amazon river dolphins—to evolve in the resulting riverine environment. The extinction highlights how landscape transformation can erase even large and well-adapted species.