A hidden boundary beneath ancient Jerusalem.

For decades, scholars argued over a stubborn question about early Jerusalem. Was it a modest highland town, or a fortified political center capable of organized construction? The ground beneath the City of David held an answer, though no one recognized its scale at first. Excavations along the southeastern ridge slowly revealed something carved directly into bedrock, something too deliberate to dismiss. Only after mapping its full dimensions did archaeologists realize they were looking at infrastructure that matched descriptions long debated in biblical scholarship.

1. The City of David moat reshapes the map.

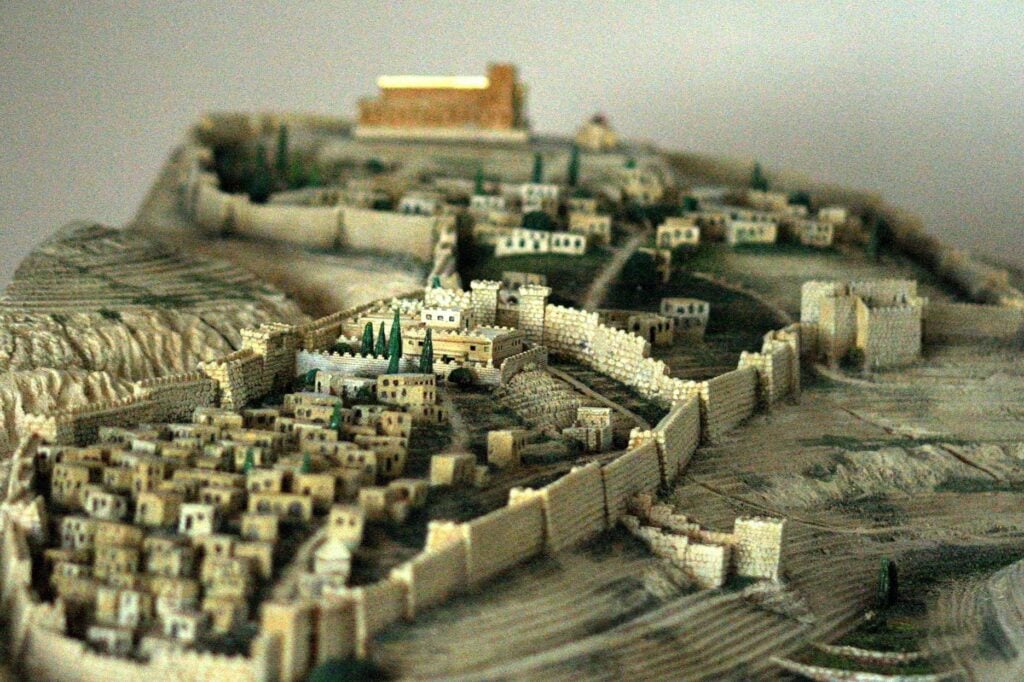

Beneath the southeastern ridge of Jerusalem, excavators uncovered a monumental rock hewn moat separating the City of David from the Ophel and Temple Mount zone. The feature is carved directly into limestone bedrock rather than built with masonry. Its dimensions are formidable, reaching roughly nine meters deep and more than thirty meters wide in certain exposed sections.

The moat physically isolates the narrow ridge from the higher northern hill. This configuration creates a dramatic drop that would have prevented direct approach from elevated terrain. Its placement suggests it functioned as a defensive barrier during Jerusalem’s early urban phase rather than a random quarry scar.

2. Iron Age pottery anchors it around 1000 BCE.

Ceramic fragments recovered from fill deposits within the cut feature date to Iron Age II, approximately the tenth century BCE. Stratigraphy confirms that later materials accumulated only after the original excavation was complete. This timeline places construction during the period traditionally associated with the early monarchy in Jerusalem.

Radiocarbon analysis of associated organic remains aligns with this date range. Archaeologists note that this era corresponds with the First Temple period. The chronological overlap intensifies scholarly debate regarding the scale of Jerusalem’s development during that time.

3. Biblical references describe fortified divisions.

Texts in Second Samuel and First Kings refer to the City of David as a fortified stronghold distinct from adjacent areas. Scholars long questioned whether these passages described symbolic or physical separations. The newly documented rock cut boundary provides tangible context for such descriptions.

While archaeology cannot verify narrative details, the existence of a large defensive separation between the ridge and the northern hill strengthens interpretations of an intentionally fortified capital. The physical landscape now mirrors elements of the textual tradition.

4. Tool marks confirm deliberate engineering.

Close examination of exposed limestone walls reveals parallel chisel impressions and consistent angles across the carved surfaces. These marks are incompatible with natural erosion or tectonic fracturing. The rock was methodically cut and removed.

Calculations suggest thousands of cubic meters of bedrock were excavated. Removing that volume required organized labor, coordinated effort, and sustained oversight. Such engineering implies a governing authority capable of mobilizing workers on a significant scale.

5. Location protects access to sacred precincts.

The separation lies directly south of the Temple Mount plateau. In antiquity, this elevated zone likely housed religious and administrative functions central to Jerusalem’s authority. By isolating the southeastern ridge, the carved barrier shielded approaches to this area.

Control over movement between these elevations would have strengthened centralized power. Access could be funneled through specific entry points rather than left exposed. The configuration suggests an integrated defensive strategy rather than ad hoc construction.

6. Excavations involved leading Israeli institutions.

The feature was documented during systematic excavations conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority in collaboration with researchers affiliated with Tel Aviv University. Field teams carefully removed centuries of debris before mapping the full extent of the structure.

Geological specialists assessed the limestone composition and fracture patterns. Their analysis confirmed that the vertical faces and consistent depth were the result of human activity. The interdisciplinary approach strengthened confidence in interpretation.

7. Quarry theory fails under structural analysis.

Some critics initially proposed that the cut bedrock represented an ancient quarry later repurposed. However, its alignment along the ridge boundary and its consistent depth undermine that explanation. Typical quarry scars follow material extraction patterns rather than defensive lines.

This feature tracks precisely along a natural topographic vulnerability. Its form aligns with fortification logic rather than resource removal. The evidence suggests it was conceived as a boundary from the outset.

8. Urban planning appears earlier than assumed.

Minimalist historical models once portrayed tenth century BCE Jerusalem as a small settlement lacking monumental architecture. The scale of this rock cut boundary challenges that perspective. Large scale excavation requires not only manpower but also administrative coordination.

Such planning implies taxation, labor organization, and centralized leadership. Even if one avoids direct identification with specific biblical figures, the infrastructure itself indicates early urban sophistication.

9. Defensive systems likely extended beyond it.

Archaeologists have previously uncovered massive walls, towers, and fortifications within the City of David and Ophel areas. The carved boundary appears integrated into this broader defensive network.

Ongoing excavations seek to identify connected gate complexes and retaining structures. Preliminary alignments suggest controlled passageways once linked the separated ridges. The configuration resembles strategic fortification rather than isolated construction.

10. Debate continues over historical implications.

The discovery has intensified discussions between scholars who emphasize textual tradition and those who approach the Bible as later literature. Some argue the physical evidence supports early state formation in Jerusalem. Others caution against direct correlation.

What remains undisputed is the scale of the engineering. Beneath the southeastern ridge lies a carved boundary that forces historians to reconsider how organized Jerusalem was three thousand years ago. The stone itself now anchors that debate in measurable form.