A grave discovery unsettles long accepted hierarchies.

High in Peru’s northern highlands, archaeologists uncovered a burial that immediately stood out. The grave, referred to as WMP 6, was carefully constructed, richly furnished, and positioned in a way reserved for individuals of authority. Nothing about it suggested modesty or marginal status. Then biological analysis revealed the individual was female. That single confirmation forced researchers to confront an uncomfortable possibility. Ancient power structures may have been far more complex than the records modern scholars built around them, shaped as much by assumption as by evidence.

1. The burial contained unmistakable symbols of political authority.

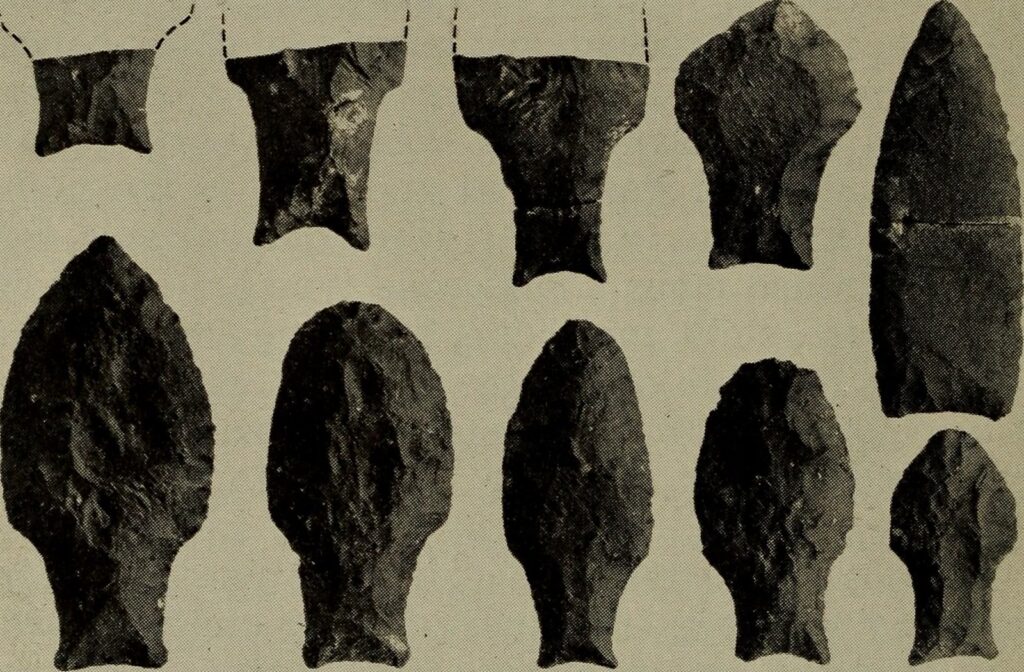

The grave WMP 6 at Wilamaya Patjxa, a high altitude site in Peru’s Puno region near Lake Titicaca, included finely crafted stone tools, hunting weapons, and ceremonial objects long associated with elite authority in early Andean societies. These items were carefully positioned, following patterns seen in other high status burials from the southern highlands rather than casual or domestic interments.

The consistency of the layout left little room for reinterpretation. The objects signaled recognized leadership within the community, not symbolic tribute or status inflation. According to National Geographic, the grave goods closely matched those attributed to individuals with political or ritual authority, forcing a reevaluation of who was historically assumed to hold power.

2. Skeletal analysis confirmed the individual was biologically female.

Initial hesitation followed the excavation at Wilamaya Patjxa, reflecting how deeply gender expectations shaped interpretation. Detailed skeletal analysis focused on pelvic morphology, cranial traits, and dental structure, all standard indicators used in biological sex identification. Independent examinations reached the same conclusion across multiple assessments. The skeleton belonged to a female, a huntress, who was then posthumously granted the name “Warawara”, meaning “star” by the Aymara community.

Once confirmed, the finding dismantled alternative explanations that framed the burial as symbolic or anomalous. The evidence left little ambiguity. As reported by Science, the research team acknowledged that elite burials had often been classified as male by default, revealing how long standing assumptions guided interpretation more than anatomical data.

3. The burial dates to an era labeled male dominated.

Radiocarbon analysis placed the burial at more than nine thousand years old, during a period often described as dominated by male hunters and leaders. That framework shaped decades of archaeological interpretation across the Americas, reinforcing rigid assumptions about early social roles.

The Peruvian burial contradicts that narrative directly. It suggests women held authority far earlier than previously recognized. As stated by Smithsonian Magazine, the discovery indicates that leadership in early Andean societies was not restricted by gender in the way modern models have assumed, requiring a reassessment of long standing historical timelines.

4. Archaeological bias shaped conclusions long before excavation.

For generations, archaeologists often assigned gender based on grave goods rather than skeletal evidence. Weapons implied male identity, while tools associated with food or textiles implied female roles. These shortcuts became embedded practices rather than questioned habits.

This burial exposes the cost of that approach. Evidence that conflicted with expectations was often reinterpreted or minimized. The find forces researchers to reconsider how many elite female burials were misclassified, not because data was lacking, but because assumptions quietly guided interpretation from the start.

5. Power in early societies may not have followed rigid lines.

The burial suggests authority may have been distributed through skill, lineage, or ritual knowledge rather than biological sex. Leadership could have shifted depending on circumstance, environment, or social need, leaving fewer rigid markers in the archaeological record.

Such flexibility helps explain why earlier evidence was overlooked. If power roles were fluid, they would resist simple classification. The discovery encourages broader thinking about how influence operated in early human communities without relying on fixed hierarchies imposed by later cultural expectations.

6. Weapons alone no longer define leadership roles.

The presence of hunting weapons in the grave was once considered definitive proof of male status. This assumption shaped interpretations across countless sites. The Peruvian burial directly challenges that logic.

Weapons may have symbolized authority, protection, or ritual responsibility rather than gender. Separating tools from identity allows archaeologists to revisit other burials with fresh perspective. Leadership expression may have been tied to responsibility rather than sex, a distinction long blurred by modern bias.

7. Textiles and ritual objects carried political meaning.

The burial included finely produced textiles and symbolic items that required advanced skill and time to create. These objects were not everyday possessions. They signaled access to labor networks and cultural authority within the community.

In Andean societies, textiles often communicated rank, lineage, and power. Their inclusion reinforces the interpretation of recognized leadership. This detail strengthens the argument that political authority extended beyond physical strength into ceremonial and cultural influence held by women as well as men.

8. Historical narratives favored simplicity over reality.

Over time, archaeological storytelling favored clean categories and linear hierarchies. These narratives were easier to teach and replicate, even when evidence hinted at greater complexity. Nuance was often sacrificed for clarity.

The burial disrupts that approach. It reveals societies that were adaptive and layered rather than rigid. When discoveries challenge long accepted frameworks, they expose how much was trimmed away in the pursuit of simple explanations that never fully matched reality.

9. Ancient power was misread more than misrecorded.

This burial does not represent an isolated exception. It highlights a pattern of interpretation shaped by modern expectations rather than ancient realities. Gender assumptions influenced how evidence was sorted, labeled, and explained.

The error was not made by ancient societies. It emerged later, during analysis. By confronting that mistake, archaeologists can begin reassessing other sites with greater care. The discovery reframes ancient power as something broader, more inclusive, and long misunderstood rather than absent or rare.