Scientists expected fluctuations, not a collapse this widespread.

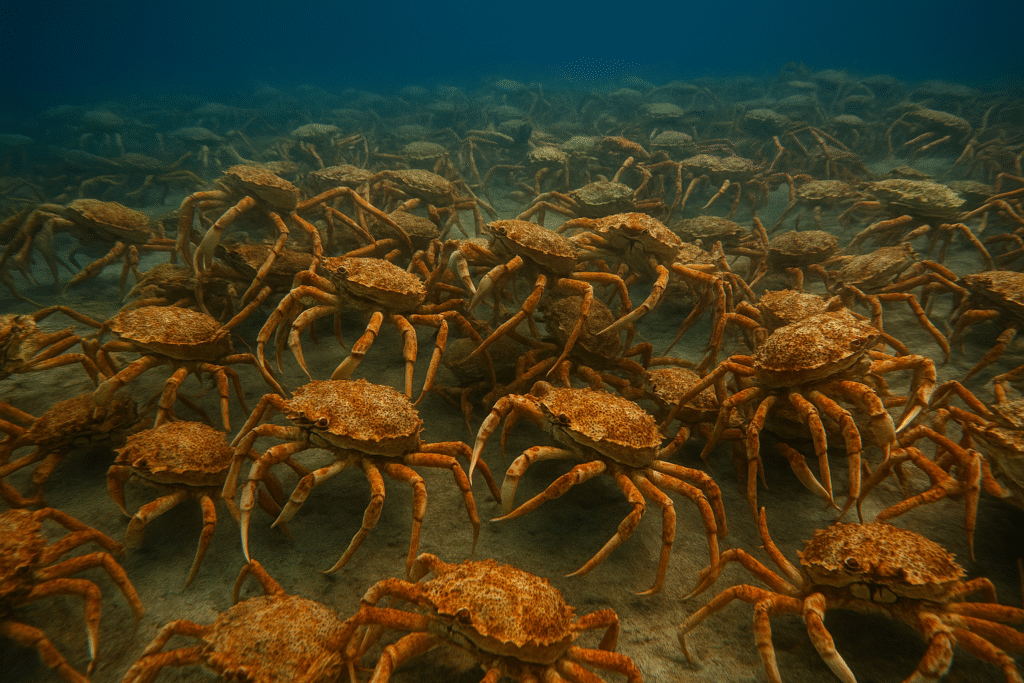

For decades, snow crabs were treated as a reliable constant in cold ocean ecosystems, their numbers rising and falling but never vanishing outright. Then surveys began coming back wrong. Entire regions reported sudden absences where dense populations once existed. The losses were not isolated to one fishery or one coastline, but stretched across multiple oceans at nearly the same time. As researchers compared data, a troubling pattern emerged. Something fundamental had shifted in the environment, and the disappearance was moving faster than the science meant to explain it.

1. Rising ocean temperatures pushed them past survival limits.

Snow crabs thrive only within a narrow temperature range, relying on cold waters to regulate their metabolism and oxygen needs. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Bering Sea warmed faster than any other ocean region between 2018 and 2022. That temperature spike forced crabs to burn more energy than they could replace, triggering mass starvation. As the sea lost its icy protection, the crabs’ habitat shrank dramatically, leaving millions unable to adapt or migrate quickly enough to cooler depths.

2. Starvation became the silent killer beneath the ice.

Warmer water doesn’t just heat bodies, it accelerates metabolism. The snow crabs’ bodies began requiring more calories at the exact moment their food supply, cold-dwelling algae and small crustaceans, started collapsing. Researchers later found entire swaths of the Bering Sea floor empty of life, as discovered by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Crabs that once thrived in abundance faced a slow-motion famine. The few survivors were thinner, smaller, and less fertile, signaling a long-term population decline that may take decades to reverse.

3. Disease outbreaks compounded the population crash.

When sea temperatures rise, pathogens spread more easily through weakened hosts. As reported by the National Science Foundation, bacterial and parasitic infections surged during the same years that crab numbers plummeted. Many infected crabs showed lesions and soft shells—symptoms linked to immune suppression from stress and malnutrition. Once disease began spreading through dense crab clusters, entire generations were lost at once. The ecosystem, already destabilized by heat and scarcity, couldn’t buffer against one more biological blow.

