A hidden biosphere lives beneath our feet.

Far below forests, cities, and ocean floors, something has been alive longer than mammals have walked the Earth. It does not depend on sunlight. It does not migrate with seasons. It survives in rock pores, fractures, and deep sediments where temperatures climb and oxygen disappears. For decades, scientists suspected life might exist there. Now drilling expeditions, genomic sequencing, and chemical analysis are revealing something far more expansive, and far older, than anyone expected.

1. Scientists now confirm a vast deep biosphere.

For years, microbes found deep underground were dismissed as contamination or recent migrants from the surface. That explanation no longer holds. Careful drilling projects in ocean crust and continental rock have recovered organisms thriving kilometers below ground.

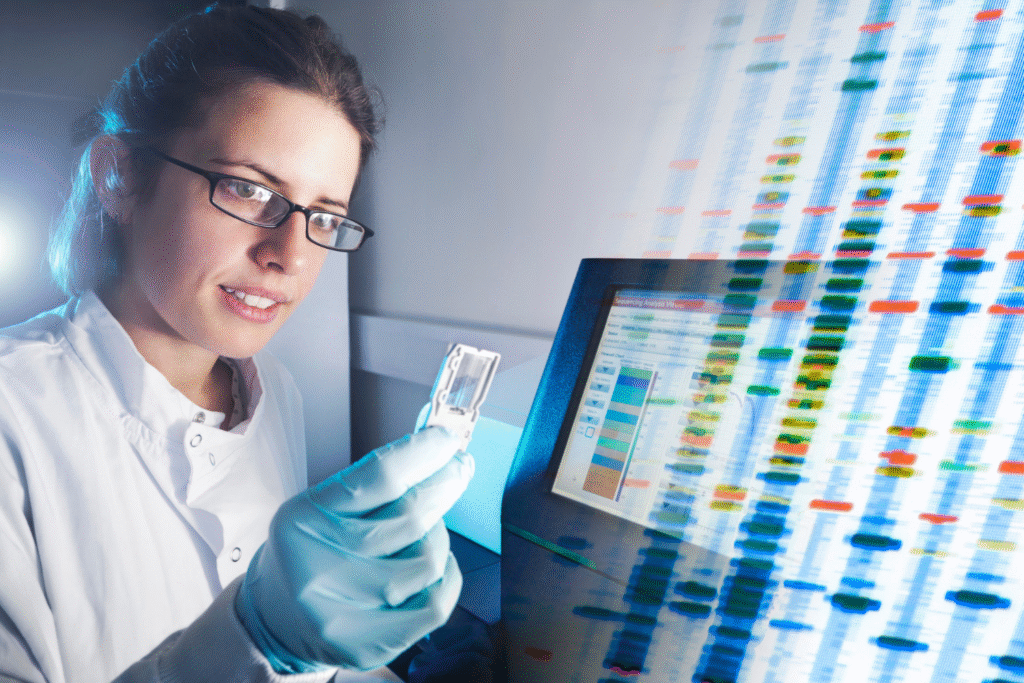

According to Princeton University Press, Karen G. Lloyd’s 2025 book “Intraterrestrials: Discovering the Strangest Life on Earth”, compiles decades of evidence showing that these subsurface microbes form a massive, long term biosphere. Lloyd, a microbial biogeochemist at the University of Southern California Dornsife, documents how genetic sequencing confirms these organisms are adapted specifically to deep, energy limited environments rather than accidental intruders.

2. These organisms survive without sunlight or oxygen.

Surface life depends on photosynthesis and oxygen driven metabolism. Deep life operates differently, raising questions about how it persists at all in darkness and pressure.

As stated by Karen G. Lloyd in her research at USC Dornsife, many of these microbes rely on chemical energy derived from rocks, hydrogen, methane, and metal reactions. They metabolize slowly, sometimes dividing only once in centuries. This alternative biochemistry suggests that life can endure independently of surface ecosystems, reshaping assumptions about what environments are truly habitable.

3. Evidence comes from ocean crust and mines.

Sampling has occurred in deep sea drilling sites, gold mines in South Africa, and boreholes beneath continental crust. Each site extends the known limits of life farther underground.

As reported by Princeton University Press, microbes have been identified several kilometers below the seafloor and deep within terrestrial rock. Genetic analysis reveals entire communities structured around chemical gradients rather than sunlight. These discoveries confirm that subsurface life is not rare or isolated, but geographically widespread across the planet.

