Extreme drought and new culling laws put kangaroos at the center of Australia’s survival struggle.

The story of kangaroos in Australia has never been straightforward. For some, they are symbols of the continent, bounding across postcards and tourism ads. For farmers, they are competitors for grass and water, especially in regions where every blade of pasture matters. That conflict has only sharpened in recent years as droughts kill millions naturally, while governments debate new legislation to make killing them easier.

The contrast is jarring. In 2019, during one of Australia’s harshest droughts in decades, reports described paddocks strewn with carcasses as kangaroos starved or collapsed from thirst. Now, instead of relief, new policies are expanding commercial culling quotas. The country is faced with a paradox—kangaroos are dying in staggering numbers, yet lawmakers argue that more killing is the solution.

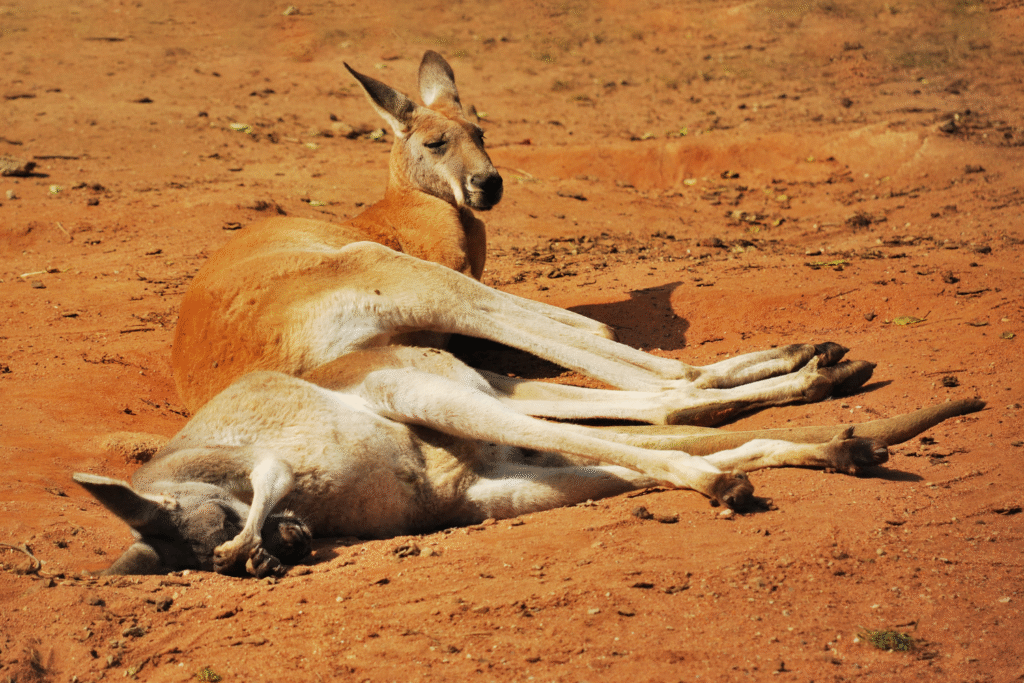

1. The 2019 drought left kangaroos dying in plain sight.

Across New South Wales and Queensland, the 2019 drought stripped landscapes of grass and water. Farmers reported mobs of kangaroos collapsing near dams and fences, their bones visible through thinning skin. The Guardian documented mass die-offs, with estimates suggesting millions perished during that single dry period.

Those images shocked even Australians used to harsh cycles of climate. Yet within months, the conversation pivoted. Instead of focusing on survival, debates shifted to what rising kangaroo deaths meant for farm viability and livestock grazing. The haunting picture of empty paddocks full of carcasses became background noise in a much larger political fight.

2. New legislation is pushing for more culling, not less.

Rather than slowing hunts, recent proposals have expanded commercial shooting quotas, citing overabundance and agricultural damage. State governments in New South Wales and Victoria have both endorsed higher limits, framing kangaroos as environmental stressors when food runs scarce. These quotas are now being codified into law, as reported by ABC News.

That move has drawn sharp criticism from animal welfare groups, who argue the policies ignore drought-driven mortality. To them, counting starving kangaroos as part of “overpopulation” skews reality. Yet politicians point to pressures on rural voters, making legislative expansion of culling a politically safe, if ethically messy, choice.

3. Conservationists warn the math doesn’t add up.

Biologists argue that government population surveys, used to justify high quotas, fail to capture the true toll of drought. A report from the University of Sydney highlighted how aerial counts can overestimate numbers, particularly in years following die-offs. Critics say this means kangaroos could be culled at unsustainable levels, effectively doubling the impact of climate disasters already killing them.

This isn’t just a scientific squabble—it’s a survival calculation. If policies keep inflating population estimates while droughts escalate, Australia risks hollowing out its kangaroo populations under the banner of management. Conservationists caution that treating mass deaths and culls as separate events is the fastest way to erase species stability.

4. Farmers argue their livelihoods can’t wait for nuance.

For graziers running cattle or sheep, the competition is direct. Kangaroos eat pasture, drink scarce water, and in extreme years can strip land bare. Rural lobbyists insist that without culling, entire farm businesses collapse, particularly during back-to-back droughts.

This tension fuels the sharpest political divide. Urban Australians often see kangaroos as untouchable wildlife, while rural voters frame them as pests that bankrupt families. When resources vanish, farmers say decisions can’t wait for long-term conservation science—they’re made in the moment, with whatever relief politics will allow.

