Ancient canals resurface as modern water systems fail.

As drought tightens its grip across the American Southwest, scientists are looking backward instead of forward. Beneath modern cities, farms, and highways lie irrigation systems engineered centuries ago by Indigenous communities who survived long dry periods without dams, pumps, or concrete. These networks were not isolated experiments. They were region wide systems tuned to desert climates that mirror today’s extremes. As reservoirs drop and aquifers decline, researchers are realizing these forgotten canals may offer practical guidance for water survival now.

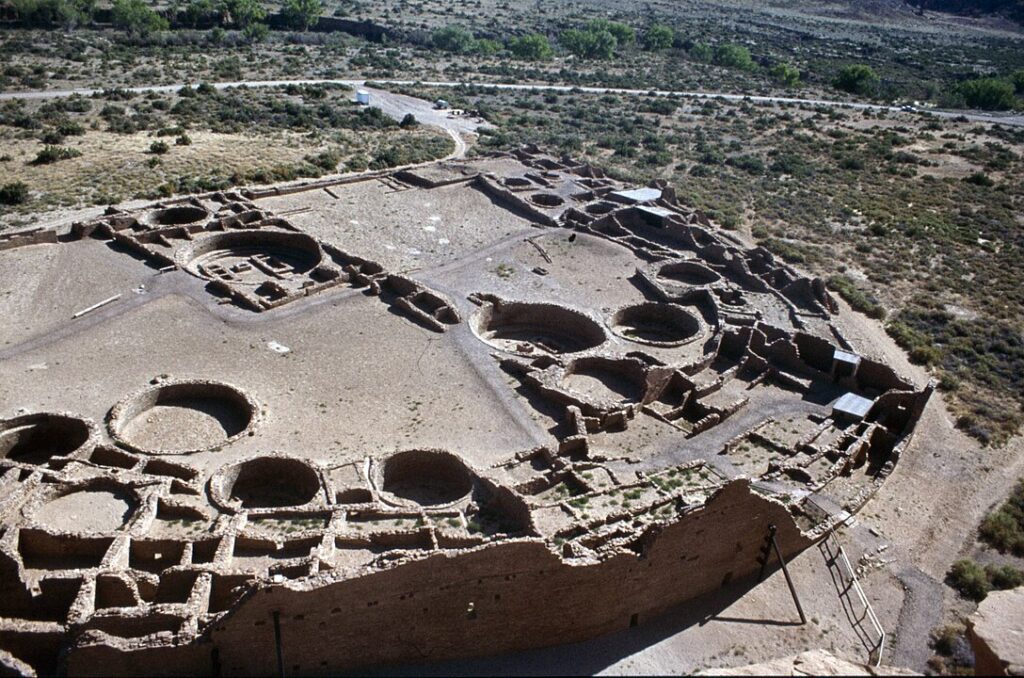

1. The Hohokam canal system reshaped central Arizona.

Between roughly 300 and 1450 CE, the Hohokam people built one of the largest irrigation networks in North America. Their canals followed the Salt and Gila Rivers across what is now the Phoenix metropolitan area. Some canals stretched more than fifteen miles and were wide enough to walk through comfortably.

These waterways irrigated tens of thousands of acres and supported large population centers in extreme heat. Modern satellite mapping shows Phoenix streets still align with ancient canal routes. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the Hohokam canal system exceeded five hundred miles in total length and functioned through centuries of drought using gravity alone.

2. Ancestral Pueblo systems captured scarce mountain runoff.

In northern New Mexico and southern Colorado, Ancestral Pueblo communities developed irrigation methods suited for rocky terrain and limited rainfall. Rather than long canals, they built stone check dams, terraced fields, and diversion channels to slow snowmelt and monsoon runoff near Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde.

Water was spread gently across fields instead of forced through channels. This reduced erosion and allowed soil to absorb moisture slowly. Archaeologists studying these sites found repeated rebuilding rather than abandonment. As reported by National Geographic, these systems allowed agriculture to persist during long dry cycles that closely resemble current Southwest drought patterns.

