The mountain remembers what it once did.

For years, the crater sat under drifting clouds, giving no outward sign that anything restless lived beneath it. Locals farmed nearby hills, children walked to school, and the lake inside the summit reflected a sky that looked perfectly calm. Now instruments are detecting subtle changes that scientists cannot dismiss. Nothing dramatic has happened yet. That is what makes the tension heavier. The last time this volcano gave small warnings, the consequences reached far beyond its valley.

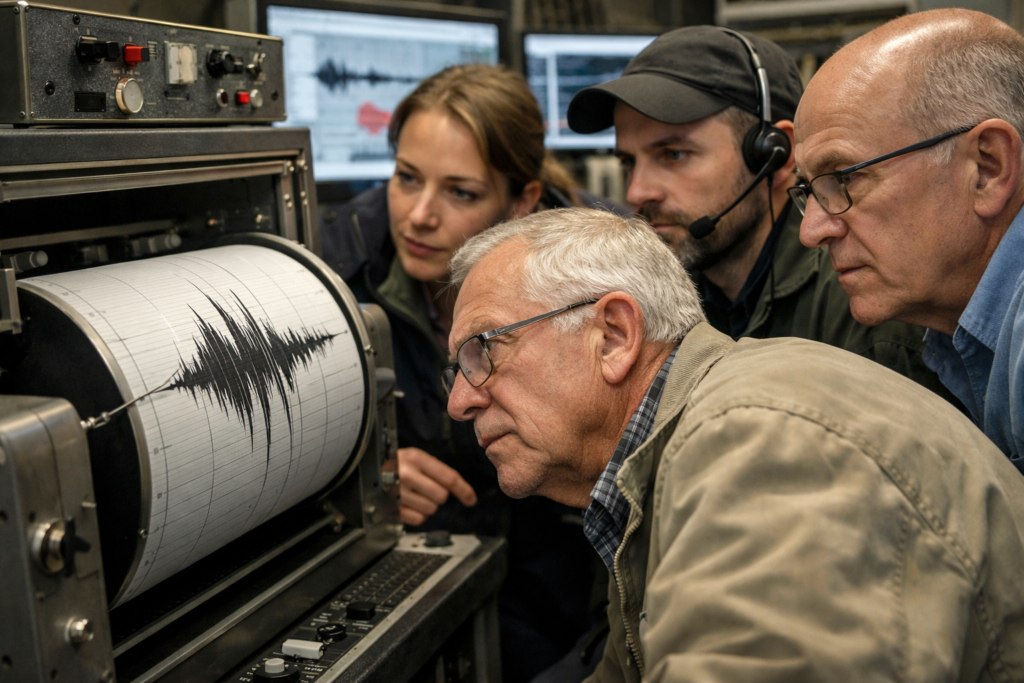

1. Seismic networks record unusual shallow earthquake swarms.

Monitoring stations operated by Mexico’s National Center for Disaster Prevention have recently detected clusters of low magnitude earthquakes beneath El Chichón in Chiapas. These tremors are shallow and concentrated directly below the crater rather than scattered regionally.

El Chichón sits about 35 kilometers northwest of Pichucalco in northwestern Chiapas. In early 1982, similar seismic swarms preceded three explosive eruptions. Scientists now compare current seismic signatures with archived data from that period, searching for patterns that could signal magma movement at depth.

