What archaeologists uncovered had been waiting undisturbed.

For centuries, the ground in Belize kept its secret without disturbance, erosion, or rumor. The chamber lay sealed through the rise and fall of civilizations, untouched by looters, weather, or chance. When researchers finally reached the tomb, they expected fragments, loss, or absence. Instead, they found something deliberately placed and carefully preserved, its color unchanged by time. The discovery suggested intention, power, and belief strong enough to survive thousands of years underground. What emerged was not just an object, but evidence of how permanence was once imagined, built, and trusted to outlast memory itself.

1. The burial may belong to the ruler who founded Caracol.

The burial may belong to the ruler who founded Caracol.

Researchers suggest the tomb could belong to Te K’ab Chaak, the king credited with establishing Caracol’s ruling dynasty in the early fourth century A.D. The ceramics and construction layers place the burial firmly within the Early Classic era. According to the Chases, who have excavated the site for decades, the chamber’s location and grave goods fit what is expected of a founding ruler. Even so, no surviving inscriptions name the individual directly. Without that confirmation, the attribution remains a carefully supported hypothesis rather than a settled fact.

2. The tomb sat undisturbed for more than 1500 years.

No signs of looting or disturbance appeared in the chamber they reached. Its sealed nature preserved delicate objects, jade, shells, and ceramics, exactly where they were placed. That context is extremely rare in Maya archaeology, and it gives scholars a cleaner view of burial practice and long-distance trade networks.

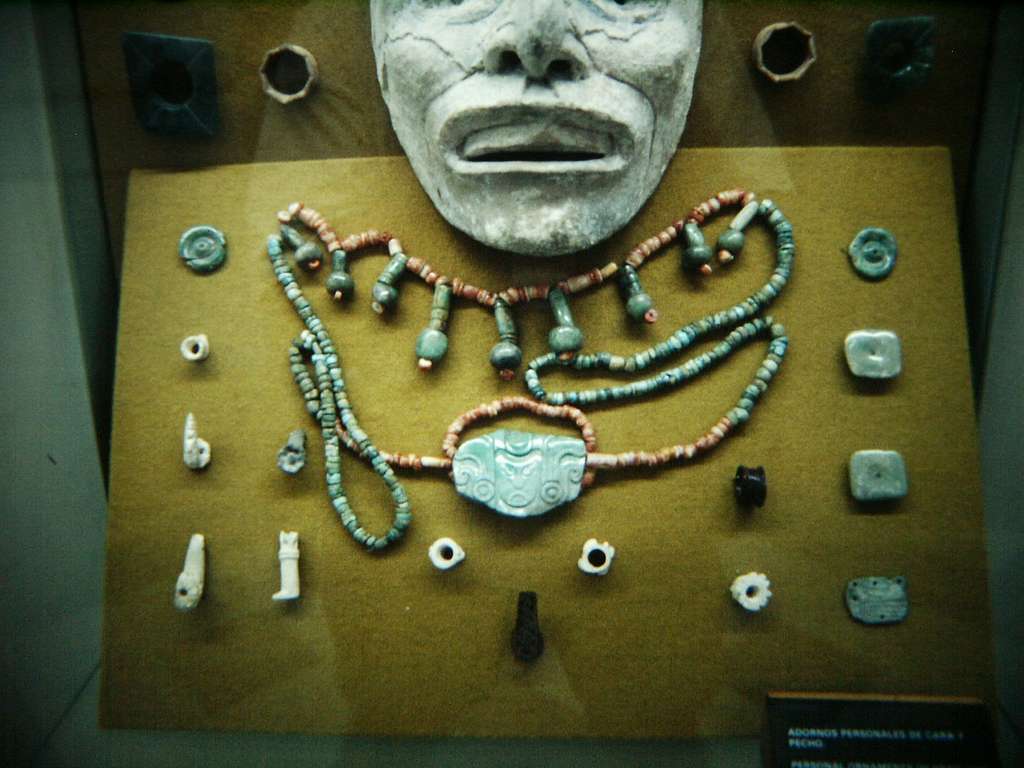

3. Multiple sets of jade earflares and jewelry fill the chamber.

Inside, the team found three distinct sets of jade ear ornaments, an unusual quantity for a single individual. As stated by artifacts cataloging, such redundancy suggests elite display, ritual exchange, or dynastic symbolism. The quantity opens a fresh lens on how status was communicated in early Maya courts.

