A subtle change carries enormous future weight.

For the first time in decades, researchers tracking Earth’s long term orbital cycles say the planet has entered a measurable shift. It is small enough that nobody feels it directly, yet meaningful enough that it changes how sunlight reaches different parts of the globe over extremely long timescales. These cycles have triggered ice ages before, and early signals suggest the next one has begun its slow approach. Nothing immediate is unfolding, but the groundwork is being laid in real time, far beneath the pace of daily weather.

1. Orbital records show Earth’s tilt is changing again.

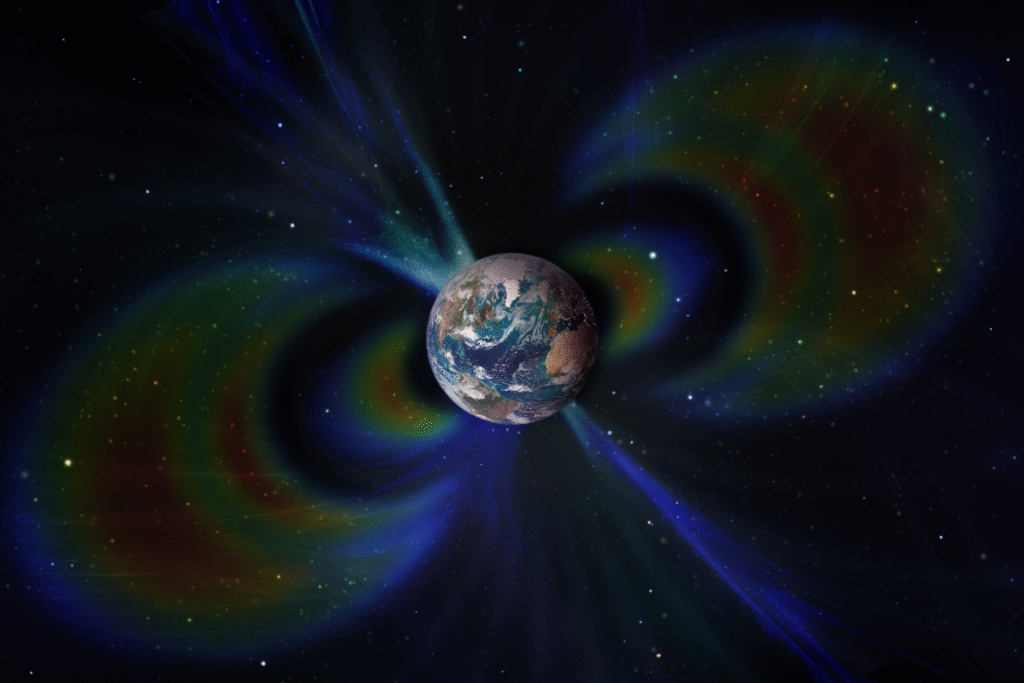

Scientists monitoring long term axial tilt detected subtle adjustments that match early stages of past glacial cycles, as reported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration at the end of their analysis on orbital variations. The tilt determines how much sunlight each hemisphere receives across the seasons, and when it shifts, global energy distribution moves with it. Even slight deviations can reshape climate behavior when sustained over thousands of years.

As the tilt continues adjusting, the planet enters a phase where summers gradually receive less solar energy. Cooler summers mean winter snow survives longer, slowly accumulating over generations. These changes act quietly but relentlessly, creating conditions that can eventually support widespread ice growth. Researchers stress that this process begins long before ice sheets actually expand.

2. Current cycles match early phases of past glacial periods.

When researchers compared today’s orbital pattern to ancient climate records, a familiar sequence appeared. Similar alignments occurred before previous ice ages, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and its assessments of long term Earth cycles. The pacing of the shift falls squarely within known Milankovitch timing, the mechanism responsible for triggering earlier global cool downs.

Matching this historical pattern does not mean rapid change. Instead, it signals the earliest stage of a slow cascade. Earth’s orbit subtly alters how sunlight is distributed, with northern summers gradually cooling more than southern summers. Over thousands of years, the imbalance favors the growth of long lived snow cover, allowing glacial regions to widen.

3. Temperature reconstructions suggest cooling will build gradually.

When paleoclimate specialists reconstructed conditions from previous orbital phases, they found a consistent cooling trend that deepened over millennia, as stated by the European Space Agency’s climate archives. Those long slopes of declining temperature produced the foundations for massive ice sheets. The present day shift mirrors the beginning of that same slope, although modern human driven warming temporarily masks the earliest signals.

The long term influence remains steady beneath surface trends. As orbital geometry continues drifting, the amount of summer sunlight in critical latitudes will eventually drop enough to favor persistent ice. Scientists describe the process as a slow tightening rather than an abrupt pivot, with momentum increasing across thousands of seasonal cycles.

