The heat is moving, not disappearing.

The idea that oceans are cooling the planet feels reassuring during an era of relentless climate headlines. Water absorbs heat, spreads it out, and hides it from everyday experience. That can look like relief if you only watch surface air temperatures. Scientists have been measuring the oceans carefully for decades, across depths and basins. Those records show a system storing energy, not undoing warming. What happens below the waves shapes storms, sea level, ecosystems, and climate stability far beyond the shoreline.

1. Ocean heat content keeps rising year after year.

Ocean heat content measures how much energy is stored through the water column, not just at the surface. Since systematic tracking began in the mid twentieth century, every decade has added more heat than the one before. This trend appears in the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, and Southern oceans alike.

The increases are not subtle. Recent years have shattered previous records, indicating sustained accumulation rather than variability. This pattern shows that heat is being transferred into the ocean faster than it can be released, according to data compiled by NASA. A cooling ocean would show plateaus or declines, which the measurements do not.

2. Surface temperature dips hide deeper warming trends.

Short lived drops in sea surface temperature often fuel claims that oceans are cooling. Those claims overlook how heat moves vertically. Winds and currents mix warm water downward, spreading energy into deeper layers that satellites cannot detect.

Instrument data from buoys and autonomous floats show continued warming below the surface even during surface slowdowns. This has been documented across multiple basins, especially in the Southern Ocean. The apparent contradiction disappears once depth is considered, as reported by NOAA. What looks like cooling is usually redistribution, not loss of heat.

3. Heat absorption delays warming rather than stopping it.

Oceans absorb most of the excess heat caused by greenhouse gases. That buffering slows atmospheric warming temporarily, which can feel like mitigation. But the energy remains within the climate system, stored and ready to influence future conditions.

Stored heat resurfaces through currents, seasonal cycles, and large climate patterns. It contributes to sea level rise through thermal expansion and fuels extreme events later on. Climate assessments emphasize this delayed effect rather than permanent relief, a conclusion reinforced in assessments by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Absorption changes timing, not outcomes.