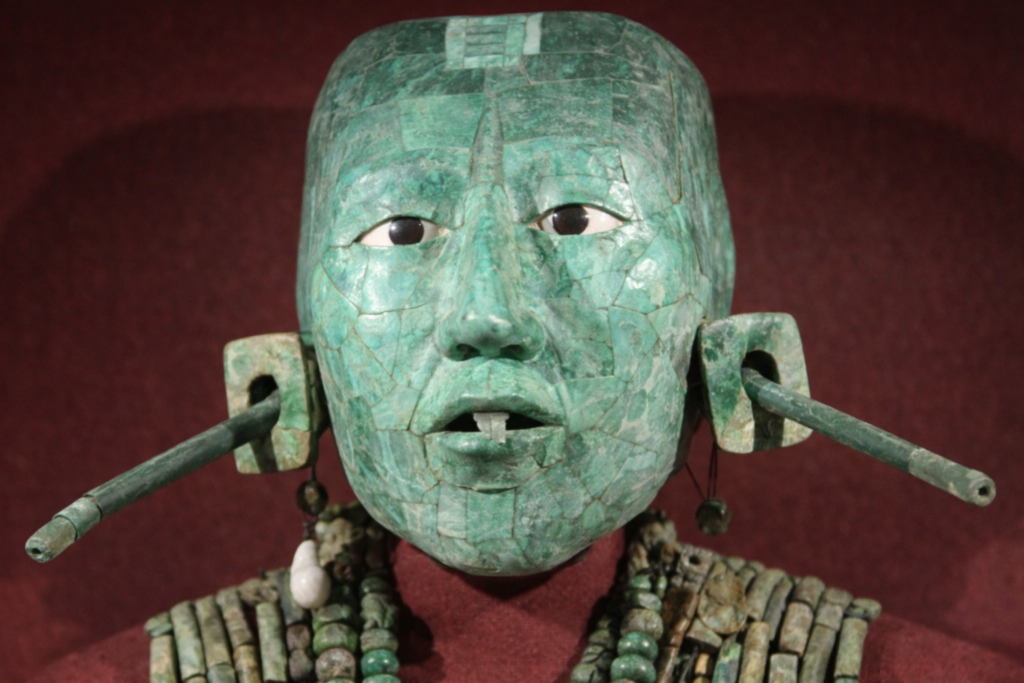

4. A jadeite mosaic death mask was shattered yet intact in aggregate.

Fragments of a mosaic mask made from jadeite were present, lying in their original scatter rather than removed. The artisans likely intended it to encase the face of the deceased, symbolically binding life and afterlife. Because the pieces remain in situ, reconstruction may reveal iconographic details about the individual or the cosmology he subscribed to.

5. Pottery vessels depict gods, captives, and offerings.

Among the ceramics, researchers identified one vessel with a Maya ruler receiving tribute, another painted with Ek Chuah, the Maya god of commerce. These iconographic cues hint that the buried person played roles in both governance and trade. The scenes also reflect ideological claims he likely made during his rule, embedding religion into his public persona.

6. Tubular jade beads show carved spider-monkey faces.

Four jade beads carved with both living and skeletal spider-monkey faces were found, a motif with layered symbolism—tying life, death, transformation, or ancestors. Their inclusion suggests that ritual meaning extended to even small decorative elements in the tomb. These beads connect to both art and the personal beliefs of the interred ruler.

7. Red cinnabar stained parts of the tomb walls.

The walls of the chamber bore a coating of cinnabar, a red mercury sulfide pigment often used in elite Maya burials. The color red in many Mesoamerican cultures is tied to blood, life force, and sacredness. The use of cinnabar adds ritual gravity to the tomb, emphasizing that this was no ordinary internment.

8. A secondary cremation sits just above the tomb.

Stratigraphic evidence shows that a cremation burial from the same era was interred above this chamber. That layering indicates complex burial relationships and perhaps layered ritual usage in this acropolis. It also helps bracket the dating of the royal tomb and hints at connections to broader regional mortuary practices.

9. The tomb challenges the timing of Maya-Teotihuacan influence.

Because the burial dates roughly to A.D. 330–350, it pushes the possibility that interactions with Teotihuacán were occurring earlier than previously thought. Some artifacts and mortuary practices in nearby burials hint at central Mexican influence. If confirmed, this tomb may reshape models of Mesoamerican interregional exchange.

10. The find may reset dynastic history at Caracol.

This is the first time an identified royal tomb has been found at Caracol. By anchoring a physical burial to the early dynastic period, researchers can better align inscriptions, monument building, and the city’s political evolution. As excavation continues and lab analyses (isotope, DNA) proceed, this tomb could become a foundational reference for Maya royal archaeology.