What lies beneath the Boyne is unsettling.

Archaeologists working farmland in County Meath did not expect to uncover a settlement on this scale. What began as routine geophysical surveys near the River Boyne revealed dense, overlapping signals stretching far beyond isolated habitation. The location sits just two to three kilometers from Newgrange, Knowth, and Dowth, yet outside their protected cores. Early findings suggest permanent domestic life, not ritual spillover. The stakes are high. If confirmed, this site forces a reckoning with how many people lived here, how they organized space, and how complex everyday life really was in prehistoric Ireland.

1. The settlement’s size exceeds anything previously confirmed.

Magnetometry surveys revealed subsurface features spanning more than fifty hectares, dwarfing any known prehistoric settlement in Ireland. Instead of discrete clusters, researchers identified continuous patterns of structures, boundaries, and enclosures suggesting a single, expansive inhabited landscape. The sheer scale immediately raised doubts about long held assumptions of sparse Neolithic populations.

According to the National Monuments Service of Ireland, overlapping construction phases appear across the surveyed area. These layers indicate sustained growth over generations rather than short term occupation. A footprint this large implies thousands of residents may have lived here, pushing Irish prehistory into unfamiliar demographic territory.

2. Its placement suggests deliberate control of landscape.

The site occupies fertile lowland in County Meath with direct access to the River Boyne and surrounding arable soils. Such positioning would have allowed residents to manage water, crops, and movement through eastern Ireland with precision. This was not marginal land chosen by chance.

As reported by University College Dublin researchers, the settlement’s proximity to productive farmland and natural routeways points to planned placement. Control over food production and transport corridors suggests strategic thinking and long term investment, reinforcing interpretations of the site as a central population hub rather than a peripheral village.

