These invasions reveal cracks in aquatic defenses.

Florida’s waterways have always been busy, but something has shifted. Over the past decade, nonnative catfish have moved from odd sightings to routine catches in canals, rivers, and retention ponds. Anglers in Miami Dade noticed it first, then biologists in Tampa Bay, and now reports stretch deep into central Florida. These fish thrive in warm, altered waters shaped by development and flooding. Once established, they spread quietly, changing food webs before most people realize anything is wrong.

1. Armored catfish are expanding faster than expected.

In canals near Fort Lauderdale, armored catfish now appear year round rather than seasonally. Their bony plates and locking spines make them difficult for predators to handle. That protection allows survival rates far higher than most native bottom feeders. They graze constantly, scraping algae and plant material from rocks, concrete, and vegetation, which destabilizes banks and increases sediment in the water, according to the US Geological Survey.

Their spread is rarely dramatic. Small movements through connected canals accumulate over time. Each rainy season pushes populations into new neighborhoods, often unnoticed until numbers surge.

2. Burrowing behavior is damaging canal infrastructure.

Maintenance crews along Broward County canals began noticing sudden collapses in previously stable banks. Armored catfish excavate nesting tunnels into soft soil, weakening canal edges from within. When water levels rise quickly, those hollowed areas fail, increasing erosion and flood risk. Repairs have become more frequent and expensive as colonies expand, as stated by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

These fish reuse the same burrows year after year. Even after repairs, new collapses often appear nearby. The damage spreads invisibly until structural failure becomes obvious.

3. Aquarium releases started many infestations.

Many invasive catfish species sold in pet stores grow far larger than expected. When tanks become unmanageable, owners sometimes release fish into nearby ponds or canals. In South Florida, warm water removes the cold barrier that stops survival elsewhere. Genetic studies have traced several populations to aquarium lineages, as discovered by researchers at the University of Florida IFAS.

These releases often happen near dense urban areas. Once breeding begins, populations expand outward through drainage systems. A single release can create a permanent ecological problem.

4. Flood control canals act like open highways.

Florida’s canal system was designed to move water quickly away from developed areas. During heavy rains, those same canals move fish. Catfish are swept through spillways and gates into rivers and lakes that were once isolated. What appears contained on maps functions like a connected network during storms.

After major rainfall events, new populations appear miles from known clusters. Natural barriers no longer exist. The infrastructure built for flood protection unintentionally accelerates biological invasions.

5. Native fish lose food and shelter.

Armored catfish feed relentlessly along the bottom, stripping algae and uprooting aquatic plants. In places like the Kissimmee River basin, biologists have documented declines in sunfish and minnows after catfish establishment. Vegetation loss removes shelter for young fish and disrupts spawning areas.

Native species cannot compete with a grazer that feeds constantly. Over time, waterways shift toward fewer tolerant species. The ecosystem becomes simpler, murkier, and less resilient.

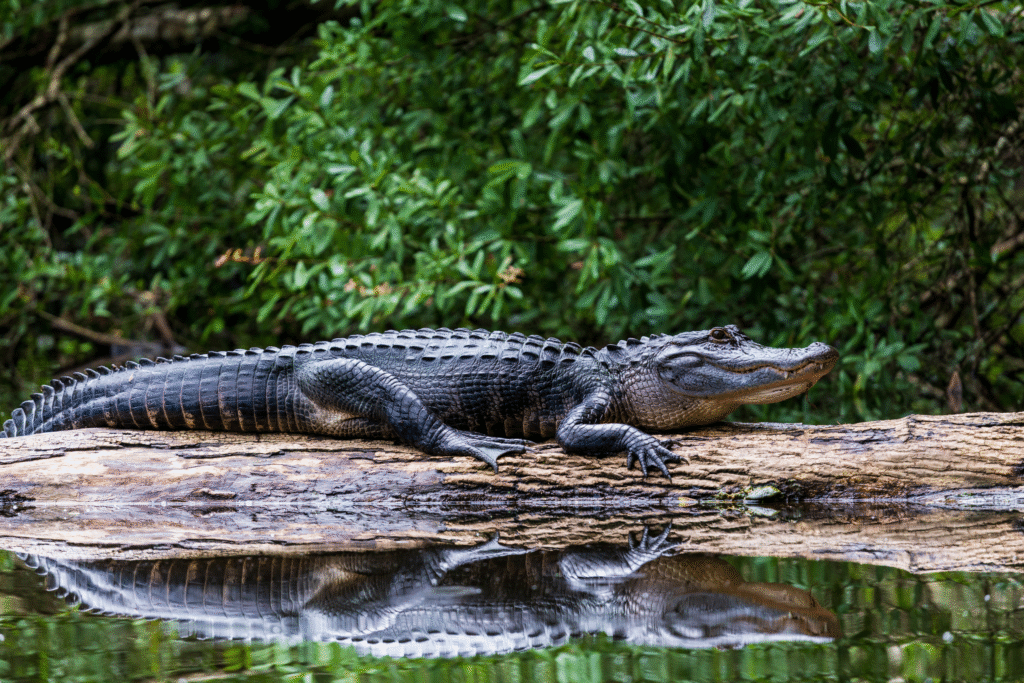

6. Few predators know how to eat them.

Alligators can crush armored catfish, but most predators avoid them. Their rigid spines can lodge in mouths and throats, sometimes killing birds or fish that attempt to swallow them. This defense removes a key population control.

In waterways near Naples, catfish biomass now exceeds that of native bottom feeders combined. With eggs guarded in burrows and few predators, survival rates remain high. Population growth continues with little resistance.

7. Human altered waters favor catfish survival.

Warm runoff, nutrient pollution, and low oxygen conditions stress many native fish. Armored catfish tolerate these conditions easily. Retention ponds, slow canals, and drainage ditches around new developments become ideal habitat.

Each artificial water body functions as a stepping stone. These fish do not need pristine rivers. They thrive in modified systems created for human convenience. As long as waterways remain altered, catfish retain a competitive edge.

8. Removal efforts struggle to keep pace.

Netting events and targeted fishing remove thousands of catfish annually, yet populations rebound quickly. Eggs remain protected in burrows, untouched by removal efforts. Limited funding restricts how often crews can return to cleared sites.

Without constant pressure, numbers recover within months. Management becomes repetitive rather than preventative. The effort slows expansion but rarely reverses it. Long term success depends on stopping new introductions entirely.

9. Climate trends are extending their range.

Florida winters are becoming milder. Cold snaps that once limited tropical catfish survival now occur less often. This allows gradual movement northward into regions previously unsuitable.

Models suggest suitable habitat expanding toward northern Florida over coming decades. What began as a South Florida issue is no longer contained there. Rising temperatures quietly remove natural limits, enabling continued spread into new watersheds.

10. Early reporting is the strongest remaining defense.

Biologists rely heavily on anglers and residents to report unusual catches. Early detection allows rapid response before populations become entrenched. Once catfish dominate a waterway, options narrow significantly.

Public education now emphasizes never releasing pets and reporting sightings promptly. Florida’s waterways are tightly connected. Delays allow invasive species to establish footholds that become nearly impossible to remove later.