A pause may only rearrange the pressure.

When people imagine global warming slowing, they picture relief. In reality, Earth stores enormous amounts of heat in oceans, soils, and ice, energy that does not disappear when surface temperatures pause. If warming temporarily slows due to natural cycles or pollution changes, that stored heat can resurface. Scientists warn this rebound effect could accelerate warming later, reshaping weather patterns and ecosystems. A slowdown, paradoxically, may set the stage for sharper climate shifts rather than lasting stability in coming decades worldwide.

1. Oceans continue releasing heat long after warming slows.

The world’s oceans absorb the vast majority of excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases. Even if surface temperatures stabilize briefly, deeper layers continue holding and circulating stored energy. According to NASA climate monitoring data, ocean heat content has increased steadily regardless of short term changes in atmospheric warming rates.

That heat does not remain isolated. It resurfaces through currents, evaporation, and altered weather systems. Warm water fuels stronger storms and marine heatwaves years after absorption. A slowdown in air temperatures can coexist with intensifying ocean driven impacts, creating the illusion of relief while powerful forces remain active beneath the surface.

2. Ice systems release energy after critical thresholds pass.

Glaciers and ice sheets act as temporary heat sinks. As warming slows, melting does not instantly stop because the ice already absorbed energy. As stated by the National Snow and Ice Data Center, ice loss often continues even during periods of slower atmospheric warming.

Once structural thresholds are crossed, collapse accelerates. Melting releases stored heat into surrounding water and air, amplifying regional warming. This delayed response means cooling trends can coincide with rapid ice loss. The system responds to accumulated energy, not current conditions, producing abrupt changes after apparent stabilization.

3. Permafrost responds on a delayed thermal timeline.

Frozen soils across the Arctic have absorbed heat for decades. Even if air temperatures level off, underground warming continues. As reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, permafrost thaw lags significantly behind surface temperature trends.

As thaw progresses, heat escapes upward while methane and carbon dioxide are released. These gases trap additional heat, reinforcing warming even during surface slowdowns. The land retains memory of past heat exposure. Once thaw begins, it follows internal dynamics rather than short term atmospheric changes, making reversals difficult.

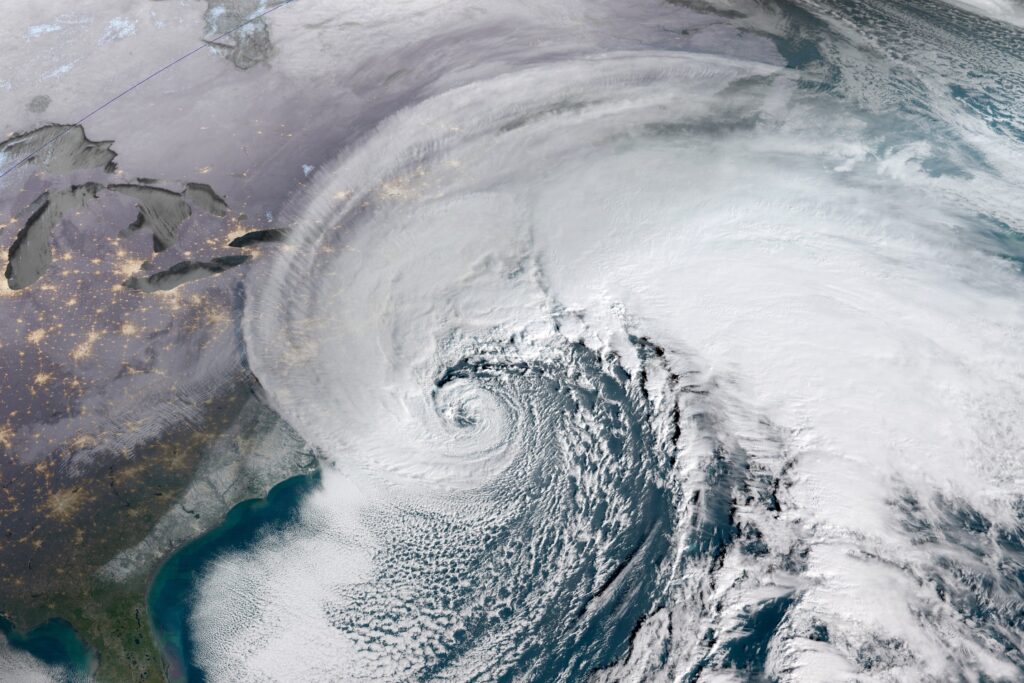

4. Atmospheric circulation redistributes stored energy unevenly.

Slower global averages do not mean calmer weather. Heat already embedded in the atmosphere shifts location through altered jet streams and pressure systems. Energy moves sideways rather than upward.