3. Structural patterns imply coordinated social planning.

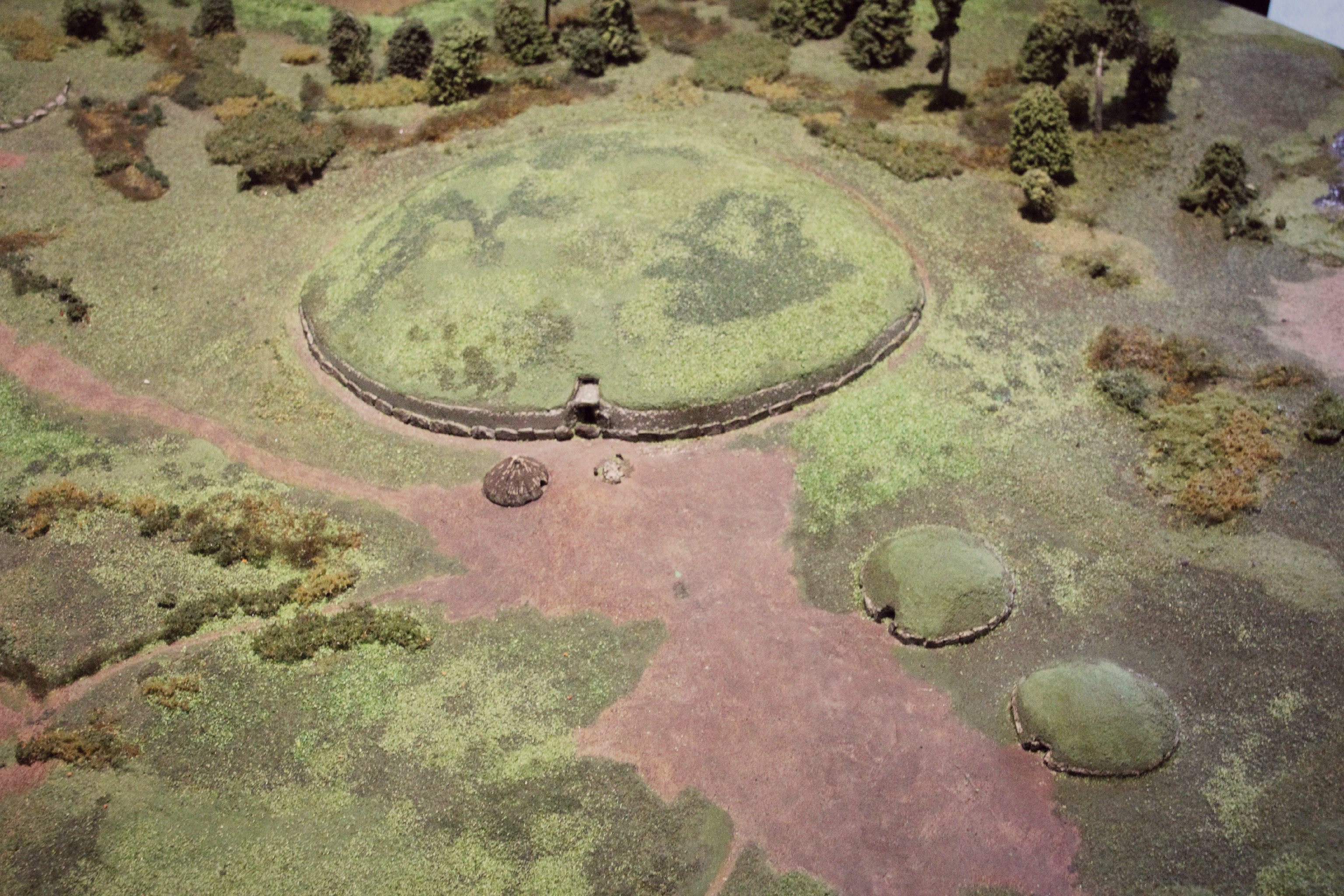

Geophysical imaging revealed dozens of probable roundhouse footprints aligned in repeated orientations across wide areas. Large curvilinear enclosure ditches, some extending hundreds of meters, frame domestic zones with striking regularity. These patterns suggest shared rules rather than individual improvisation.

As discovered by archaeologists with the Discovery Programme, internal divisions, trackways, and field boundaries reflect managed space. Such coordination implies authority capable of organizing labor, allocating land, and enforcing layouts. This challenges portrayals of loosely organized prehistoric households operating without centralized planning.

4. Evidence points to centuries of continuous occupation.

Stratigraphy and early radiocarbon sampling indicate repeated use of the site from the late Neolithic into the early Bronze Age, roughly 3000 to 2000 BCE. Construction phases overlap rather than replace one another, suggesting gradual expansion instead of abandonment.

Sustaining a settlement for centuries requires stable food systems and social cohesion. The evidence implies knowledge transfer across generations and an ability to adapt to environmental pressures without relocation. That continuity marks this community as unusually resilient for its time.

5. Agricultural systems appear unusually extensive.

Field systems, storage pits, and boundary features stretch across much of the surveyed area. These were not isolated plots but coordinated agricultural zones designed to support a dense population year round.

Storage pits consistent with grain preservation suggest surplus management and seasonal planning. Such systems would buffer against crop failure and allow population stability. The scale of agriculture reinforces interpretations of the settlement as an economic anchor rather than a fragile subsistence community.

6. Domestic artifacts suggest complex daily routines.

Excavation recovered tools linked to food processing, craft production, and household maintenance. These materials point clearly to everyday domestic life rather than ceremonial or elite activity alone.

The diversity of artifacts implies specialization within the settlement. Coordinated routines, shared infrastructure, and defined roles would have structured daily life. This complexity exceeds simple subsistence models and suggests a socially layered community with varied responsibilities.

7. Population estimates for prehistoric Ireland face revision.

Irish prehistory has long assumed small, dispersed populations. A settlement of this size directly challenges those models. Dense habitation over fifty hectares implies far more people living in proximity than previously accepted.

If similar sites remain undiscovered, national population estimates may need significant upward revision. That shift would affect interpretations of land use intensity, migration, and social interaction across prehistoric Ireland.

8. The site likely influenced surrounding regions.

A settlement of this magnitude would have shaped nearby communities through trade, marriage networks, and shared practices. Its influence likely extended well beyond County Meath.

Material similarities across eastern Ireland may now be reinterpreted as connections to this center. What once appeared as scattered cultural overlap may reflect interaction with a dominant regional hub.

9. Chronologies for social complexity may shift.

Ongoing dating may push back timelines for large scale settlement and governance in Ireland. Evidence of planning and surplus suggests complexity emerged earlier than assumed.

Rather than lagging behind continental Europe, Ireland may have hosted organized, populous communities at comparable stages. This challenges established narratives of delayed development.

10. The discovery reframes Ireland’s prehistoric narrative.

If confirmed, this settlement will force archaeologists to revisit sites previously dismissed as minor. Large populations may have been hiding in plain sight beneath farmland.

What lies beneath the Boyne suggests prehistoric Ireland was more populous, structured, and interconnected than long believed. The discovery demands a revised framework for understanding the island’s ancient past.