Drought reveals rare Hellenistic era cemetery in northern Iraq.

A remarkable discovery has surfaced in the Khanke region of northern Iraq where water levels at the Mosul Dam reservoir dropped enough to expose a cemetery dating back roughly 2,300 years. The tombs appear connected to Hellenistic era settlement in the region and contain ceramic coffins, human remains and an array of offerings that reflect cultural exchange between Greek and local traditions. Researchers examining the site note that the material record is unusually well preserved, allowing a more precise look at burial practice, family continuity and ritual behaviour. What emerges is a richer understanding of how ancient communities negotiated identity in a changing world.

1. The cemetery resurfaced after significant drought reduced the reservoir.

Water recession at the Mosul Dam revealed a long submerged portion of terrain that had covered dozens of ancient graves. As the shoreline retreated, ceramic coffins and grave outlines became visible, prompting an immediate survey. According to Iraq’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage, more than forty graves emerged in the Khanke area. The exposure, while tied to environmental strain, created a rare opportunity to examine a Hellenistic era burial ground largely untouched by modern disturbance. This intersection of climate impact and archaeological access has reshaped how scholars consider water dependent sites and the fragile histories preserved beneath them.

2. The burial contents indicate long term use by extended families.

Clusters of coffins, repeated interments and varied offerings suggest that these tombs served multiple generations rather than single individuals. Ceramic containers, metal objects and organic remains show that relatives returned to the same plots for many years, creating a funerary landscape shaped by lineage. This pattern aligns with ritual continuity and reflects the social structures of the time, as reported by the Duhok Directorate of Antiquities. The emphasis on family connection is evident in the spatial arrangements and shared goods, offering a deeper look at how communities expressed belonging, continuity and remembrance within a single mortuary setting.

3. Cultural blending is evident in the objects and tomb architecture.

Researchers examining the material culture describe a notable mixture of Hellenistic and local Mesopotamian influences. As discovered by archaeologists documenting the Khanke site, Greek style ceramics appear alongside regionally produced vessels, while burial positions echo both imported customs and local traditions. This combination reflects selective adoption rather than complete cultural replacement. The tombs illustrate how ancient families navigated identity by integrating external ideas into familiar frameworks. These blended patterns expand discussions about cultural contact zones, suggesting that influence was negotiated at the household level and not imposed uniformly across communities.

4. The layout of the graves challenges earlier assumptions about hierarchy.

Instead of rigid stratification, the site reveals a cemetery organized by kinship rather than formal status markers. The consistent spacing and parallel arrangement of tombs imply shared norms across families, not a hierarchy imposed by elites. Offerings vary in type but not dramatically in scale, indicating broad access to goods. This distribution challenges interpretations that burial wealth alone defined social rank in Hellenistic Mesopotamia. Instead, continuity, ritual practice and family identity appear to have shaped the mortuary landscape more strongly than elite display. These findings prompt a reconsideration of how social role was expressed in regional funerary culture.

5. Preservation conditions show both advantages and new risks.

Being submerged for decades allowed some fragile materials to survive, including traces of textile, plant matter and vessel residues. However, sudden exposure introduces risks such as drying, cracking and microbial change. Conservation teams must now stabilise the remains quickly to prevent loss. The site illustrates a growing global challenge: climate driven water shifts can expose heritage unexpectedly while simultaneously accelerating its decay. In this case, preservation requires balancing rapid documentation with careful treatment, reinforcing the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in managing newly exposed archaeological landscapes.

6. Organic remains are offering insight into daily life and ritual.

Analysis of plant fragments, food residues and textile fibres recovered from the tombs is helping researchers rebuild aspects of diet, trade and ceremonial practice. Such remains are rarely preserved in open air cemeteries and therefore provide unusual detail. These materials help reconstruct what families valued during burial, how they interacted with agricultural environments and what foods carried symbolic meaning. They also illuminate economic patterns, such as trade links indicated by imported plant types. As laboratory results accumulate, they will refine broader interpretations of life and ritual in communities experiencing both Greek contact and local continuity.

