The numbers were not what anyone expected.

For years, astronomers pointed their instruments toward a seemingly unremarkable patch of sky, a region chosen precisely because it appeared empty. It was meant to serve as a control, a baseline for understanding what lies beyond the visible. Instead, the latest ultra deep observation delivered something far more complicated. Patterns began to emerge where quiet was expected. Faint signatures clustered in ways that raised new questions. The deeper the data was processed, the less simple the darkness appeared.

1. Webb’s deep field revealed thousands of ancient galaxies.

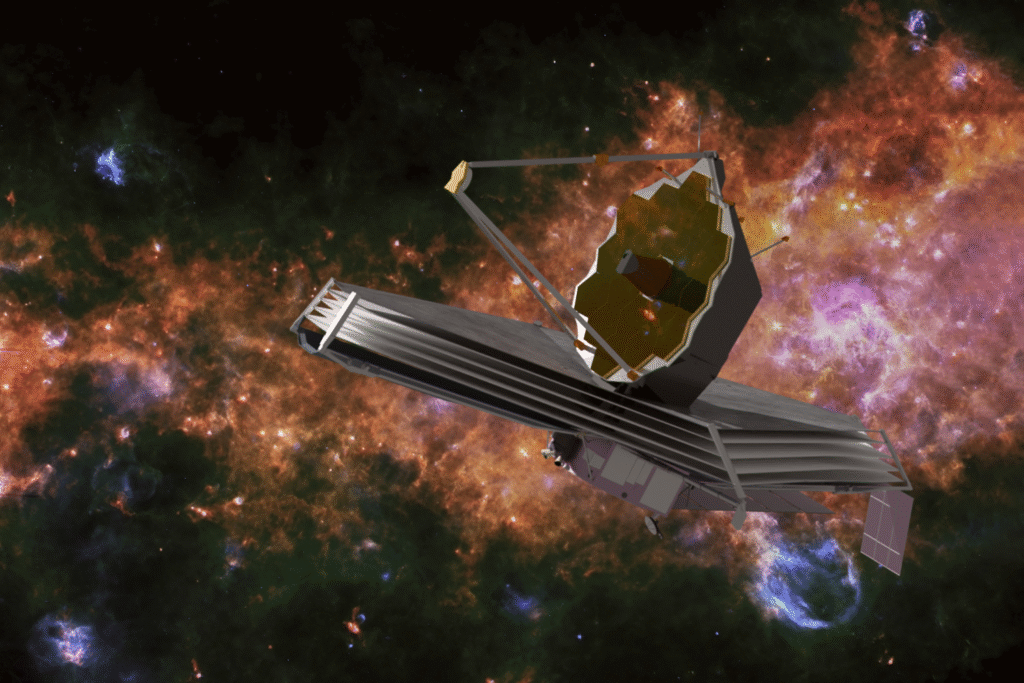

The JWST’s observation of the GOODS-South region, known as the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES), captured thousands of faint galaxies and compact objects stretching back more than 13 billion years, according to NASA’s 2024 release on JADES. Each of these light points represents a window into the early universe, some formed just 400 million years after the Big Bang. The telescope’s infrared sensitivity revealed details that earlier missions, including Hubble, could not detect, opening the door to identifying objects that may conceal early black holes.

2. Over one thousand possible black holes were identified in the field.

Analysis of the JADES and CEERS deep-field data revealed more than a thousand potential black-hole candidates, as stated by a 2024 study from the University of Texas at Austin’s Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) team. These candidates show infrared signatures of active galactic nuclei—regions powered by supermassive black holes consuming gas. That density far exceeds previous predictions, suggesting that black holes emerged and grew faster than expected in the early universe, according to the CEERS findings.

3. The discovery challenges long-held models of early black-hole growth.

Researchers from the Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics reported that these early black holes, some only a few hundred million years old, appear more massive than existing models can explain. Such growth implies they formed from unusually large “seed” black holes or through rapid accretion in gas-rich environments. The discovery means that black holes weren’t rare exceptions of cosmic evolution but key players in shaping the first galaxies, as discovered by the Kavli Institute’s 2024 analysis of JWST data.

4. Webb’s infrared vision reveals black holes hidden behind cosmic dust.

Because JWST observes primarily in infrared wavelengths, it can penetrate dust that hides visible-light emissions. Many of these black-hole candidates are buried within dusty galaxies where optical telescopes would see nothing at all. The deep-field data show that the earliest galaxies were far dustier than anticipated, hinting that rapid star formation and black-hole feeding often went hand-in-hand.