4. Their biomass may rival surface life.

Estimates of total subsurface microbial biomass have surprised researchers. Calculations suggest the deep biosphere could contain a significant fraction of Earth’s total microbial mass.

Because these organisms grow slowly and accumulate over immense time spans, their combined presence becomes substantial. Even though individual cells are sparse, their persistence across global crustal environments adds up. The scale forces scientists to reconsider where most of Earth’s life actually resides.

5. Many lineages diverged millions of years ago.

Genomic sequencing shows that some deep microbes split from surface relatives millions of years in the past. Their DNA reflects long isolation rather than recent burial.

Mutations accumulate slowly in energy limited conditions, preserving ancient evolutionary signatures. These lineages appear to have adapted to subsurface existence early, maintaining stability across geological epochs. The implication is not temporary refuge, but permanent residence beneath Earth’s surface.

6. Metabolism proceeds at nearly geological speeds.

Unlike bacteria that divide rapidly in nutrient rich environments, deep subsurface microbes operate at extreme metabolic limits.

Some cells may repair damage and maintain membranes without active division for decades or centuries. Energy budgets are so constrained that survival replaces growth as the dominant strategy. This slow pace challenges conventional definitions of what active life looks like.

7. The deep biosphere influences global chemistry.

Subsurface microbes interact with minerals, influencing carbon, sulfur, and methane cycles on a planetary scale.

Their metabolic byproducts can alter groundwater composition and affect long term geochemical balances. Though hidden from view, these organisms participate in processes that shape atmospheric chemistry and ocean composition indirectly over deep time.

8. Discovery required extreme contamination controls.

Confirming deep life required eliminating surface contamination. Drilling equipment was sterilized, tracer chemicals were used, and independent labs verified genetic signatures.

Without strict controls, microbes from drilling fluids could easily be mistaken for native organisms. The rigorous protocols used in ocean drilling programs and underground mines strengthened confidence that the life detected truly originated from deep environments.

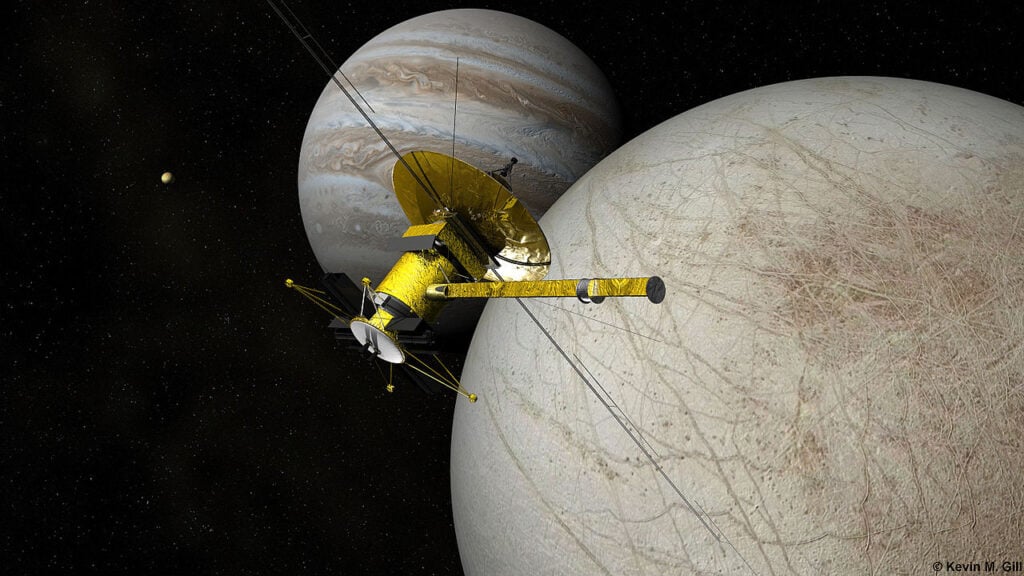

9. The concept reshapes the search for alien life.

If life thrives kilometers beneath Earth without sunlight, similar environments on Mars or icy moons become more plausible habitats.

Subsurface oceans on Europa or rock fractures on Mars may offer chemical energy sources analogous to those sustaining intraterrestrials here. The discovery does not confirm extraterrestrial life, but it expands the range of environments considered viable beyond surface conditions.