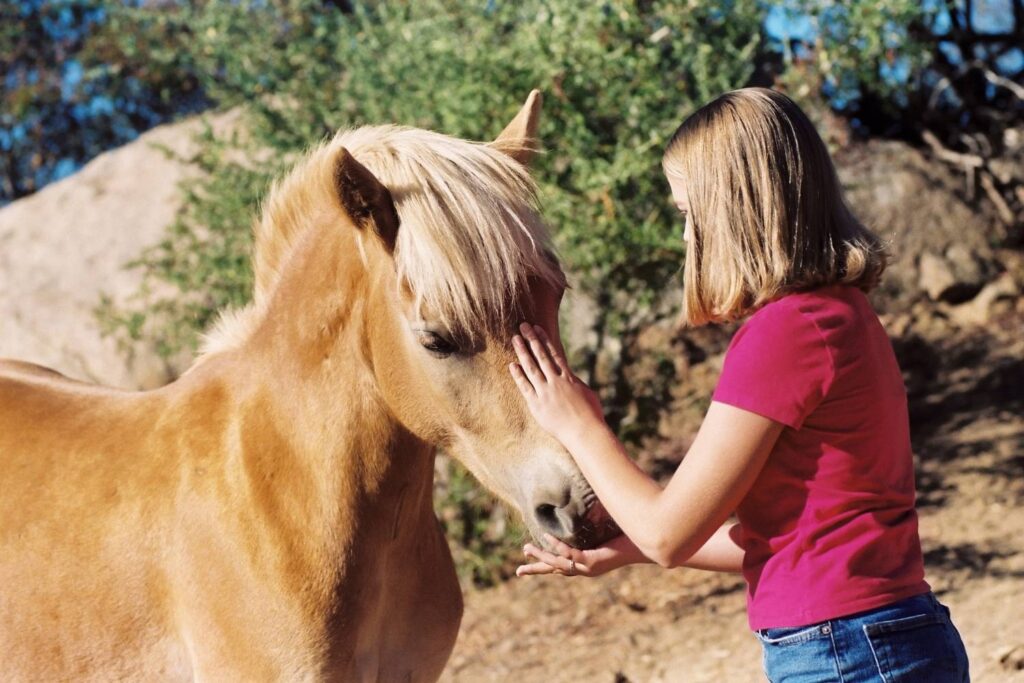

Attachment can quietly shift from trust to risk.

Horses are social animals shaped by group living and shared vigilance. When daily care narrows to one familiar person, attachment can deepen in ways that feel special yet carry hidden costs. Across barns, training facilities, and private properties, this pattern appears quietly. What looks like loyalty often masks rising stress, safety concerns, and long term behavioral fallout without warning or support.

1. Exclusive bonds can distort natural herd dynamics.

Horses evolved to distribute trust across a group, watching multiple bodies for safety cues. When one human replaces that network, vigilance narrows and anxiety rises. The horse scans constantly for a single presence, losing flexibility under pressure.

Behavior researchers observed this pattern in domestic horses showing separation stress during handling, according to the University of Lincoln, where equine social bonding studies linked exclusive attachments with heightened reactivity and reduced coping during routine disruptions across managed stables in recent years internationally.

2. A single handler can become a control anchor.

Daily feeding, grooming, and training handled by one person can shift boundaries. The horse begins to anticipate that person for movement, release, and reassurance. Others are ignored or resisted, creating imbalance during care routines.

This dependency increases risk during emergencies when that handler is absent. As stated by the British Horse Society, horses with narrow attachment patterns show delayed compliance and heightened agitation when unfamiliar staff intervene unexpectedly during transport, veterinary care, or sudden schedule changes within busy training facilities.

3. Over attachment increases separation stress and panic.

When the bonded person leaves, some horses display calling, pacing, sweating, or refusal to eat. These behaviors mirror herd separation responses. The stress can escalate quickly, especially in confined stalls or unfamiliar environments.

Physiological data supports this response. As reported by the American Association of Equine Practitioners, cortisol levels spike higher and remain elevated longer in horses experiencing human based separation stress compared to routine herd movements during clinical observations conducted in boarding barns across multiple regions over time periods.

4. Protective behavior may escalate toward other people.

Some horses begin blocking access, pinning ears, or crowding when others approach their bonded person. What starts as closeness shifts toward resource guarding. The horse attempts to manage proximity, a risky behavior around large animals.

This escalation raises safety concerns for handlers and visitors. Horses are powerful and fast. Without clear boundaries reinforced by multiple caregivers, protective responses can turn unpredictable during routine barn activities including farrier visits, lesson changes, and emergency handling situations where timing and coordination matter most.

5. Training progress can stall under narrow trust.

Horses learning from one person often perform well in familiar settings. Problems appear when cues come from someone else. The horse hesitates, resists, or shuts down, slowing overall development.

Balanced training requires generalization across handlers. Exposure to varied body language and timing builds adaptability. When trust is shared, learning transfers more reliably, reducing frustration for horses expected to work with trainers, grooms, and riders interchangeably across facilities, disciplines, and changing schedules over long careers without emotional collapse under pressure moments.

6. Illness or injury complicates exclusive bonding patterns.

Medical care often involves multiple professionals. A horse bonded to one person may resist examination or treatment by others. Stress rises during procedures, increasing risk for everyone involved.

During recovery, limited trust slows progress. Horses may refuse hand walking or therapy exercises unless the bonded person is present. This dependence complicates scheduling and delays healing, especially in busy clinics or boarding barns where rotating staff manage care across shifts and emergencies requiring calm cooperation from every interaction throughout recovery periods.

7. Loss of the bonded person triggers regression.

When a favored handler leaves, retires, or becomes unavailable, horses can regress rapidly. Learned behaviors fade. Anxiety resurfaces. The horse may appear confused, withdrawn, or reactive.

This transition is common during sales, relocations, or staffing changes. Without a broad trust base, the horse must rebuild security from scratch. That process takes time and increases accident risk during adjustment periods particularly in unfamiliar environments with new routines, equipment, and social expectations that overwhelm sensitive individuals quickly without structured support systems present.

8. Handlers may unknowingly reinforce dependency behaviors over time.

Extra attention, constant reassurance, and exclusive handling feel compassionate. To the horse, these signals confirm reliance. Subtle habits accumulate, deepening attachment without intention.

Preventing dependency requires awareness. Rotating handlers, neutral responses, and shared routines distribute trust. When care is consistent across people, horses relax into predictability rather than clinging to a single emotional anchor which ultimately supports safety, training continuity, and welfare across long term management situations in barns, programs, and varied ownership contexts that frequently change over years unexpectedly.

9. Balanced bonds protect horses and humans alike.

Healthy relationships involve trust without exclusivity. Horses benefit from multiple calm caregivers who communicate clearly. This mirrors natural herd stability, where safety comes from many signals, not one.

When bonds are balanced, horses adapt smoothly to change. Training holds steady. Stress stays manageable. The result is a safer environment where partnership supports independence rather than fragile dependence across daily handling, emergencies, and the many transitions horses experience during their working lives with confidence instead of fear responses from routine disruptions.