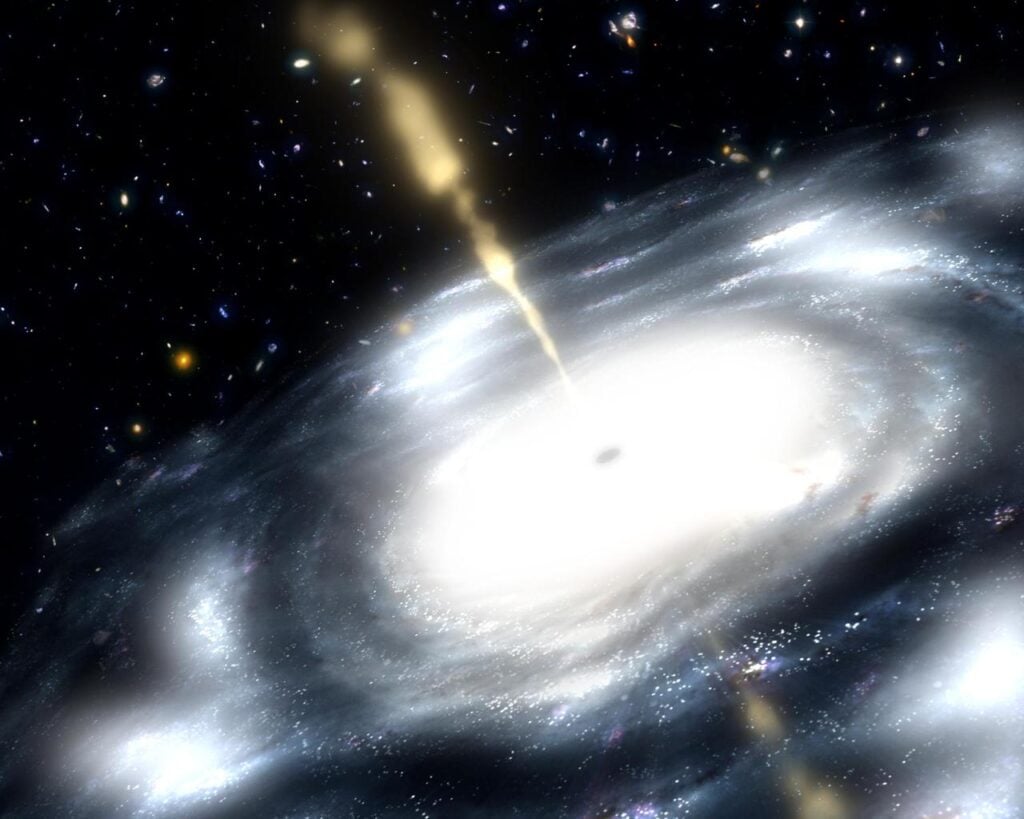

5. Compact red objects hint at powerful ancient activity.

The faint, compact, red sources scattered throughout the JADES and CEERS fields have become the most intriguing targets. Their redness comes partly from their extreme distance—light stretched by cosmic expansion—and partly from obscuring dust heated by active black holes. These subtle red dots now appear to be early galactic cores where black holes first ignited, turning quiet galaxies into luminous powerhouses of the young universe.

6. The number density of these black holes exceeds expectations.

Models based on older telescope data suggested that only a few early galaxies should host actively feeding black holes. Yet Webb’s deep field shows several times more than anticipated. The numbers imply that the conditions for black-hole birth and growth were common in the first billion years after the Big Bang, making these objects central to early cosmic evolution rather than rare anomalies.