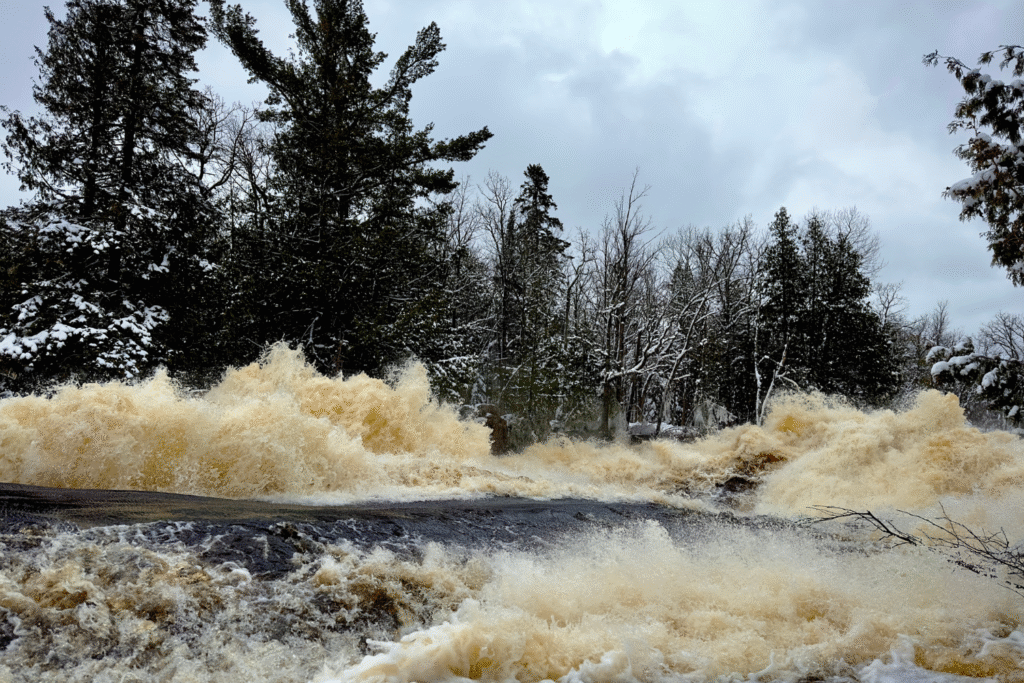

3. The Ak Chin system relied on seasonal desert floods.

In southern Arizona, the Tohono O’odham Nation developed the Ak Chin irrigation method, designed specifically for desert washes. Instead of permanent canals, low earthen berms guided seasonal floodwater from mountain storms onto agricultural fields below.

This approach worked with unpredictable rainfall rather than against it. Fields received water only when floods arrived, reducing dependence on constant flow. The system also recharged soil moisture naturally. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, Ak Chin irrigation proved remarkably resilient in arid environments and is now being studied for modern flood control and groundwater recharge applications.

4. Zuni runoff farming shaped entire landscapes.

In western New Mexico, Zuni farmers created runoff irrigation systems that redirected rainwater across broad landscapes. Stone alignments and shallow channels guided water into fields planted with corn, beans, and squash. These systems were subtle and easily missed from ground level.

Rather than forcing water downhill, the Zuni slowed it, spreading moisture evenly and reducing erosion. This method worked even during years with minimal rainfall. The design shows how drought survival depended on water patience rather than volume, a principle modern engineers are now reconsidering.

5. Canal governance prevented conflict during scarcity.

These irrigation networks were managed collectively. Canal branches often aligned with household clusters, suggesting shared responsibility for maintenance and distribution. Water access followed seasonal agreements rather than rigid ownership.

When shortages occurred, usage adjusted across the community. Archaeologists found few signs of conflict tied to water stress in these regions. This contrasts sharply with modern legal disputes over water rights. The success of these systems depended as much on social organization as engineering, a lesson increasingly relevant as scarcity intensifies today.

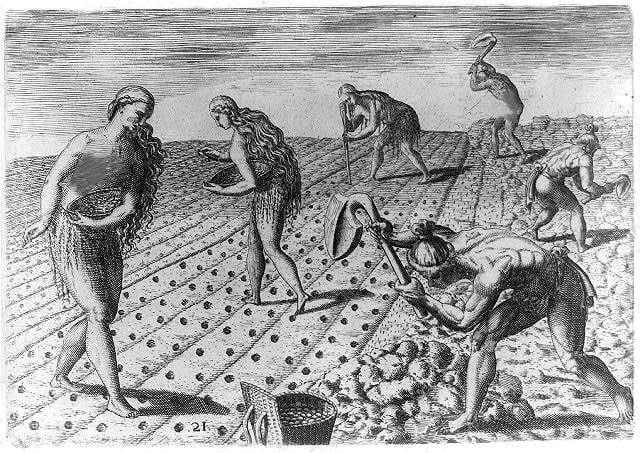

6. Crop choices reduced failure during extreme years.

Indigenous farmers selected crops adapted to irregular watering. Corn, beans, squash, and native grasses survived both dry spells and sudden flooding. Fields were planted where overflow naturally reached them, not where constant irrigation was required.

