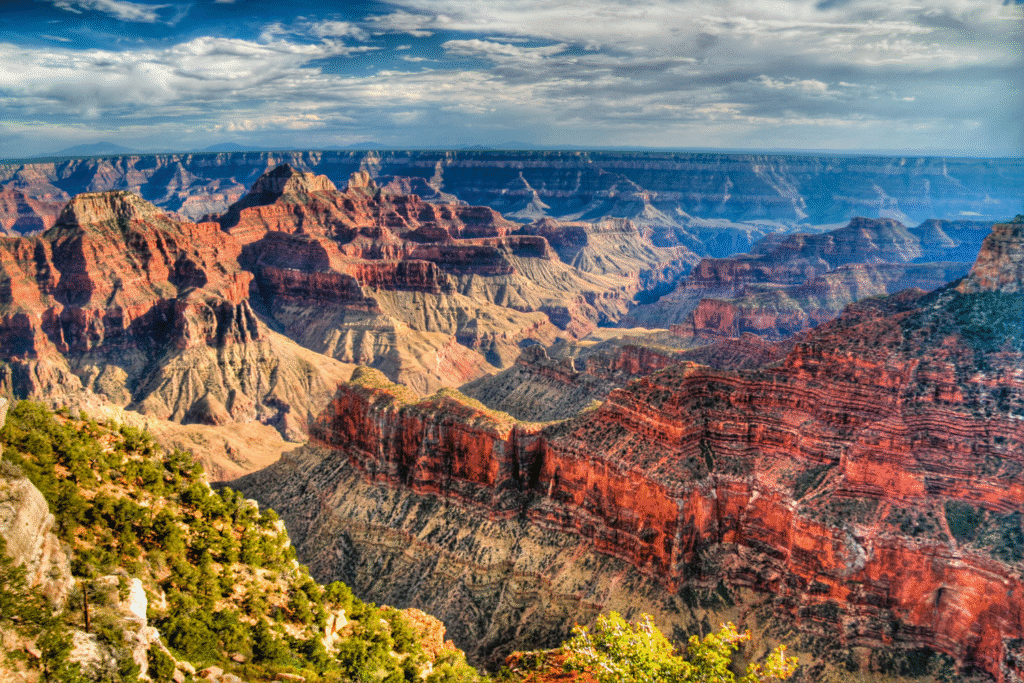

An astonishing discovery hidden in canyon shadows.

The story starts with a rumor that refuses to die. More than a century ago, an Arizona newspaper claimed explorers had stumbled upon something incredible inside the Grand Canyon—ancient chambers filled with relics, carvings, and mummies unlike anything seen in North America. The Smithsonian reportedly denied it, calling the story a myth. But recently, a ranger working deep inside the canyon said he uncovered evidence that eerily matched those long-dismissed accounts. Now, whispers are turning into questions about whether one of America’s most protected landscapes has been hiding a century-old secret after all.

1. The original 1909 newspaper detailed strange cave findings.

In April 1909, the Arizona Gazette published a detailed story about explorer G. E. Kincaid, who allegedly discovered a vast underground complex inside the Grand Canyon. The article described rooms filled with copper weapons, carved figures resembling Egyptian gods, and mummified remains. The supposed entrance sat high on a sheer cliff wall, far from any known settlement. While the story was widely shared at the time, no expedition ever confirmed its claims. Still, the details remain curiously consistent with some geological features nearby, according to the National Park Service archives and historical references from the Arizona Gazette itself.

2. The Smithsonian denied any records of the expedition.

When journalists and researchers tried to trace the story, the Smithsonian Institution stated it had no record of G. E. Kincaid, Professor S. A. Jordan, or any related expedition. The institution emphasized that its anthropologists never conducted fieldwork in the described area. This denial, as stated by Smithsonian archivists, effectively labeled the 1909 report as fiction. Yet over the decades, the Smithsonian’s rebuttal only seemed to amplify public fascination. To some, that silence hinted at something hidden in plain sight. To others, it simply underscored the need for verifiable evidence before reshaping history, as documented by the Smithsonian’s official response.

