Researchers say the behavior may reflect mounting pressure.

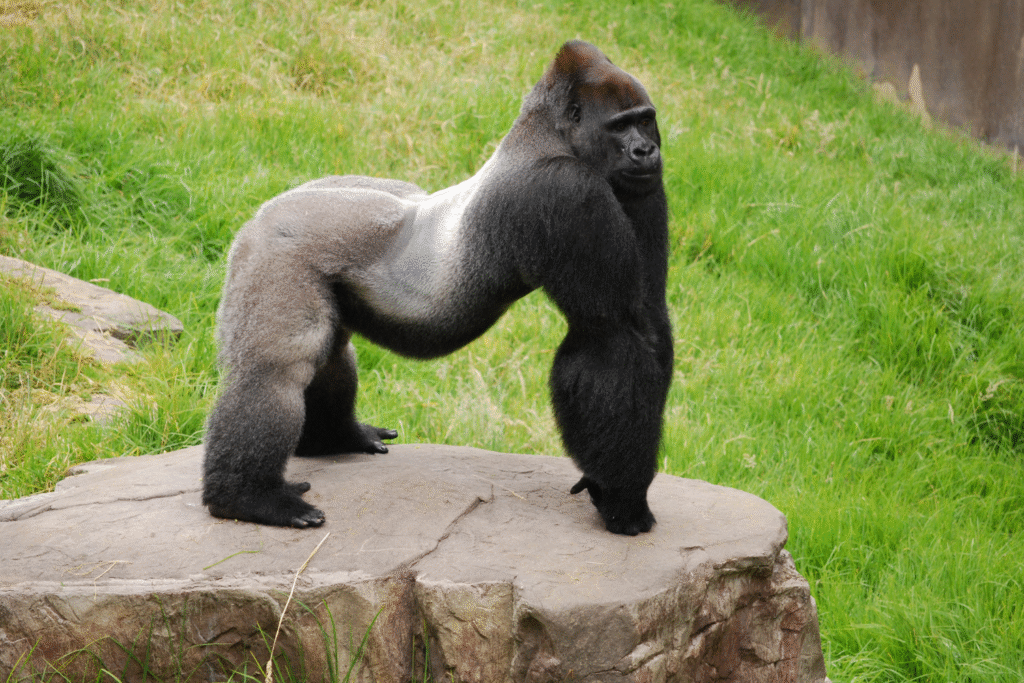

For decades, gorilla societies followed patterns that felt tragically predictable but stable. That stability is now starting to fracture. A new body of research points to a rise in infant killings within some gorilla groups, a behavior scientists once considered rare and situational. The most unsettling part is not the violence itself, but the conditions surrounding it. As habitats shift and food becomes less reliable, researchers are asking whether environmental stress is beginning to rewrite behaviors long thought to be fixed.

1. New males entering groups often trigger infant deaths.

When a silverback is displaced, infants that are not his offspring usually don’t survive the transition. As discovered by the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund, this isn’t random cruelty but an evolutionary strategy to restart female fertility faster. Yet, researchers note that in fragmented habitats made worse by climate change, silverbacks face greater risks of injury, displacement, and death. That instability means more takeovers, and more infants at risk. The cycle, once occasional, appears to be intensifying in landscapes where warming temperatures are already thinning forest cover.