This strategy reduced catastrophic crop loss. Diversity acted as insurance against climate swings. Modern monoculture farming depends on stable water delivery, making it vulnerable during drought. These ancient systems show how agricultural resilience can emerge from flexibility rather than control.

7. Canal placement protected soil and groundwater.

Rather than draining landscapes, Indigenous canals enhanced wetlands and recharge zones. Water moved slowly, allowing infiltration into aquifers. Sediment carried by floods replenished soil nutrients instead of washing fields away.

Today, aquifers across the Southwest are declining rapidly. Ancient designs suggest that slowing water movement may be as important as storing it. The focus was not extraction but circulation, a concept now gaining attention among hydrologists seeking sustainable drought solutions.

8. Modern cities sit directly atop ancient canals.

In Phoenix, parts of the modern canal system mirror Hohokam routes almost exactly. Early settlers reused these paths because they followed optimal gradients already tested over centuries.

This overlap highlights how ancient engineering still shapes modern infrastructure. It also raises questions about whether current systems could be adapted rather than replaced. Researchers mapping buried canals believe integrating old pathways could reduce energy use and improve resilience without massive reconstruction.

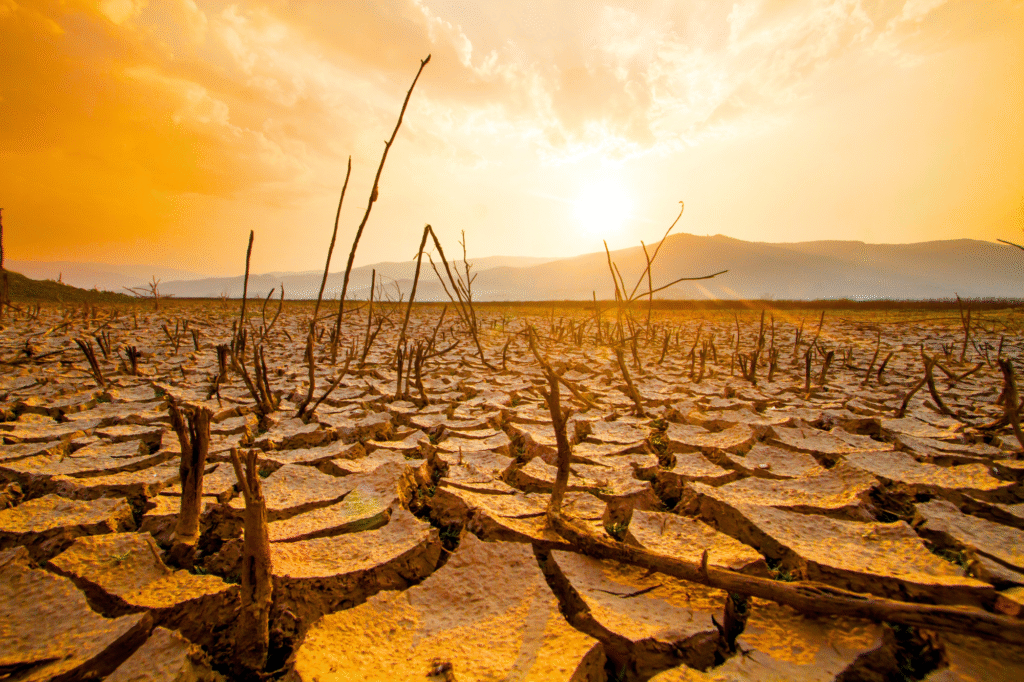

9. Climate conditions now resemble ancient megadroughts.

Tree ring studies show the Southwest experienced decades long megadroughts during the periods these systems operated. Despite extreme conditions, communities persisted through adaptive water management rather than technological escalation.

Modern systems assume predictable snowpack and runoff, assumptions now failing. Ancient irrigation was designed for uncertainty. Its survival through past extremes suggests that flexibility, not precision, may be key to enduring future drought cycles.

10. Reviving these systems requires Indigenous leadership.

These irrigation networks are not relics. Descendant communities still hold cultural knowledge tied to water management. Successful modern projects involve tribal governments as equal partners, not historical footnotes.

Revival is not about copying blueprints. It is about restoring relationships between land, water, and people. As drought worsens, the future of water resilience may depend on listening to solutions already tested beneath our feet.