5. Kangaroos themselves show no mercy to the weakest.

In starving mobs, larger males outcompete smaller kangaroos for dwindling food. Juveniles and females often succumb first, leaving fields littered with bodies long before adults falter. This harsh natural order reinforces the argument that human intervention is inevitable—though not everyone agrees on what intervention should look like.

It’s a reminder that drought doesn’t simply cause slow, silent deaths. It rewrites group dynamics, amplifying stress and accelerating collapse. For observers, it can look brutal, but in ecosystems under climate strain, even iconic animals follow survival rules that leave the weakest behind.

6. The international market for kangaroo meat complicates the debate.

Australia doesn’t just cull for population management—it exports kangaroo meat and leather to dozens of countries. That market provides a financial incentive for governments to maintain high quotas, keeping rural economies tied to commercial harvesting. Critics say this shifts the framing of culls from conservation to profit.

For wildlife groups, this is the crux of the problem: if kangaroos are both cultural icons and commodities, how can their treatment ever reflect ecological balance? The global demand ensures kangaroo killing is not just about survival but about trade, muddying every conservation argument that follows.

7. Animal welfare groups call the killing methods inhumane.

Groups like RSPCA Australia have raised concerns over how kangaroos are shot and processed, with claims that dependent joeys are often left to die after mothers are killed. These accusations stir public outrage, particularly among city dwellers who rarely see kangaroos as pests.

For governments, defending quotas while also confronting welfare concerns creates a political balancing act. The industry maintains it follows strict codes of practice. But videos circulated online show disturbing scenes that make the debate about more than numbers. It becomes a question of what humane management looks like in practice.

8. Climate projections show droughts will only intensify.

Meteorological agencies warn that Australia’s climate will grow hotter and drier, with drought cycles lengthening. This makes the 2019 mass deaths a preview, not an anomaly. Kangaroos, already vulnerable to heat stress and water scarcity, face compounding threats as droughts collide with expanded hunting quotas.

The implications stretch beyond kangaroos. If droughts undermine kangaroo populations while policies accelerate kills, other wildlife dependent on the same ecosystems face ripple effects. The entire fabric of grassland ecology begins to thin. Managing kangaroos, then, becomes a proxy for how Australia will manage survival in a harsher climate.

9. Aboriginal communities push for different management models.

Some Indigenous groups argue kangaroo stewardship should follow cultural practices, not just quotas. Traditional methods often balanced harvest with ecological observation, treating kangaroos as kin rather than competitors. Today, those voices push back against commercial frameworks, calling for management systems that respect both ecology and cultural heritage.

Incorporating Indigenous knowledge could change the shape of the debate. It shifts the lens from eradication to balance, offering models that don’t treat mass culling as inevitable. While these approaches aren’t yet mainstream policy, they highlight alternatives that move beyond the binary of kill-or-protect.

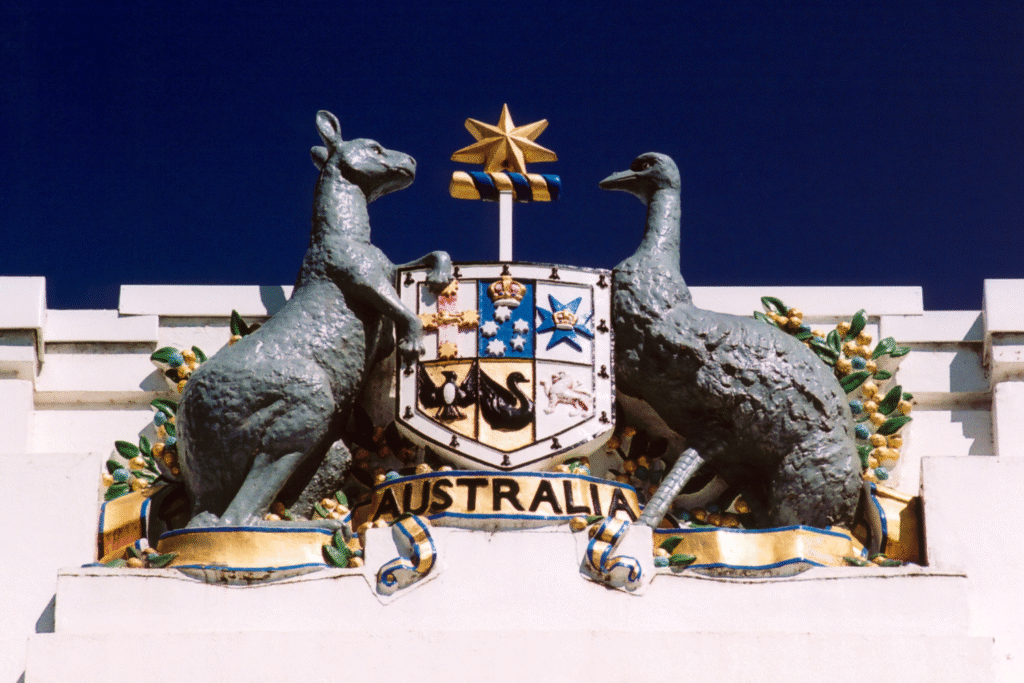

10. The national symbol is caught in a contradiction.

The kangaroo sits on Australia’s coat of arms, fronting tourism ads and international branding. Yet it’s also treated as a pest, subject to industrial-scale killing. That contradiction fuels emotional arguments on both sides, turning kangaroo policy into a cultural fault line as much as an ecological one.

Whether kangaroos survive future droughts depends less on symbolic value than on political will. The question isn’t only how many will die from thirst or bullets, but what kind of story Australians want their national animal to tell the world—resilience in crisis or expendability under pressure.