This redistribution creates extremes. Some regions experience prolonged heatwaves while others cool temporarily. Storm paths shift. Weather volatility increases. A slowdown in global averages can mask growing instability as stored energy concentrates unevenly, producing sharper local impacts that feel disconnected from overall trends.

5. Clouds amplify release rather than neutralizing heat.

Clouds respond dynamically to moisture and temperature changes. Some reflect sunlight, cooling surfaces. Others trap heat, especially overnight. When warming slows, cloud behavior can amplify the release of stored energy rather than dampen it.

Rising humidity favors heat trapping clouds in many regions. Nights warm faster than days. Heat remains locked in urban and coastal areas. These subtle feedbacks turn slowdowns into misleading signals while energy continues cycling through the climate system in less visible ways.

6. Ocean circulation reacts decades after heat absorption.

Large scale ocean currents respond slowly to temperature shifts. Systems like the Atlantic overturning circulation adjust over decades, not years. Even if warming slows, these currents continue responding to earlier heat input.

As circulation weakens or reroutes, heat resurfaces in unexpected regions. Coastal climates change. Fisheries shift. Storm behavior evolves. Present conditions reflect past emissions, not current ones. This delay ensures continued change long after surface warming appears to pause.

7. Natural cooling events only mask stored imbalance.

Volcanic eruptions and solar cycles can temporarily cool the planet. Aerosols reflect sunlight, lowering surface temperatures briefly. These effects do not remove stored heat.

Once aerosols dissipate or solar output shifts, hidden energy reemerges. Temperature rebounds can feel sudden and alarming. These fluctuations disguise deeper imbalance, creating false confidence during cooling phases while underlying energy remains trapped within Earth systems.