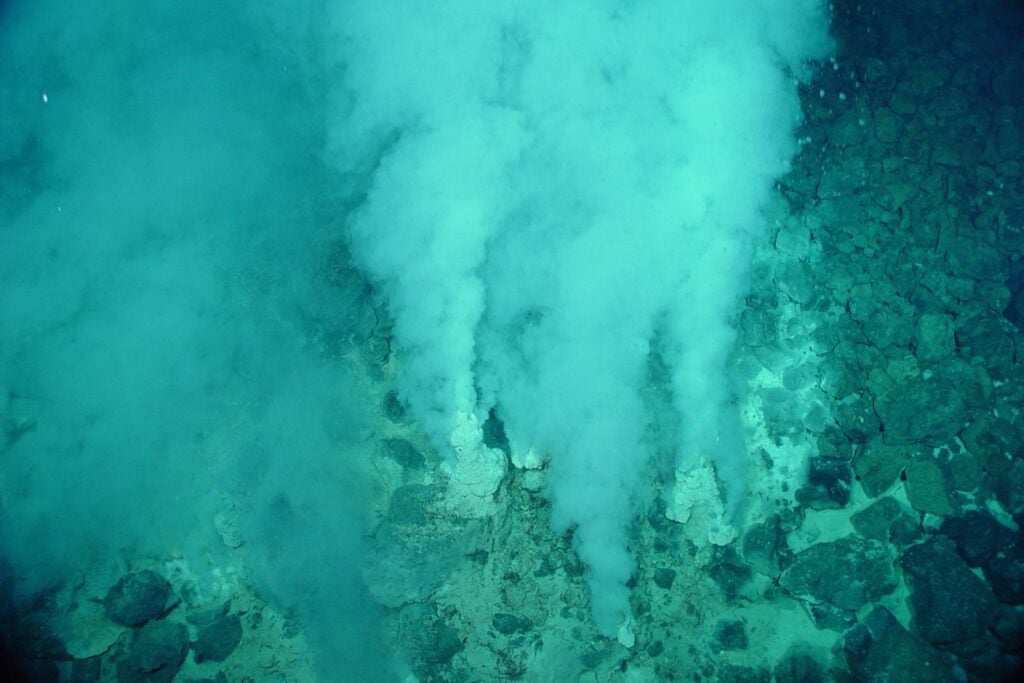

2. Gas ratios begin shifting within crater emissions.

Researchers collecting gas samples around the crater lake have documented measurable fluctuations in sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide output. These gases escape through fumaroles along the crater walls, where changes can signal deeper thermal shifts.

After the 1982 eruption, a crater lake formed in the newly blasted summit. Today that lake partially traps volcanic gases, complicating interpretation. Scientists from the National Autonomous University of Mexico monitor chemical ratios closely, because rising sulfur dioxide often correlates with magma approaching the surface.

3. The 1982 eruption reshaped the region permanently.

On March 28 and April 3, 1982, El Chichón produced explosive eruptions that destroyed nine villages including Francisco León. Ash columns reached over 20 kilometers into the atmosphere, injecting sulfur aerosols globally.

More than two thousand people died, and thousands were displaced across Chiapas and Tabasco. The eruption formed a one kilometer wide crater and altered regional climate temporarily by reducing global temperatures. That history frames every new tremor with uncomfortable memory for nearby communities.

4. Ash fallout once circled the planet.

Satellite observations in 1982 tracked sulfur dioxide clouds from El Chichón spreading across the Northern Hemisphere. The eruption released roughly seven million tons of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere.

That volume rivaled major twentieth century eruptions, influencing atmospheric circulation and causing measurable cooling for months. Volcanologists now evaluate whether current degassing trends resemble early stages of that event, aware that El Chichón has demonstrated capacity for global atmospheric impact before.

5. Nearby communities live within evacuation zones.

Towns such as Chapultenango and surrounding rural settlements lie within established hazard maps. Authorities have developed contingency plans based on the 1982 disaster, though infrastructure remains limited in mountainous terrain.

Civil Protection officials conduct periodic drills, but evacuation routes depend on narrow roads vulnerable to ashfall and landslides. Renewed activity increases pressure on local governments to balance transparency with caution, avoiding panic while acknowledging potential risk to thousands.