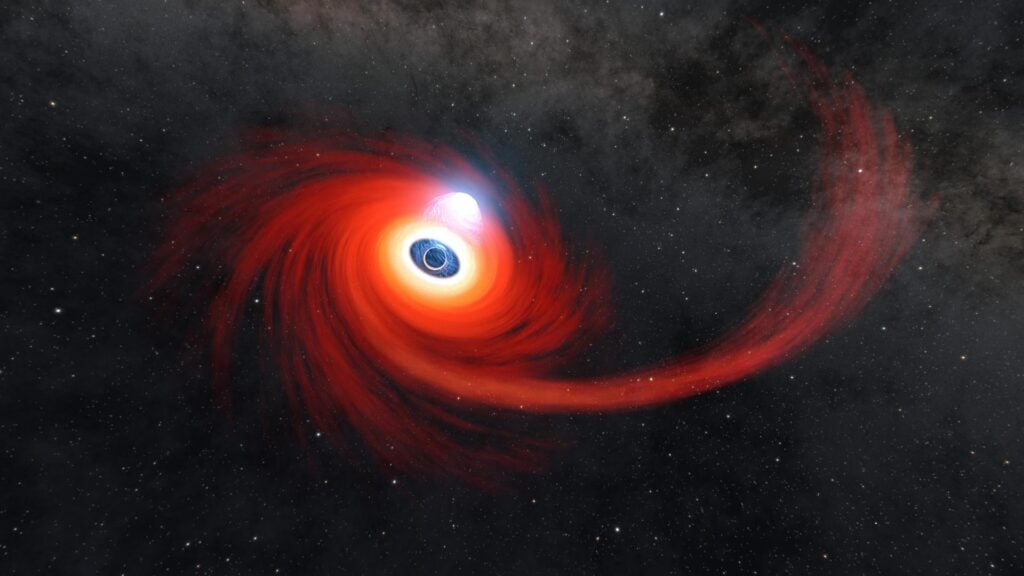

7. These findings redefine how galaxies and black holes co-evolved.

Astronomers have long believed that galaxies and their central black holes grow together. With so many early examples now visible, it seems black holes may have shaped their galaxies earlier than assumed. Their gravitational pull and radiation could have influenced star formation, regulating how galaxies matured. The discovery reframes black holes not as destructive forces but as architects of structure in the universe’s infancy.

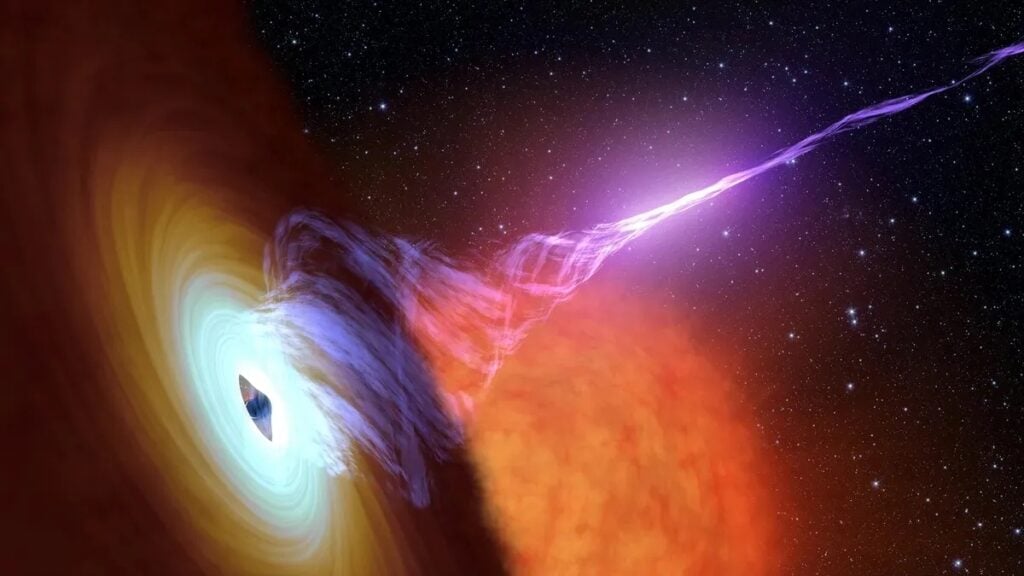

8. Future Webb spectroscopy will confirm which candidates are real.

Imaging alone cannot confirm every source as a black hole. Scientists are now planning deep spectroscopic studies using JWST’s NIRSpec and MIRI instruments to measure emission lines that reveal gas swirling near event horizons. Those spectra will confirm masses, feeding rates and distances. Each confirmed detection will help narrow theories about when, where and how black holes first came to dominate galactic centers.

9. The results reshape estimates of the early universe’s hidden mass.

If hundreds or even thousands of early black holes existed, their combined mass would make up a significant fraction of the universe’s total matter during its first billion years. That would mean the early cosmos was far more energetic and dynamic than expected. With Webb’s unprecedented depth, astronomers are now beginning to piece together a clearer picture of just how quickly the universe built its darkest giants.