7. Burial orientation may reflect shared cosmological views.

The consistent alignment of graves suggests that the community followed a structured mortuary system tied to belief or cosmology. Orientation patterns can reflect ritual directionality, symbolic protection or links to seasonal cycles. Scholars studying the spatial arrangement note that both adults and children follow similar directional logic, implying standardised practice across generations. This consistency deepens the argument that burial played a central role in expressing community identity. Mapping these alignments helps researchers connect physical arrangement to underlying worldviews that shaped daily life in Hellenistic influenced northern Mesopotamia.

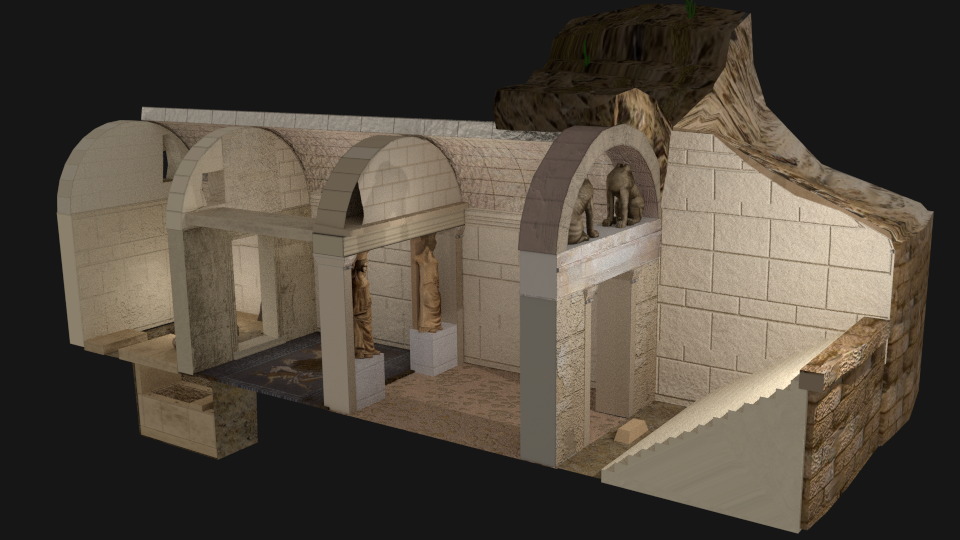

8. Architectural features suggest planned use rather than ad hoc burial.

Many tombs share construction techniques, spatial grouping and access patterns that indicate coordinated planning. Rather than spontaneous or scattered interments, the cemetery appears to have been designed for long term use. The durability of the ceramic coffins and the careful positioning of grave goods reflect thoughtful investment in funerary tradition. These patterns highlight the organisational capacity of the community and reveal how shared planning reinforced cultural identity. The cemetery thus serves as evidence of coordinated social practice that extended well beyond individual lifetimes.

9. The offerings reveal unexpected networks of trade and cultural mobility.

Some artefacts appear to come from regions far beyond northern Iraq, suggesting access to distant exchange routes. Variations in ceramic style, metalwork and decorative motifs indicate trade connections that challenge earlier assumptions about the isolation of inland settlements. These items imply movement not only of goods but also of ideas and skills. Such evidence broadens discussions of economic and cultural mobility during the Hellenistic period, demonstrating that communities like those in Khanke participated in wider regional and interregional interactions than previously assumed.

10. The tombs reshape understanding of identity in multicultural settings.

Taken together, the graves show that identity during this period was neither static nor unilateral. Families expressed themselves through selective adoption of Greek traditions while maintaining local customs, creating a layered cultural landscape. Offerings, architecture and interment patterns reflect a community negotiating influences with care rather than simply absorbing or rejecting them. The cemetery becomes a record of how everyday families integrated external ideas into personal and collective expression. This nuanced view enriches scholarship on cultural transformation and highlights the complexity of identity in regions shaped by overlapping traditions.