Scientists document catastrophic marine ecosystem collapse.

A comprehensive study published in Royal Society Open Science reveals the stark mathematics of climate-driven extinction. Between 2012 and 2021, approximately 7,000 humpback whales died in the North Pacific Ocean, reducing the population by 20 percent from its peak of 34,500 individuals. The culprit was “The Blob”—a marine heat wave that elevated sea surface temperatures by up to 7 degrees Fahrenheit across 2 million square miles of ocean for four consecutive years.

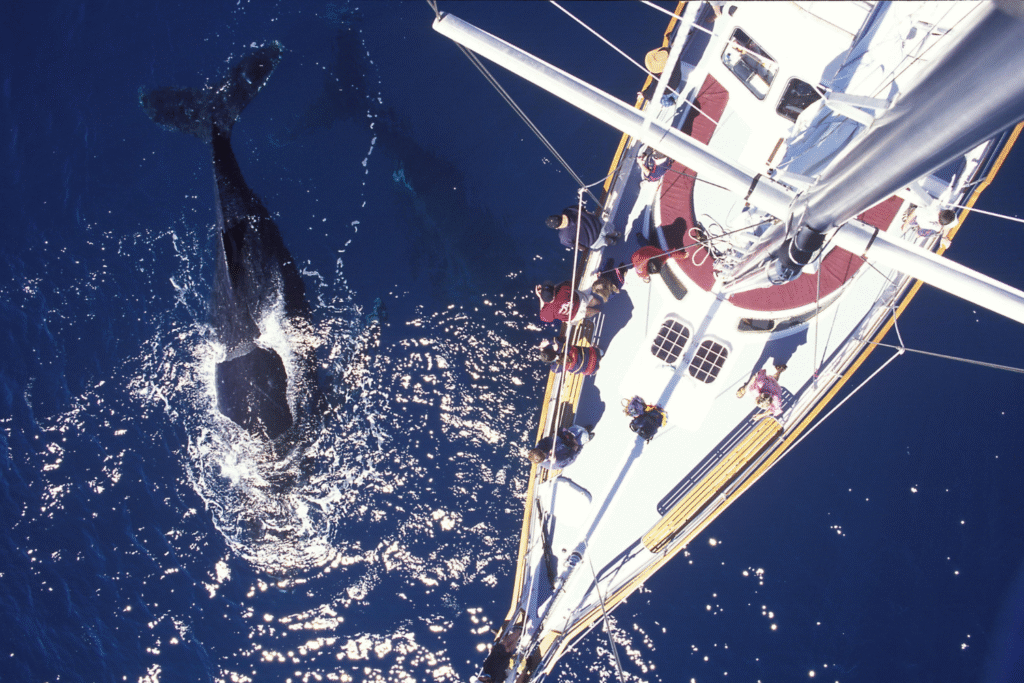

Population models constructed using artificial intelligence analysis of over 400,000 whale photographs demonstrate how rapidly climate change can unravel decades of conservation success. What required 40 years of international protection to achieve has been decimated in less than a decade by ocean warming patterns.

1. Scientists documented a 20 percent population collapse using cutting-edge AI technology.

Artificial intelligence helped researchers piece together one of the most comprehensive wildlife population studies ever conducted. Using machine learning to analyze thousands of whale photographs collected over two decades, scientists tracked individual animals through a massive citizen science database. The technology allowed them to identify unique tail patterns and create detailed population models that revealed the scope of this ecological disaster.

According to a study published in Royal Society Open Science in February 2024, the North Pacific humpback whale population plummeted from its 2012 peak of nearly 34,500 individuals to approximately 26,600 by 2021. This represents more than just numbers on a chart—it’s the collapse of one of conservation’s greatest success stories, undone by forces beyond traditional wildlife management.

