Ancient rocky swarms around Jupiter now in focus.

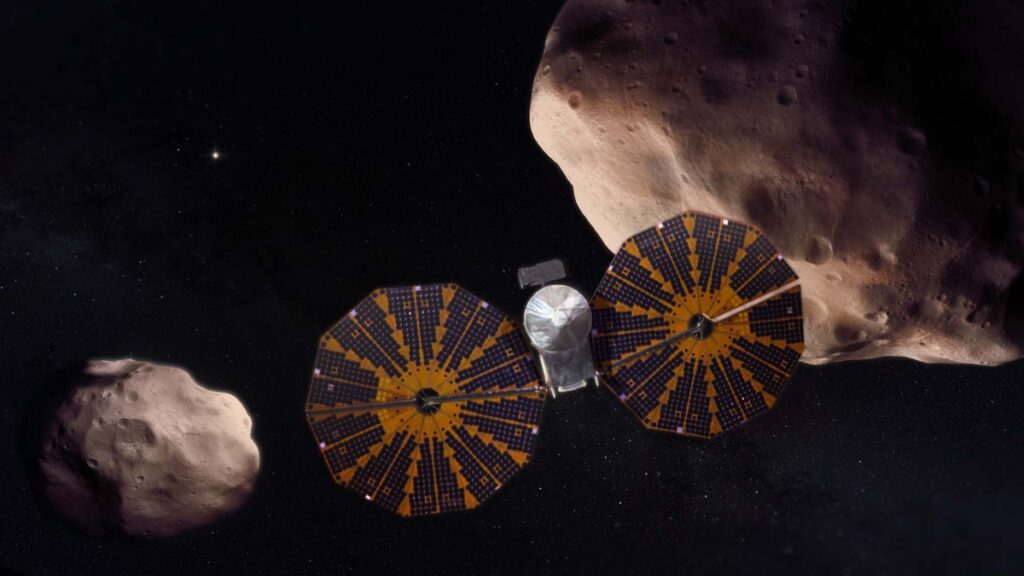

The Lucy mission has begun returning images of the elusive swarms of asteroids orbiting in tandem with Jupiter—and those pictures are changing our understanding of early solar-system relics. These “Trojan” asteroids, locked in Jupiter’s path ahead of and behind the planet, are thought to contain untouched material from the dawn of the solar system. With each high-resolution image Lucy beams back, scientists are peeling back billions of years of history frozen in these wandering remnants. The story unfolding is both scientific and strangely poetic—a glimpse of planetary building blocks caught mid-orbit.