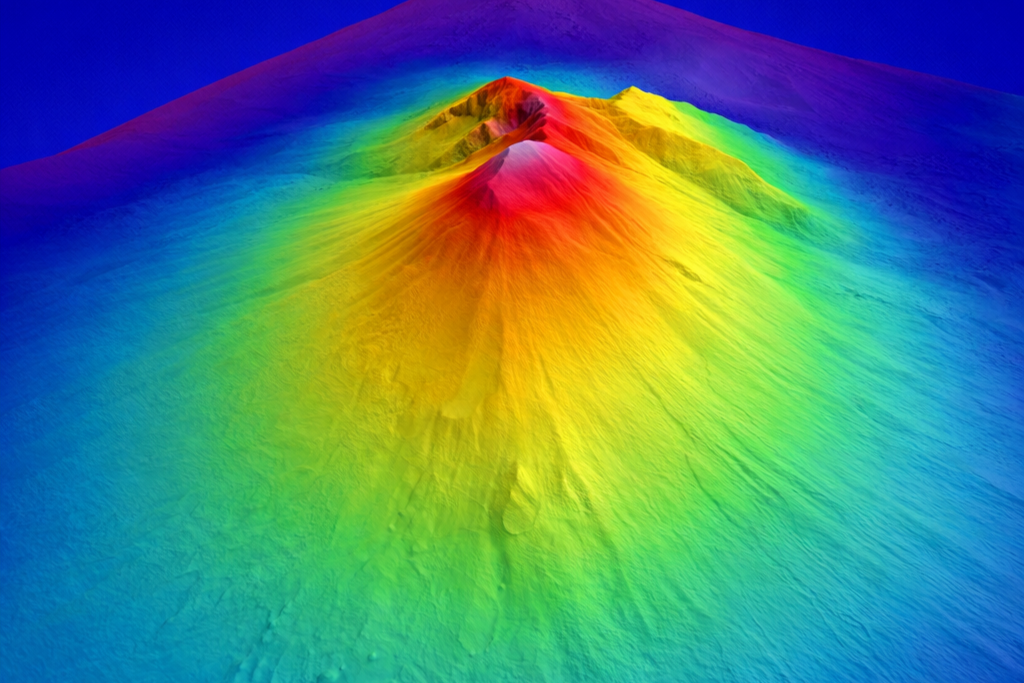

6. The volcano sits on a volatile tectonic boundary.

El Chichón lies within the Chiapanecan volcanic arc, influenced by the subduction of the Cocos Plate beneath the North American Plate. This tectonic setting fuels magma generation deep below southern Mexico.

Unlike towering stratovolcanoes along the Trans Mexican Volcanic Belt, El Chichón is smaller but chemically explosive due to high sulfur content. Its magma composition contributed to the violence of 1982. Understanding tectonic context remains central to assessing renewed unrest.

7. Hydrothermal systems complicate eruption forecasting.

The crater lake and hydrothermal vents create additional uncertainty. Heated groundwater can produce phreatic explosions without new magma reaching the surface, making surface calm deceptive.

Scientists must distinguish between steam driven disturbances and deeper magmatic ascent. Changes in lake temperature, acidity, and water level are monitored closely. Small variations can signal instability beneath the water column, where pressure builds unseen.

8. Satellite thermal imaging shows subtle heat anomalies.

Recent satellite data have detected minor thermal variations near the summit compared to long term averages. These anomalies remain modest but persistent over several monitoring cycles.

Thermal changes can indicate increased gas flux or rising magma at depth. Remote sensing allows researchers to track patterns without constant physical presence on unstable slopes. Interpreting these signals requires caution, yet consistency draws scientific attention.

9. Regional memory shapes public response today.

Residents who remember 1982 recount ashfall turning daylight to darkness and livestock suffocating. Oral histories circulate widely in communities around Pichucalco and Francisco León.

That memory influences how new information spreads. Even minor tremors prompt concern because earlier warnings were initially underestimated. Authorities must communicate carefully, aware that fear is grounded in lived experience rather than speculation.

10. Scientists debate whether unrest signals escalation.

Current activity does not guarantee eruption, yet comparisons to early 1982 data keep researchers alert. The pattern remains incomplete, neither definitively escalating nor fully stable.

Volcanologists analyze seismic frequency, gas chemistry, and deformation measurements together. No single indicator determines outcome. What is clear is that El Chichón is no longer entirely dormant. After four decades, the mountain is being watched again with focused intensity.