2. The Blob emerged as nature’s most destructive force in modern ocean history.

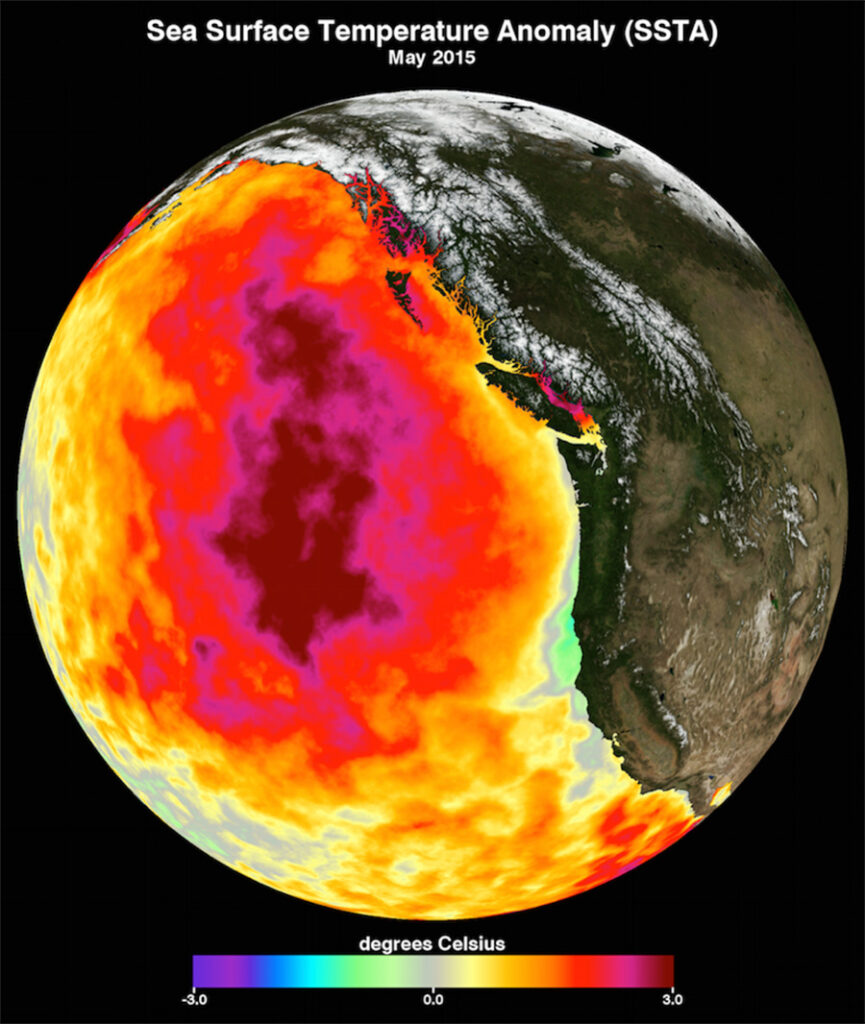

Marine biologists had never witnessed anything quite like it before 2013. A massive dome of unusually warm water began forming in the northeastern Pacific, eventually spanning from Alaska to Baja California in what scientists grimly dubbed “The Blob.” Temperatures spiked by up to 7 degrees Fahrenheit above normal, fundamentally altering ocean chemistry and food webs across millions of square miles.

This wasn’t your typical seasonal warming pattern or short-lived weather anomaly, as reported by researchers from Southern Cross University who led the groundbreaking population study. The heat persisted for four relentless years, systematically dismantling the intricate marine food chains that humpback whales had depended on for millennia. Ocean currents shifted, nutrient distributions changed, and the delicate balance that sustained these massive creatures began crumbling from the bottom up.

