The ocean’s deep secret is not so quiet anymore.

We’ve grown used to the idea that the planet is heating up steadily, but now scientists are flagging a sneaky twist in the tale. In the chilly waters of the Southern Ocean, heat is building up, hidden beneath the surface, waiting for the right trigger. If circulation slows or winds change, that trapped warmth could release in a burst, altering climate recovery trajectories and surprising us in ways we might not expect.

1. Heat is accumulating in the Southern Ocean’s deep layers.

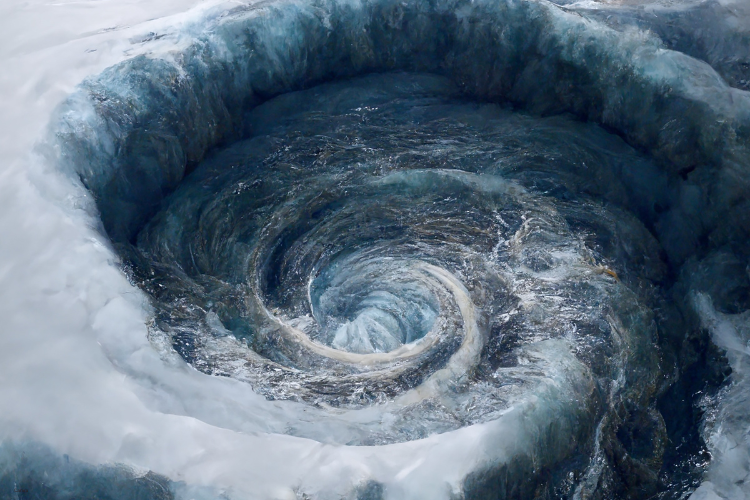

Researchers have found that the Southern Ocean is storing an extraordinary amount of heat in its deeper layers as warming continues. According to Earth.com, the ocean’s layered structure beneath the surface allows warmth to build up because stable stratification prevents efficient escape of that heat. In practical terms, that means the Southern Ocean is acting as a gigantic heat battery, and if the layers destabilize, the stored heat could be released. The implication is that even if surface warming slows, the ocean might surprise us with a rebound effect from below.

Flowing into the next point, this accumulation sets the stage for a potential “burp” of warmth, where the ocean lets loose decades of stored energy in a comparatively short time. That potential change is what climate scientists now worry about.

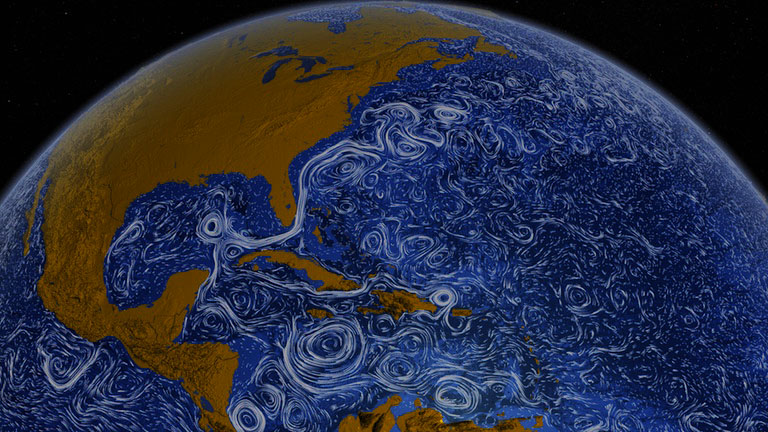

2. A slowdown of ocean circulation might trigger a rapid heat release.

Circulation patterns in the Southern Ocean play a critical role in regulating how heat and carbon are taken up and stored, as discovered by researchers exploring deep-ocean dynamics and interactions with the atmosphere. The study found that when these circulations weaken or change direction, the stored warmth beneath the surface layers could rise toward the surface and escape into the atmosphere, as reported by Yale Environment 360. In effect, a weaker overturning current or altered wind system could pull back the lid on decades of hidden heat. What looks like stabilization in surface temperatures might hide a ticking time-bomb of stored ocean energy.

Transitioning from the mechanism to its potential effect on the broader climate, the next point explores how this phenomenon could reshape our expectations for future warming and recovery.