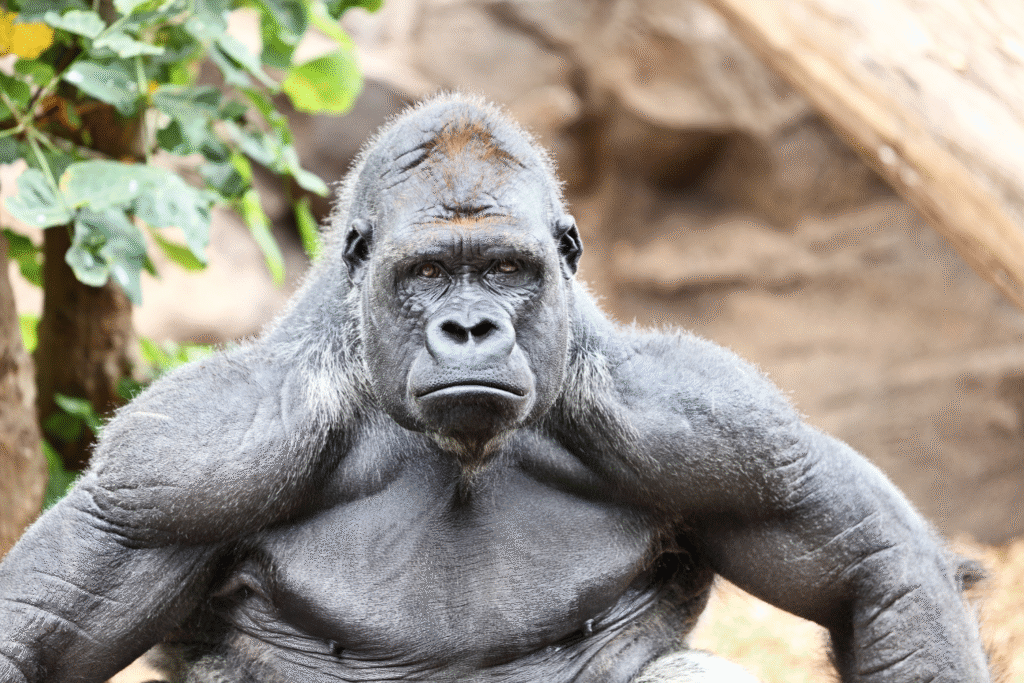

2. Stress from habitat loss is making aggression worse.

Forests are no longer reliable sanctuaries. Expanding farmland, mining, and logging are leaving gorillas stranded in smaller ranges. As stated by a study in Conservation Biology, deforestation drives infanticide higher. Climate stress piles onto this, as hotter, drier conditions fuel crop expansion deeper into gorilla territory. More clashes for territory mean more dominance fights, and each power shift puts infants in danger. A single bulldozer or burned field might seem distant from gorilla life, but the chain reaction often ends with newborns caught in the middle.

3. Orphaned infants often fall to rival males.

When poachers kill silverbacks, rivals quickly take over and infants are targeted. As reported by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, this outcome is common in regions with intense hunting. Climate change worsens it by driving human communities deeper into forests in search of farmland and food, which escalates hunting pressure. Without strong leaders, gorilla families collapse, and infants are left vulnerable. The connection may not be obvious at first glance, but the ripple effects of warming temperatures reach even the smallest, most fragile members.

4. Females sometimes risk everything to resist infanticide.

Mothers often fight until their last breath to protect their infants, with some even leaving their groups in desperate attempts to save them. Conservationists note that climate-linked instability is straining maternal defenses. With scarcer food and longer travel to find it, females are often weakened, making their resistance less successful. Still, their determination highlights just how much is at stake. Every infant represents years of investment in a species with one of the slowest reproductive rates on Earth, making each loss even harder to absorb.

5. Younger males can become unexpected threats to infants.

The stresses of climate change do not only disrupt dominant males. Subordinates, often blocked from reproducing, sometimes lash out at infants in moments of tension. Scientists suspect resource scarcity may be amplifying frustration, as younger males struggle to secure status in groups stressed by shifting conditions. These incidents destabilize families from within, sparking fear and mistrust among females. It’s another reminder of how rising global temperatures can twist even small social cracks into violent consequences for the youngest gorillas.

6. Human observers have recorded more incidents than ever.

Researchers in Rwanda and Uganda now track infanticide cases at rates higher than decades past. While better monitoring plays a role, many point to ecological pressures as a driving factor. Hotter weather disrupts fruiting cycles and alters food distribution, leading groups into more frequent conflict. In a world where gorilla numbers are already dangerously low, every new report feels like a warning. Behind the data sheets and field notes lies a grim reality: climate instability is pushing violence deeper into the social fabric of gorilla life.

7. Infanticide is not unique to gorillas but stands out.

Primates like langurs and chimpanzees also kill infants, yet gorillas stand apart because of their reproductive pace. A female may only raise a handful of infants across her lifetime. Climate change compounds the risk because environmental shocks create conditions where takeovers and aggression spike more often. Each infant lost carries the weight of decades, not years, of recovery. That slow rhythm makes gorilla infanticide, already devastating, far more consequential in a warming world where every birth matters.

8. Conservationists fear cycles of violence are hard to break.

Infanticide destabilizes groups for years, and climate stress threatens to lock gorillas into repeating cycles of loss. As habitats shrink and temperatures climb, females may roam further in search of protection, sparking new rivalries and exposing more infants to risk. Conservationists argue that without stronger habitat protections, the violence may not only continue but accelerate. The frightening part is that climate change doesn’t just shrink forests; it reshapes social behaviors, turning families against themselves in ways rarely seen before.

9. Infants that survive often carry lifelong scars.

The emotional toll runs deeper than physical survival. Young gorillas that witness infanticide often develop withdrawn behaviors, while mothers have been seen carrying the bodies of lost infants for days. Climate-driven stress magnifies this trauma, as mothers already exhausted by food scarcity and heat must cope with grief. These are not just isolated tragedies but events that echo across generations. The invisible scars become part of the group’s story, shaping how survivors interact and rebuild after violence.

10. Scientists warn rising cases could alter future evolution.

If climate change continues to fuel instability, gorillas may adapt in unexpected ways. Some researchers speculate that females could increasingly align with protective males, while others fear reduced genetic diversity if dominant males control breeding under harsher conditions. The truth is we may be witnessing evolutionary shifts born of a crisis we helped create. Climate change is no longer just a backdrop—it is rewriting the survival script of one of humanity’s closest relatives, starting with the most vulnerable lives in their groups.