3. Starvation became the silent killer stalking whales across their ancient migration routes.

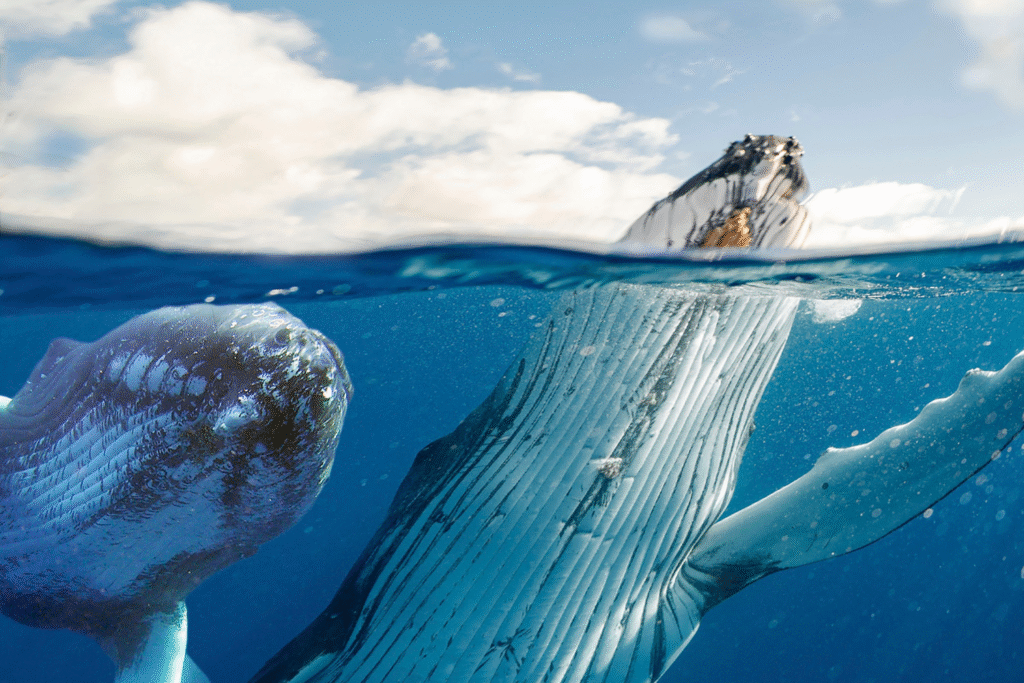

Imagine traveling 3,000 miles to your traditional feeding grounds only to find them barren. Hawaiian waters, which had welcomed migrating humpbacks for countless generations, recorded a population decline of more than one-third during the heat wave period. These weren’t random deaths scattered across the ocean—they followed predictable patterns that revealed the systematic breakdown of marine ecosystems.

As discovered by Ted Cheeseman, the study’s lead author and doctoral student at Australia’s Southern Cross University, the whales essentially outgrew their environment’s capacity to sustain them. Krill populations collapsed, baitfish disappeared, and the ocean’s productivity plummeted just as the whale population reached historic recovery levels. The timing couldn’t have been more catastrophic for a species that had spent four decades clawing back from the brink of extinction.

4. Commercial whaling’s legacy made this climate disaster even more devastating.

The bitter irony cuts deep when you understand the timeline. These whales had survived humanity’s first attempt at their extinction through industrial whaling, which reduced North Pacific populations to roughly 1,200 individuals by 1976. International protection allowed them to recover slowly, reaching about 17,000 by 2002 before surging to their 2012 peak. But this remarkable comeback story contained the seeds of their climate vulnerability.

Recovery had restored whale numbers faster than ocean productivity could sustainably support them. When marine heat waves struck, the population had reached what scientists call “carrying capacity”—the maximum number of individuals their environment could maintain. Climate change didn’t just kill whales directly; it reduced the ocean’s ability to feed them precisely when they needed it most.

5. Female whales bore the heaviest burden as reproduction rates plummeted.

Starvation doesn’t kill whale populations evenly. Pregnant and nursing females require enormous caloric intake to support their young, making them especially vulnerable when food becomes scarce. During the heat wave years, birth rates dropped significantly as malnourished mothers either failed to conceive or couldn’t successfully raise calves to weaning age.

The reproductive crash amplified the population decline beyond simple mortality numbers. Not only were more whales dying, but fewer were being born to replace them. This demographic double-hit explains why populations fell so dramatically and why recovery may prove much more challenging than previous conservation efforts. Each lost breeding female represents not just one death, but potentially dozens of future calves that will never exist.

6. Hawaii’s waters transformed from nursery to graveyard for migrating giants.

Hawaiian waters have served as the primary breeding and calving grounds for North Pacific humpbacks for thousands of years. These warm, protected waters provided perfect conditions for mothers to give birth and nurse their young before the arduous journey back to feeding areas. But the heat waves disrupted even these sacred spaces, fundamentally altering water temperatures and current patterns.