3. The ocean’s delayed response complicates climate recovery timelines.

Because the ocean has a “memory” of past warming, the delayed release of heat complicates predictions of how quickly the planet might cool once emissions fall. In a simulation of negative emissions scenarios, the Southern Ocean was shown to release stored heat during the cooling phase, extending warming rather than allowing immediate recovery, as stated by Nature Climate Change. This means even if society reduces greenhouse gas emissions significantly, the surface temperature response may lag because the heat reservoir doesn’t follow instantly. The slower response complicates our imagination of a tidy return to cooler, stable conditions.

Shifting from the modeling to real-world components, let’s explore what other factors are layered into this scenario and how they reinforce the risk of a warming rebound.

4. Melting ice and fresh water input are weakening stratification.

As ice shelves and glaciers shed fresh water into the Southern Ocean, the density gradients change and stratification becomes more stable, meaning warm water gets trapped beneath a fresher surface layer. The newer input of freshwater makes the upper layer lighter, reducing mixing and isolating deeper warm layers. Because of this, the barrier between deep warm water and the atmosphere grows stronger, raising the odds of a later sudden release.

While the surface might seem calm and the deep water unchanging, the layering is quietly building pressure from below. That hidden buildup is what makes the “burp” scenario plausible rather than far-fetched.

5. Wind changes around the Antarctic region could alter upwelling dynamics.

Westerly winds and the circulation of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current help drive the upwelling of deep water and the exchange of heat between ocean layers. If climate change alters these winds such that upwelling weakens or shifts location, the trapped warm layers may become even more isolated or suddenly released. The modulation of these winds thus acts as a switch-point in the system.

In essence, the mechanism that has kept the deep layers stable is subject to change, and once that change occurs, the hidden warmth may move upward rapidly into the surface climate system.

6. The Southern Ocean drains most of the extra heat absorbed by the planet.

About 90 percent of the excess heat produced by global warming has been absorbed by the world’s oceans, and the Southern Ocean has been a major sink. Because of its vast reach and powerful currents, it quietly stored huge volumes of heat, delaying the full effect of warming in surface air temperatures. That storage has been a favor to the atmosphere but might now turn into a liability if the system destabilizes.

With so much heat locked away, the potential energy for a rapid release is far larger than we might intuitively expect. That puts the spotlight on the Southern Ocean’s role not just as passive storage but as a potential active driver.

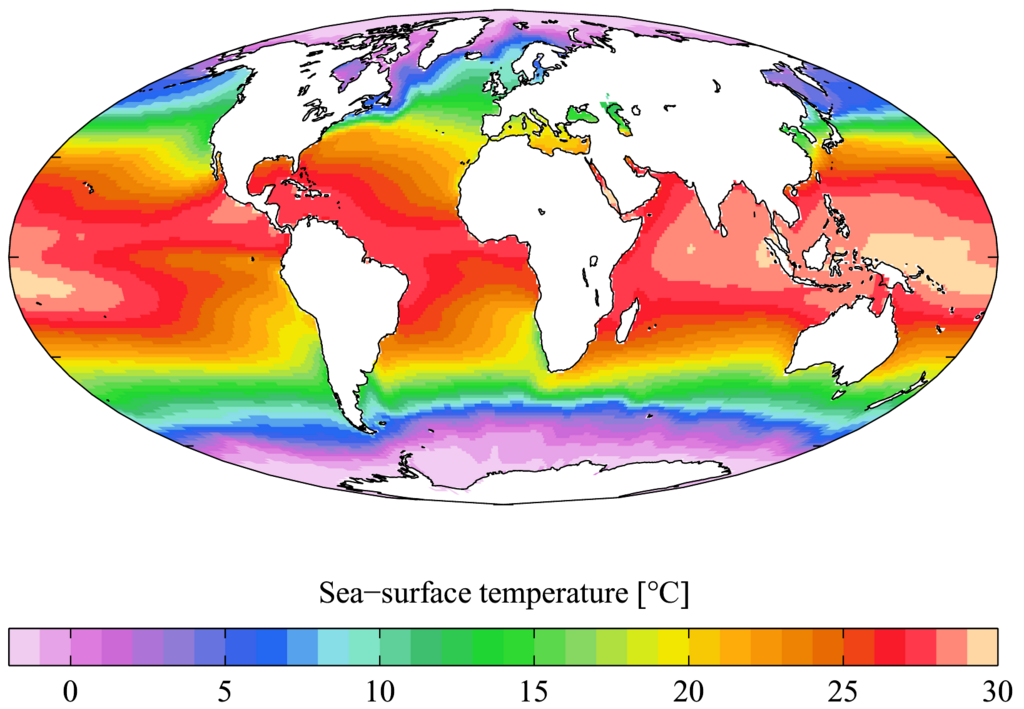

7. If release occurs, the thermal impact could be felt globally.

When deep-ocean heat finds its way to the surface, it doesn’t stay in one place. Surface warming then spreads via atmospheric and oceanic connections, meaning the consequences could ripple around the globe. Regions far from Antarctica could feel shifts in temperature regimes, sea-ice patterns, and weather extremes. The “burp” is not local; it’s planet-wide.