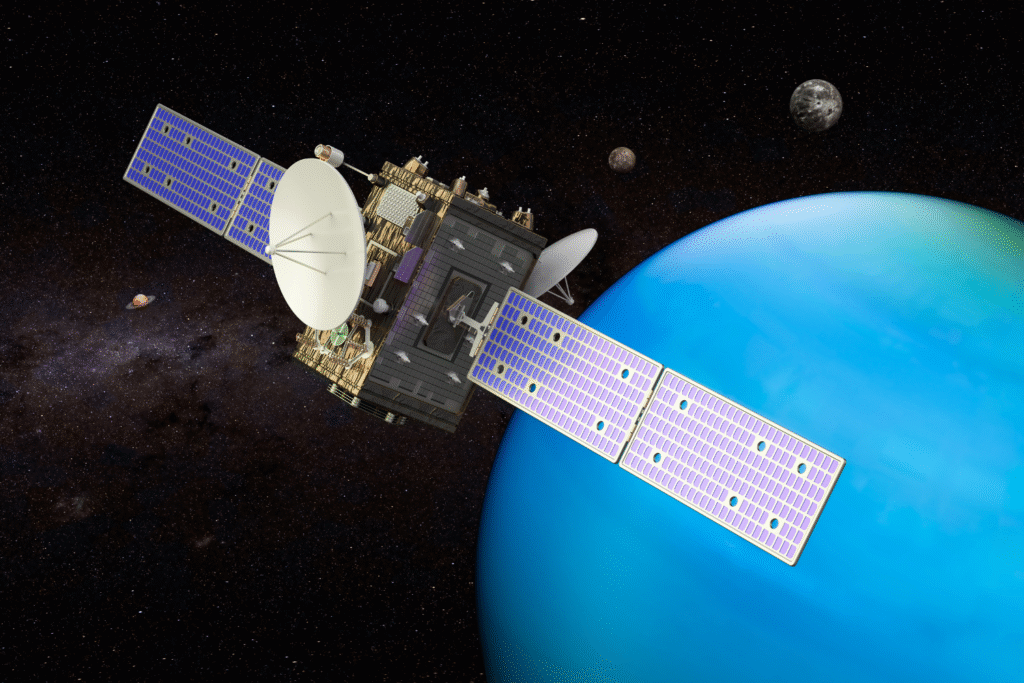

1. Lucy captured its first detailed images of Trojan asteroids in early 2023.

Between March 25 and 27, 2023, NASA’s Lucy spacecraft used its L’LORRI imager to capture its first calibration images of four Trojan asteroids—Eurybates, Polymele, Leucus and Orus—while they were more than 330 million miles from Earth, as reported by NASA. The photos weren’t just visual milestones; they confirmed Lucy’s optics, navigation, and camera precision. Engineers analyzed the faint light reflected from these asteroids to refine trajectory plans for future close fly-bys. It was the first time we’d seen the Trojan targets through Lucy’s own instruments, marking the real beginning of its science mission.

2. The new images show the Trojans’ surfaces are dark and ancient.

Spectral data from the returned imagery revealed the asteroids are coated with carbon-rich compounds, similar to primitive C-type asteroids in the outer belt. That darkness isn’t just dust—it’s chemistry dating back 4.5 billion years. The low reflectivity indicates minimal alteration since formation, suggesting these bodies avoided major impacts or melting events. NASA’s planetary scientists interpret these results as direct evidence that Trojans preserve the original material from the solar nebula, offering a window into planetary birth. Each image confirms that what Lucy is chasing are time capsules older than any rock on Earth, according to NASA’s 2024 analysis.

3. Lucy will visit eight Trojans to compare their chemistry and structure.

The mission’s official plan, outlined by the Southwest Research Institute which leads Lucy’s science team, lists eight Trojans for detailed fly-bys between 2027 and 2033. These include both the leading “Greek camp” and trailing “Trojan camp,” allowing scientists to examine regional differences in origin and evolution. Comparing composition, rotation, and surface damage across this diverse group could reveal whether these asteroids formed together or were captured separately by Jupiter’s gravity. The SwRI team notes this will be the most comprehensive Trojan survey ever attempted, bridging gaps between planetary science, chemistry, and celestial mechanics.

4. Some of the early images already reveal craters, ridges and irregular shapes.

Even from hundreds of millions of miles away, Lucy’s cameras have detected faint topographic variations on these distant worlds. The uneven silhouettes and pockmarked surfaces imply long histories of bombardment and internal stress. Those details hint at how these bodies have weathered eons of collisions without fragmenting entirely. As Lucy approaches its targets over the next few years, the resolution will sharpen, turning these rough outlines into maps that capture the scars of the solar system’s earliest violence.