Scientists now predict that continuing ocean warming could make Hawaiian waters too hot for humpback comfort within decades. If whales abandon their traditional breeding grounds, it would represent an unprecedented disruption to migration patterns that have remained stable since the last ice age. The implications extend far beyond whale populations to include Hawaii’s tourism industry and the cultural significance these animals hold for Pacific Island communities.

7. Ocean food webs collapsed from the microscopic level upward.

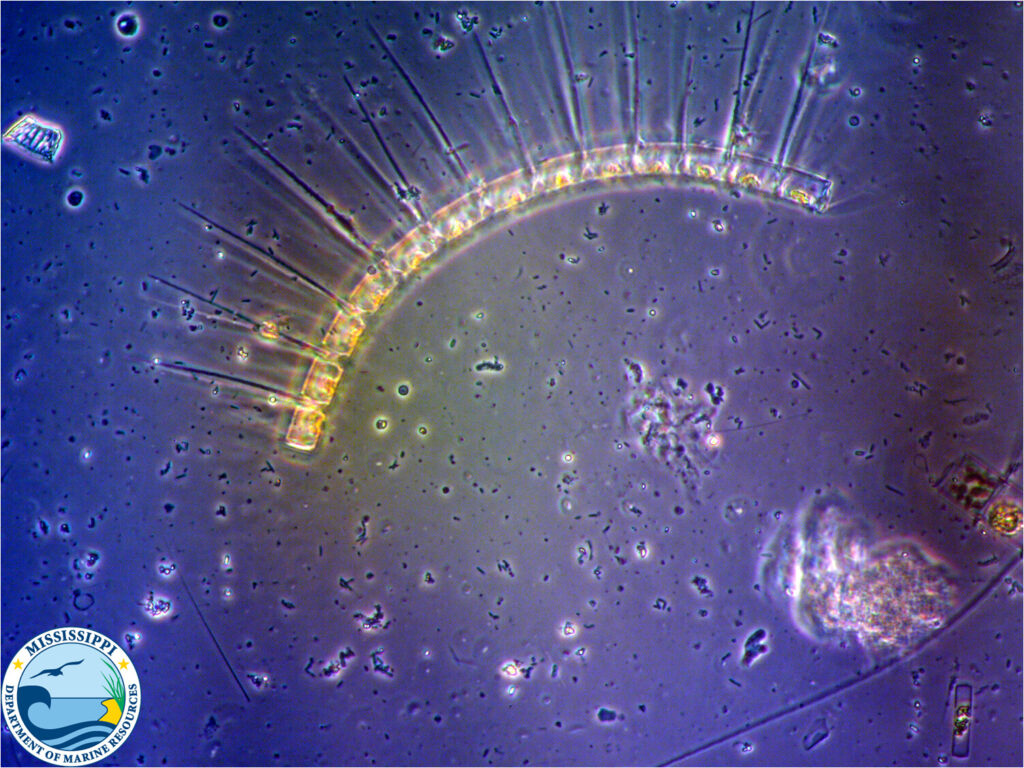

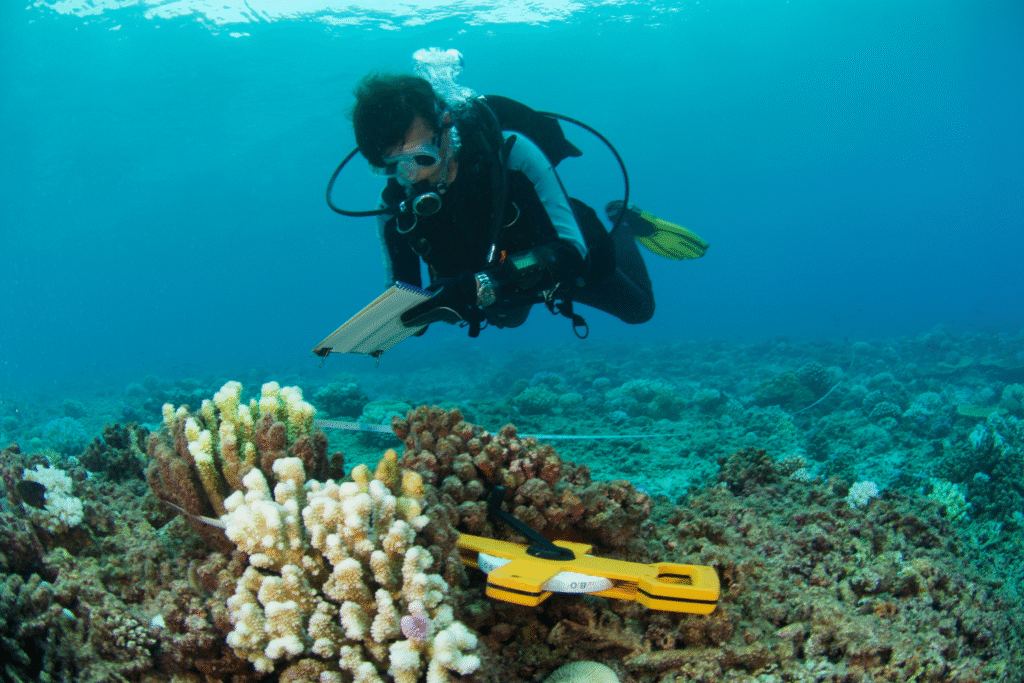

The destruction began with the smallest organisms and cascaded upward through every level of marine life. Phytoplankton, the microscopic plants that form the foundation of ocean food webs, suffered massive die-offs as temperatures exceeded their tolerance ranges. This triggered a domino effect that devastated zooplankton, krill, small fish, and eventually the whales themselves.

Understanding this collapse requires thinking in terms of energy transfer. When phytoplankton populations crash, there’s simply less energy entering the entire marine ecosystem. Each level up the food chain compounds these losses, meaning apex predators like humpback whales face exponentially reduced food availability. The mathematical reality is harsh but simple—fewer microscopic organisms mean fewer whales can survive.

8. Climate models predict this tragedy represents just the beginning.

Current climate projections suggest that what scientists classify as extreme heat events today may become normal ocean conditions within two decades. The marine heat wave that killed thousands of whales was unprecedented in recorded history, but computer models indicate such events will likely occur with increasing frequency and intensity as global temperatures continue rising.

This creates a terrifying scenario for whale populations that evolved over millions of years to adapt to relatively stable ocean conditions. If today’s extreme becomes tomorrow’s baseline, the carrying capacity of North Pacific waters may permanently decline to levels that cannot support current whale populations. The recent die-off may not represent a temporary setback but rather a preview of perpetual population pressure driven by climate change.