3. A modern ranger reports discovering an opening consistent with the legend.

In 2024, a Grand Canyon ranger—choosing anonymity for professional protection—claimed he stumbled upon an unusual opening halfway up a remote section of Marble Canyon. He described it as a smooth, oval-shaped entrance, unnaturally precise amid the rugged cliffs. Inside, he reportedly found carved walls and small alcoves containing weathered stone statues, resembling figures from Old World iconography. The story, reported by Survival World, recounts how he recorded coordinates and later shared them with superiors, who allegedly sealed the area pending investigation. That revelation reignited online debate, bridging folklore and modern discovery in an unexpectedly thrilling twist of fate.

4. The location lies in a restricted zone of the canyon.

The ranger’s description placed the site within one of the canyon’s restricted scientific zones, areas closed to public entry due to safety and preservation concerns. These regions, controlled by the National Park Service, are rarely accessed without special permits. Such limits add credibility to the ranger’s claim since most hikers could not reach those heights even with modern equipment. Yet those same boundaries now block independent confirmation. This paradox—where preservation prevents verification—has kept speculation alive, allowing mystery to coexist with regulation in a way that keeps the story hovering between possibility and folklore.

5. The artifacts described challenge established archaeology.

If the ranger’s account proves accurate, it could challenge accepted archaeological timelines for the American Southwest. The reported objects—metal tools, hieroglyph-like carvings, and sarcophagus shapes—do not align with the known cultural history of the region’s Indigenous peoples. Archaeologists suggest such claims demand extraordinary proof, including carbon dating and material sourcing. Still, the idea that transoceanic travelers might have reached North America thousands of years ago has been debated for decades. The difference now lies in alleged physical evidence, which, if authenticated, could redefine how civilizations interacted long before recorded history connected their worlds.

6. The story has strong elements of legend and hoax.

Historians and journalists examining the original Arizona Gazette story point out that it fits neatly into the era’s fascination with lost civilizations and sensational discoveries. Early 20th-century papers often exaggerated or invented accounts to attract readers, and the absence of follow-up coverage fuels skepticism. Experts have found no archival record of Kincaid or Jordan beyond that one article, suggesting a possible fabrication. Yet, unlike most hoaxes, this one persists across generations. The sheer endurance of the legend suggests it touches something deeper—a collective curiosity about what secrets ancient landscapes might still conceal.

7. The ranger’s report lacks independent verification or chain of custody.

Modern science depends on verification, and this story offers none so far. The ranger reportedly submitted his findings to supervisors, but no official photos, coordinates, or artifacts have surfaced. Without peer review or third-party corroboration, his claim remains speculation. Some suggest the government may be withholding information for preservation or security reasons, but those ideas lean more into conspiracy than scholarship. Others think it may all stem from misinterpretation or storytelling fatigue from long patrols in isolation. Until verifiable data emerges, the account sits somewhere between confession and campfire tale.

8. There are potential explanations other than advanced ancient civilization.

Geologists who’ve examined the canyon note that nature can sculpt surprisingly geometric features, especially where volcanic basalt and sediment meet. Shadows and erosion can mimic human handiwork. Anthropologists add that Indigenous rock art and ceremonial sites sometimes carry symbolism mistaken for other cultural origins. These perspectives don’t erase the mystery but ground it in science. It’s possible the ranger’s observations reflect natural geology or cultural layers already known but misread under pressure. Even if debunked, the claim still invites renewed curiosity about how myths evolve around real landscapes and enduring human fascination.

9. The public interest is growing because of parallels to conspiracy themes.

In the digital age, stories mixing archaeology with secrecy spread fast. The notion that powerful institutions might hide ancient discoveries resonates with online communities eager to challenge official narratives. Videos, podcasts, and social media threads have amplified this Grand Canyon legend again, giving it a second life. It’s no longer about one explorer or one ranger—it’s about the tension between discovery and authority. That emotional core keeps audiences hooked, not for proof of mummies in caves, but for the possibility that truth sometimes hides behind bureaucracy and disbelief.

10. Real proof requires independent research, transparency and collaboration.

For this mystery to move beyond speculation, it will take collaboration between archaeologists, geologists, Indigenous leaders, and the National Park Service. Only transparent, documented fieldwork can confirm or dismiss the ranger’s claim. Such an effort would need to respect cultural sensitivities and environmental laws while allowing open scientific scrutiny. If evidence exists, it should be analyzed, not concealed. If it doesn’t, then debunking it would finally free the legend from shadow. Either way, the canyon will keep its quiet dignity—its cliffs unchanged, its mysteries waiting for those patient enough to seek truth.