Because the ocean links so many systems—weather, ice, and currents—an abrupt release of trapped warmth could upset more than just the surface temperature trend.

8. Existing climate models may underestimate the risk of abrupt heat release.

Many models focus on gradual trends but may not fully capture the internal storage and potential abrupt release of ocean heat in the Southern Ocean. The emerging research suggests that current models need refinement in how they treat deep heat reservoirs, stratification changes, and circulation dynamics. Without these improved mechanisms, our forecasts for cooling or stabilization may be overly optimistic.

In other words, the timetable for climate recovery could be stretched significantly because of missing processes in our modeling frameworks.

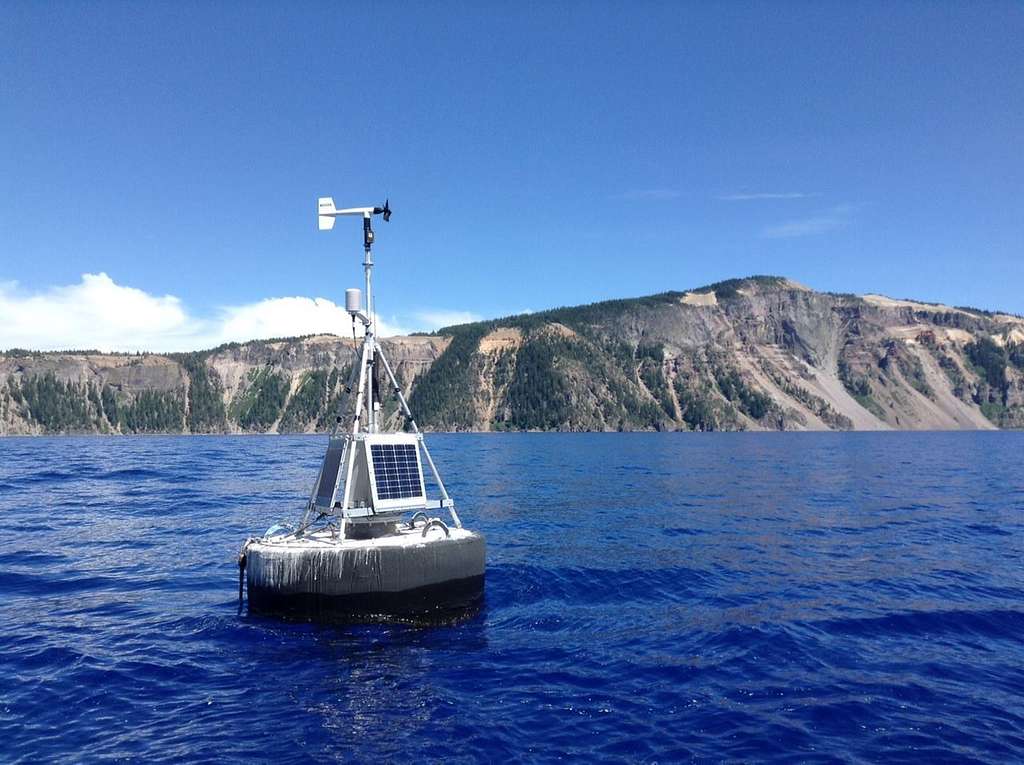

9. Monitoring deep-ocean temperature and circulation is increasingly urgent.

To better predict the timing and scale of any heat release, we need improved observations of the Southern Ocean’s depths, circulation, and layer dynamics. Measuring how heat is stored, and when it might escape, requires a network of sensors, floats, and modeling efforts focused on the hidden layers of the ocean. Better data is not just academic—it gives us a clearer view of risk and timing for surface climate shifts.

10. Policy and adaptation must account for hidden ocean heat risk.

Even as efforts focus on reducing emissions, policymakers and planners need to factor in the possibility of delayed recovery or renewed warming driven from the deep ocean. Adaptation strategies should reflect the fact that the ocean may hold surprises and that surface trends might mask underlying changes. It means we cannot assume that a drop in emissions equals immediate climate calm. The hidden ocean memory may disrupt that assumption.