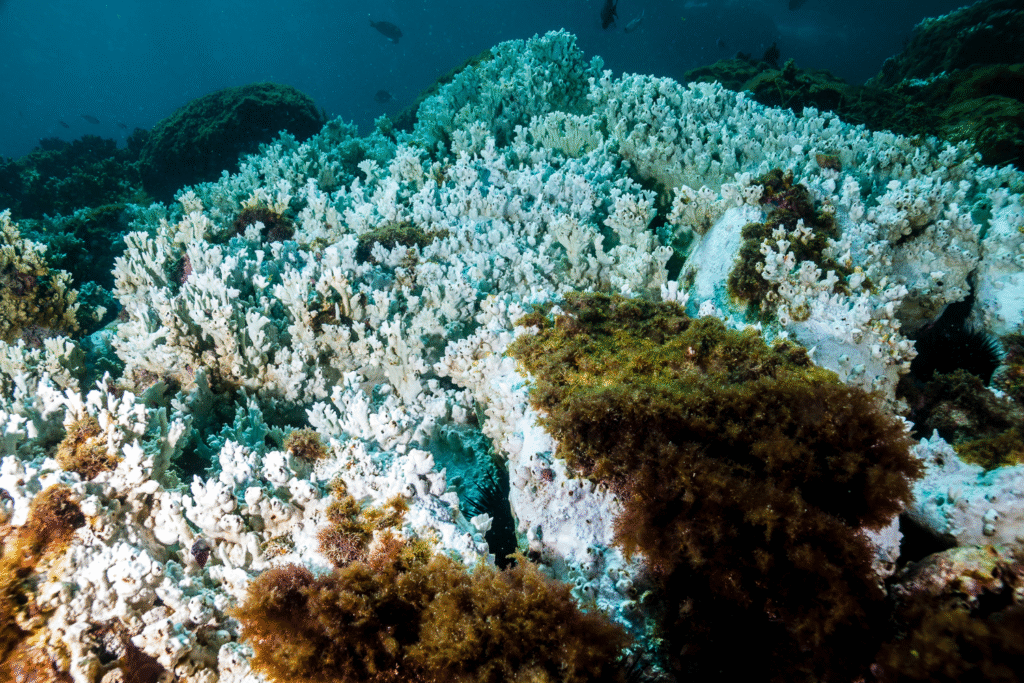

4. Marine heatwaves reveal the rising baseline clearly.

Marine heatwaves are prolonged periods of unusually warm ocean temperatures. Over recent decades, they have become more frequent, longer lasting, and more intense. Regions like the northeast Pacific and Mediterranean now experience events that persist for months.

These extremes reflect a higher baseline temperature, not isolated anomalies. As average conditions warm, thresholds for heatwaves are crossed more easily. The impacts ripple through ecosystems, damaging kelp forests, coral reefs, and fisheries. A cooling ocean would reduce these events. The observed escalation shows that underlying heat content continues to climb.

5. Deep ocean warming locks in centuries of change.

Heat is now penetrating below two thousand meters, especially around Antarctica where dense water sinks. Once energy reaches these depths, it remains trapped for centuries due to slow circulation.

This deep storage commits the planet to long term consequences regardless of near term emission changes. Sea levels will continue rising from thermal expansion alone, and circulation patterns will stay altered. Cooling claims rarely account for this timescale. The deep ocean acts as a long memory, preserving heat far beyond human planning horizons.

6. Ice loss accelerates as oceans warm underneath.

Glaciers and ice sheets interact directly with ocean water. Warmer currents erode ice shelves from below, thinning them and reducing their ability to restrain inland ice flow.

This process has been observed around Greenland and Antarctica, where melt rates correspond closely with ocean temperature changes. Air temperature alone cannot explain the pace of loss. A cooling ocean would slow basal melting. Instead, warming water increases ice vulnerability, contributing to faster sea level rise and reshaping polar stability.

7. Ocean circulation changes signal energy imbalance.

Ocean currents depend on temperature and salinity differences. As heat accumulates unevenly, these gradients shift, altering circulation patterns. Evidence suggests weakening in major systems like the Atlantic overturning circulation.

Such changes redistribute heat and moisture globally, influencing rainfall and seasonal temperatures. Regions may cool temporarily while others warm sharply, creating misleading signals. These circulation adjustments reflect imbalance, not recovery. A cooling system would trend toward stability, whereas current observations show increasing variability tied to excess stored energy.

8. Acidification follows the same uptake pathways.

The ocean absorbs carbon dioxide alongside heat. As CO2 dissolves, seawater becomes more acidic, altering chemistry worldwide. This trend closely tracks regions of strong heat uptake.

Acidification stresses shell forming organisms and coral reefs, reducing growth and survival. Combined with warming, it lowers ecosystem resilience. These chemical changes confirm continued absorption rather than cooling. A truly cooling ocean would show slowing CO2 uptake. Instead, chemistry records reinforce the physical evidence of an ocean under increasing load.

9. Storm behavior reflects warmer ocean conditions.

Tropical cyclones and atmospheric rivers draw energy from warm ocean surfaces. Higher water temperatures increase moisture availability and storm intensity. This relationship is well established in observational records.

Recent decades have seen more rapid storm intensification and heavier rainfall events. These patterns align with warmer oceans providing additional fuel. Cooling claims conflict with these outcomes. The storms themselves act as messengers, translating stored ocean heat into visible atmospheric extremes.

10. Freshwater inputs are reshaping ocean density.

Melting glaciers and increased rainfall add large volumes of freshwater to the ocean, particularly in polar and subpolar regions. This freshening changes water density, affecting mixing and current formation.

Lower density surface layers can trap heat below, slowing its release to the atmosphere. This mechanism allows warming to persist even when surface conditions fluctuate. Freshwater driven stratification is a newer concern, emerging clearly in recent decades. It represents another way oceans store heat more efficiently, complicating any narrative of planetary cooling.