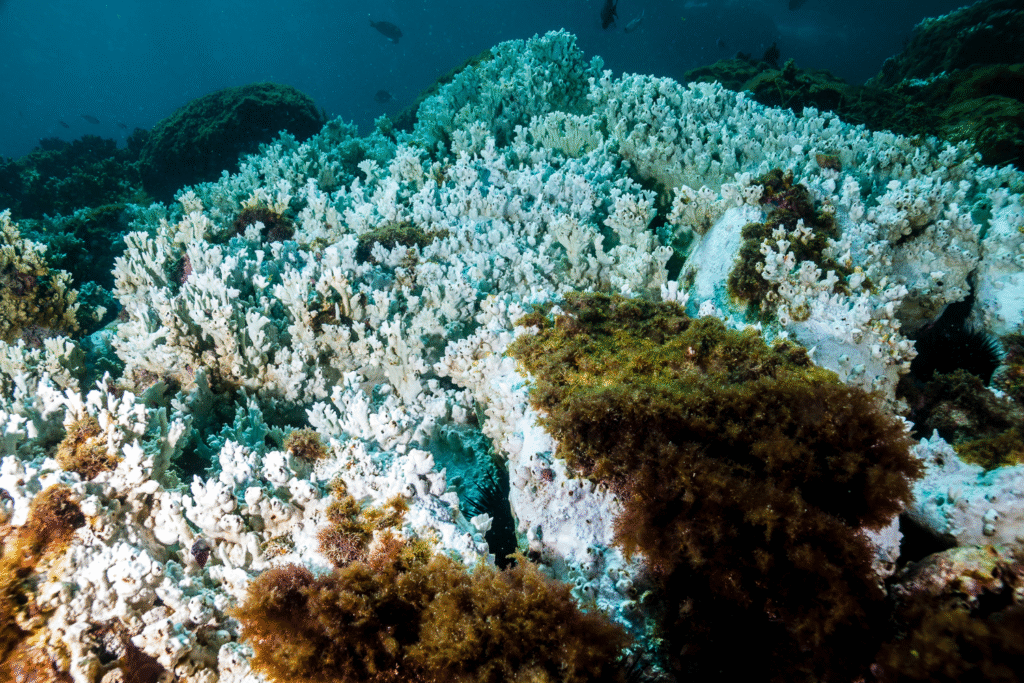

8. Ecosystems respond to cumulative heat exposure.

Biological systems track long term stress, not short term averages. Coral reefs, forests, and wildlife accumulate damage over time. A pause in warming does not reset thresholds.

Heat stored in oceans and soils continues stressing ecosystems. Coral bleaching events often follow delayed ocean warming. Forests weakened by past heat succumb years later. Ecological collapse frequently appears after stabilization, revealing the lag between exposure and consequence.

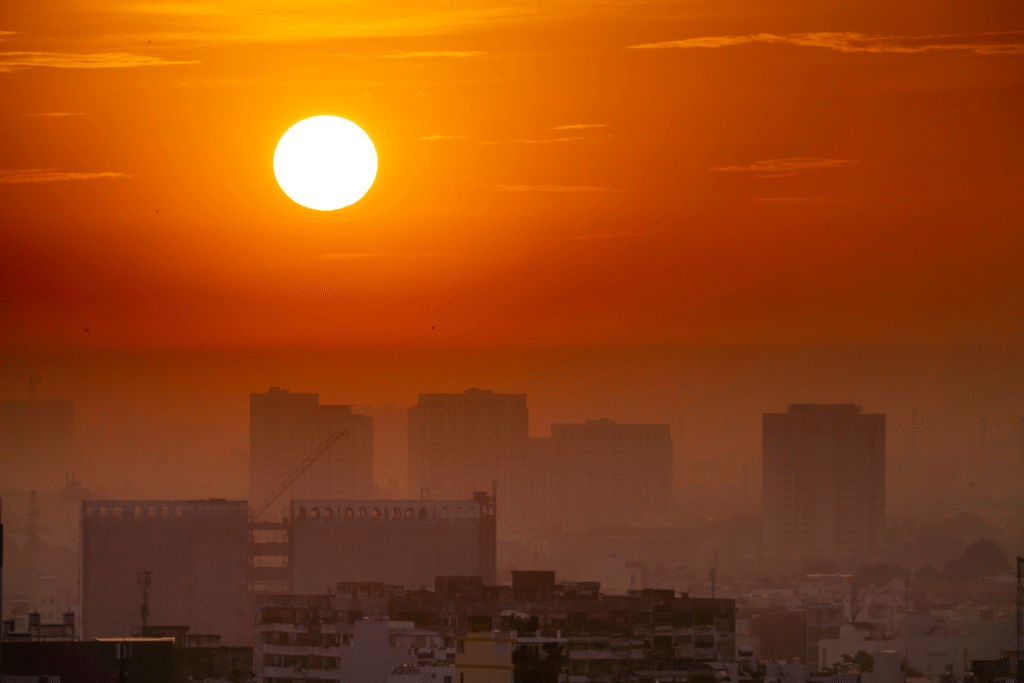

9. Cities slowly release decades of absorbed heat.

Urban environments absorb and retain heat in concrete, asphalt, and infrastructure. Even when regional warming slows, cities continue reemitting stored energy.

This prolongs heatwaves and raises nighttime temperatures, straining power grids and health systems. Cooling demand remains high. Urban heat islands act as reservoirs, feeding warmth back into the atmosphere gradually. The built environment responds slowly, extending heat impacts beyond atmospheric trends.

10. Climate systems operate on momentum, not intention.

Earth does not respond to desire or policy announcements. Heat already absorbed determines future behavior. A slowdown changes how energy moves, not whether it exists.

Stored heat surfaces through oceans, land, air, and ecosystems on delayed schedules. Stability requires sustained reductions over long periods. Anything shorter reshuffles pressure rather than releasing it. What follows a slowdown is often not calm, but a different phase of consequence unfolding.