9. Conservation success stories crumble when climate change accelerates beyond adaptation.

The humpback whale recovery had been marine conservation’s poster child for four decades. International cooperation, strict hunting moratoriums, and dedicated protection efforts had seemingly proven that humans could reverse even the most severe wildlife population crashes. This success story inspired similar efforts for countless other endangered species worldwide.

But climate change operates on scales and timelines that dwarf traditional conservation approaches. While conservationists spent decades protecting whales from ships, fishing nets, and hunting, the ocean itself was changing in ways that made those protections irrelevant. The sobering lesson is that species conservation in the climate era requires addressing the fundamental systems that sustain life, not just the direct human threats that endanger it.

10. Recovery prospects dim as ocean conditions continue deteriorating worldwide.

Marine biologists face the grim reality that humpback whale populations may never fully recover to their 2012 peak levels. Current ocean conditions show no signs of returning to the stable temperatures and productivity patterns that supported historical whale populations. Instead, marine heat waves are becoming more frequent and intense across all major ocean basins, creating a new normal that fundamentally alters marine carrying capacity.

The cascading effects extend far beyond humpback whales to encompass entire Pacific marine ecosystems. Salmon runs have collapsed, seabird colonies have abandoned traditional nesting sites, and commercial fisheries report the worst catches in decades. Scientists warn that the North Pacific die-off represents an early indicator of ecosystem-wide collapse that could reshape ocean life permanently, making the whale deaths a canary in the coal mine for much larger environmental catastrophes ahead.