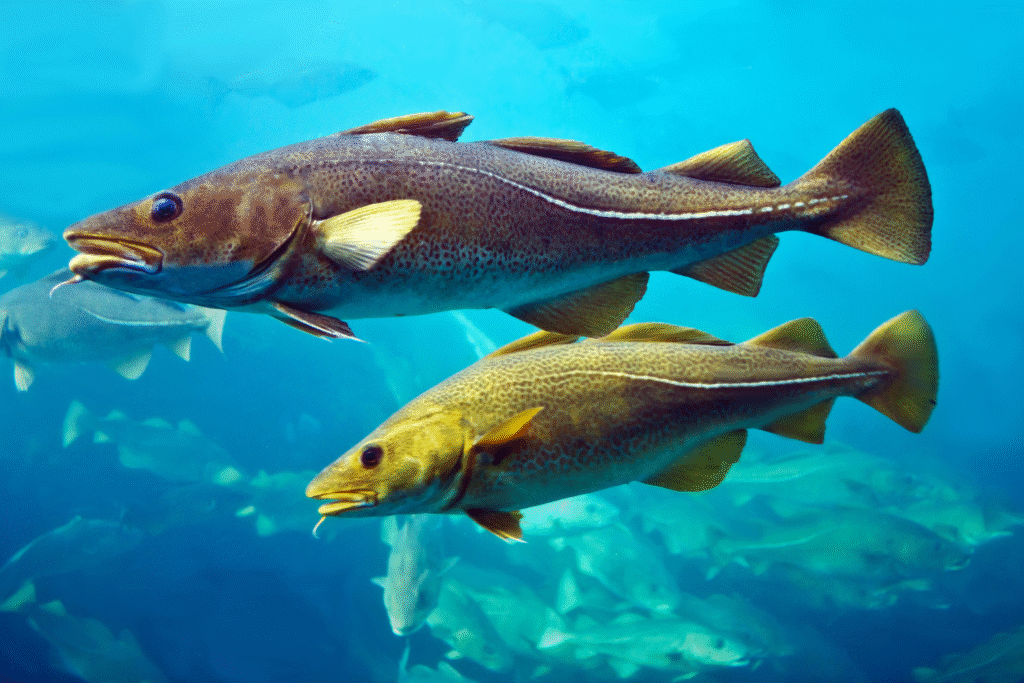

4. Competition for food intensified with predator expansion.

As Arctic waters warmed, species like Pacific cod and pollock migrated north, invading territory once dominated by snow crabs. These new arrivals devoured much of the benthic life that crabs depend on. The overlapping diets created a competition imbalance that snow crabs were evolutionarily unprepared for. In an ecosystem where temperature defines survival, even slight overlaps in habitat became battles for existence. With faster, more adaptive fish taking over, crabs were quietly edged out of their own food chain.

5. Sea ice loss stripped away their natural protection.

Young snow crabs depend on ice-covered waters to shield them from predators and stabilize temperature swings. The loss of seasonal ice in the Bering and Chukchi Seas exposed larvae to direct predation and unpredictable ocean conditions. Without that icy nursery, recruitment rates plunged, meaning fewer young crabs reached adulthood. Ice doesn’t just shape the landscape; it acts as the foundation for the entire Arctic food web. When it melts, everything built upon it begins to unravel, starting with the smallest and most fragile lives.

6. Overfishing worsened the decline already in motion.

Even before the sudden population crash, heavy harvesting pressure kept snow crab numbers near the edge of sustainability. When warming accelerated their mortality, fisheries were still operating based on outdated population models. The result was catastrophic. By the time the scale of the collapse became clear, more than 10 billion crabs were missing, forcing Alaska to cancel its 2022 and 2023 snow crab seasons. The fishing ban, though necessary, arrived as both a warning and a reckoning for Arctic management systems.

7. Shifts in ocean currents changed nutrient flows.

Melting ice and altered wind patterns disrupted the cold-water upwellings that feed Arctic plankton blooms. Those blooms are the first step in the snow crab food chain. When nutrient cycling faltered, the ripple effect reached everything from tiny amphipods to whales. In the absence of stable currents, energy moved unevenly through the system, starving some regions while overfeeding others. This imbalance created biological deserts where crabs once thrived—a haunting reflection of how fragile the ocean’s circulation really is.

8. The Barents Sea is now showing similar warning signs.

Across the Atlantic Arctic, snow crab populations in the Barents Sea are following the same pattern that struck Alaska. Warmer summers and declining sea ice have begun altering migration routes and reproduction timing. Scientists monitoring Norway’s waters warn that without colder refuges, the Barents population could crash next. The unfolding similarities across three oceans suggest a planetary-scale pattern, one that links Arctic ecosystems through a single thread, temperature rising just a few degrees too high.

9. Indigenous and coastal communities felt the loss immediately.

For many Alaskan and Russian coastal communities, snow crab harvests were a source of livelihood and food security. When the population vanished, boats sat idle, processing plants closed, and families lost generations of work overnight. Beyond economics, the collapse shattered cultural traditions centered on Arctic fishing seasons. The disappearance of crabs was more than biological; it was personal. What began as a marine mystery became a socioeconomic crisis stretching from the Bering Strait to the Arctic Circle.

10. Recovery will take decades, if it happens at all.

Snow crab populations reproduce slowly, and with their cold-water habitats shrinking, a full rebound remains uncertain. Some models predict partial recovery by mid-century, but only if warming trends reverse and strict protections stay in place. Others fear the species may never return to historical levels. Scientists are racing to understand how these losses fit into broader oceanic shifts. What’s becoming clear is that this isn’t a localized tragedy, it’s a warning from the seafloor about the pace of global change itself.