4. Loss of summer heat sets the stage for snow persistence.

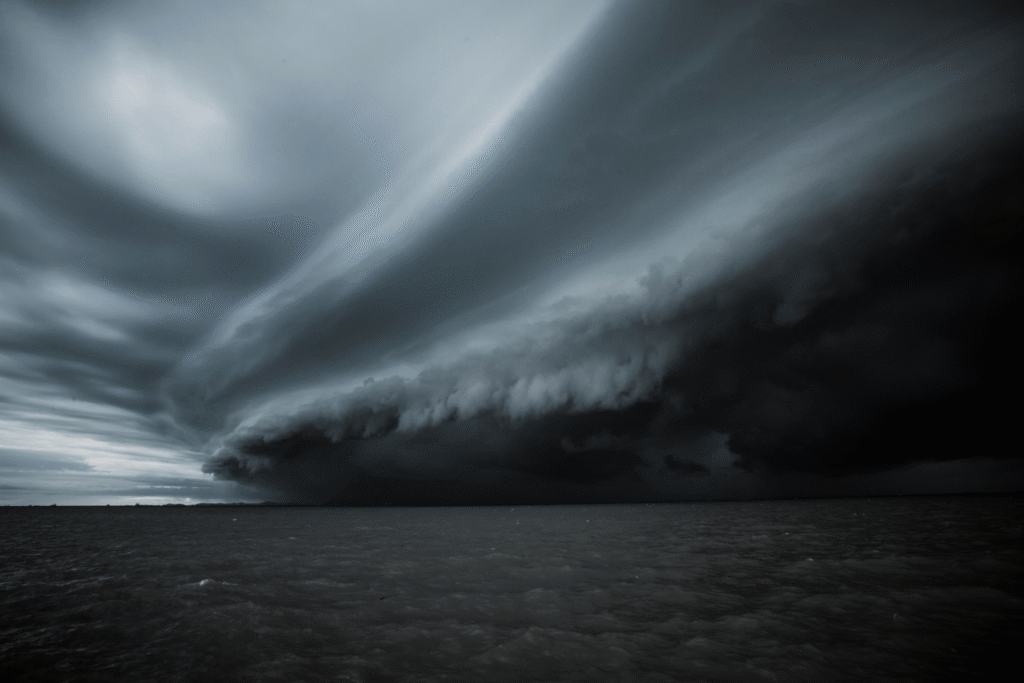

Each year of slightly reduced summer warmth allows winter snow to survive a little longer. At first it melts back only slightly less than usual. Over time, the loss compounds, preserving deeper layers from one year to the next. These small gains begin shaping the landscape in ways that are hard to reverse.

Once snow lingers, it reflects more sunlight, enhancing local cooling. That feedback strengthens the trend and prepares the ground for deeper regional changes. Although imperceptible in real time, the cumulative effect gradually pushes regional climates toward states that support permanent ice.

5. Northern land areas react most strongly to orbital shifts.

Large northern continents respond dramatically to reduced sunlight because they warm and cool faster than oceans. Their wide landmasses provide extensive space for snow accumulation, making them especially sensitive during early glacial phases. This reaction was seen during every major ice age in the geological record.

As orbital patterns continue shifting, regions at mid to high northern latitudes will show the earliest signs of long term cooling. The pattern does not unfold evenly, but it does follow a predictable arrangement shaped by geography. These zones become the anchor points where ice has historically begun its expansion.

6. Ocean circulation eventually adjusts to the new energy balance.

Long before large ice sheets appear, the oceans begin to react. Cooler northern summers gradually weaken patterns of heat exchange between hemispheres. Over extended timescales, this shift modifies currents that normally transport warm water northward. When these flows change, the surrounding atmosphere cools further.

This is one of the feedback mechanisms that reinforces early glacial development. Slower transfer of heat allows cold water to spread more widely, amplifying regional cooling. Over thousands of years, these changes help carve out the stable conditions that allow ice coverage to expand.

7. Ice sheets emerge only after long spans of slow buildup.

Contrary to dramatic depictions, ice ages do not begin with sudden ice formation. They grow through countless seasons of incremental gain. Snowfall accumulates layer after layer until its weight compresses it into ice. Once this process begins in earnest, glaciers extend outward from previously stable cores.

These early growth zones become seeds for the larger ice sheets that define full glacial periods. What begins as slight summer cooling eventually transforms into massive landscapes shaped by stable ice. This is the same trajectory past ice ages followed during earlier orbital shifts.

8. Global sea levels respond once glaciers begin their advance.

As more water becomes locked in ice, sea levels slowly drop. The change is gradual in the early stages but accelerates once ice sheets gain enough mass. Historical records show sea level declines that stretched across thousands of years, reshaping coastlines and altering global climate further.

Reduced sea levels also modify the exposure of land bridges and continental shelves, influencing ecosystems and migration patterns. These conditions are far in the future, but they reflect a predictable response once glacial buildup intensifies. The orbital shift sets this chain in motion long before visible ice appears.

9. The process unfolds beneath present climate conditions.

Human driven warming temporarily masks the subtle influence of the orbital shift, complicating how the early stages appear at the surface. The long term signal, however, continues regardless of contemporary trends. Orbital cycles operate on timescales far beyond the reach of short term climate forces.

Scientists often describe the system as two separate tracks running concurrently. One influences decades and centuries, while the other shapes tens of thousands of years. The orbital signal is slow but persistent, and over geological time it consistently wins out once the cycle matures.

10. The next ice age begins with barely visible steps.

The earliest phases of a glacial cycle rarely look dramatic. They begin quietly with slight summer cooling and small accumulations of snow. Over extended periods, these imperceptible changes gain strength, gradually forming the backbone of an ice age. Today’s orbital configuration sits at the start of that long trajectory.

The process will unfold slowly, far beyond any human timeframe, yet the foundations are already shifting. Earth is entering the opening chapter of another long cycle, one that past epochs have written many times before. The orbital drift is underway, and its consequences will unfold across the distant future.