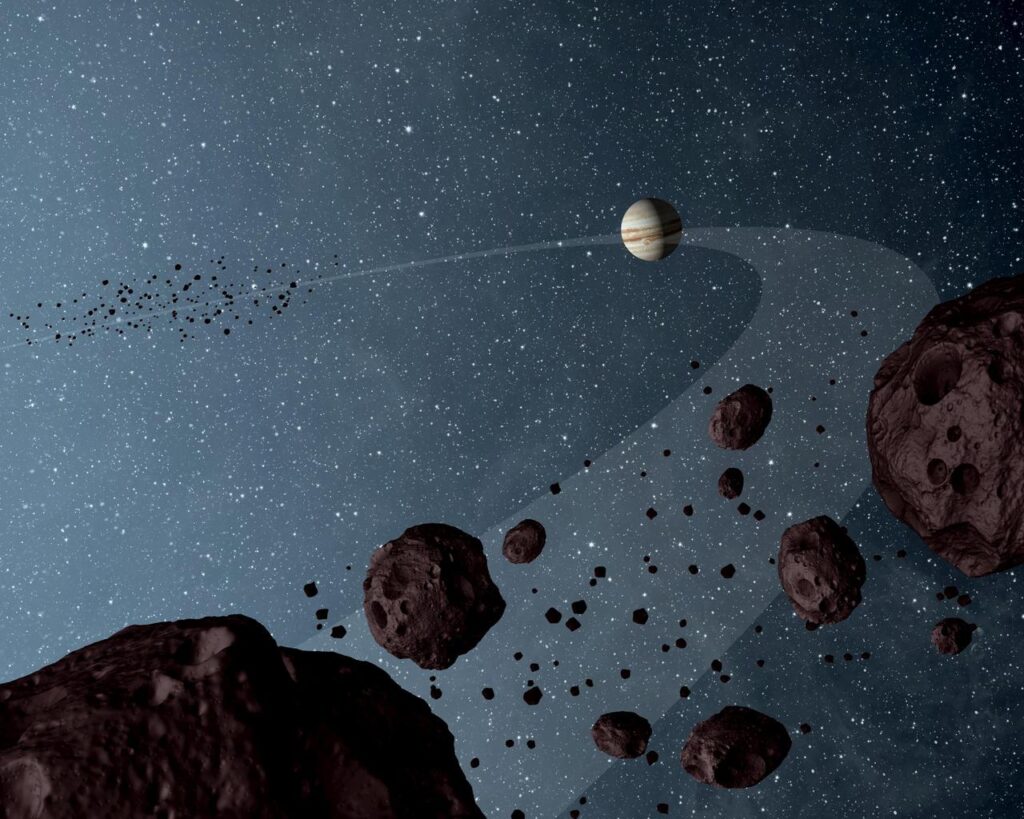

5. The Trojan asteroids travel in two massive swarms orbiting with Jupiter.

Trojans are unique because they occupy stable Lagrange points—one cluster ahead of Jupiter and another trailing behind. Lucy’s looping trajectory will allow it to visit both regions, something no spacecraft has done before. Each swarm might hold slightly different histories of capture or composition, and comparing the two will give scientists clues about how Jupiter’s gravity shaped the early solar system. The mission’s dual-swarm design effectively doubles its potential for discovery, allowing it to contrast two snapshots of the same cosmic neighborhood.

6. Lucy’s instruments are tuned for faint light and distant darkness.

Because Trojan asteroids reflect so little sunlight, Lucy’s cameras and spectrometers must be incredibly sensitive. The L’LORRI instrument was designed to handle low-light conditions, while the L’TES thermal spectrometer measures heat patterns to infer composition. Together, they can capture meaningful data even when the asteroids are little more than shadowy outlines in space. That design gives scientists confidence that, as Lucy draws nearer, its images will capture fine details that would otherwise be lost in the dark.

7. The mission could redefine how scientists view early planet formation.

The Trojans’ makeup and distribution are clues to how materials were shuffled during the solar system’s chaotic youth. If the objects show compositional differences, it may confirm that Jupiter migrated after formation, pulling in material from multiple regions. If they’re similar, it suggests the solar nebula mixed more evenly than expected. Either way, the results will adjust models of how Earth and its neighbors came to be, deepening our grasp of the cosmic past written into these stones.

8. Close fly-bys from 2027 onward will reveal every detail of the Trojan worlds.

Lucy’s upcoming encounters will bring it within a few hundred kilometers of its targets. From that distance, scientists expect to see surface fractures, boulders, and mineral patterns never observed before. Those passes will convert light points into complex worlds, revealing the kind of geological diversity usually reserved for planetary missions. Each fly-by will add a new piece to the puzzle, showing how these bodies evolved and interacted with Jupiter’s gravitational pull across billions of years.

9. Data from Lucy’s Trojan observations will guide future asteroid exploration missions.

Beyond enriching planetary science, Lucy’s findings will help engineers plan how to approach fragile, low-gravity bodies for future research or defense. Understanding their composition and structural strength is crucial for predicting how asteroids react to impacts or deflection attempts. The mission’s imaging and spectral data will become a reference library for small-body studies—practical science spun from the pursuit of ancient cosmic history.