This animal is so genetically confused, early scientists thought it was a hoax.

The platypus is what happens when nature decides to remix every taxonomic category at once. It has bird parts, reptile leftovers, mammal basics, and then some details that feel like a practical joke. Even today, scientists still lowkey argue about how to classify it. This thing lays eggs but makes milk, swims like a duck but has venom like a snake. If it sounds made up, that’s because it kind of is.

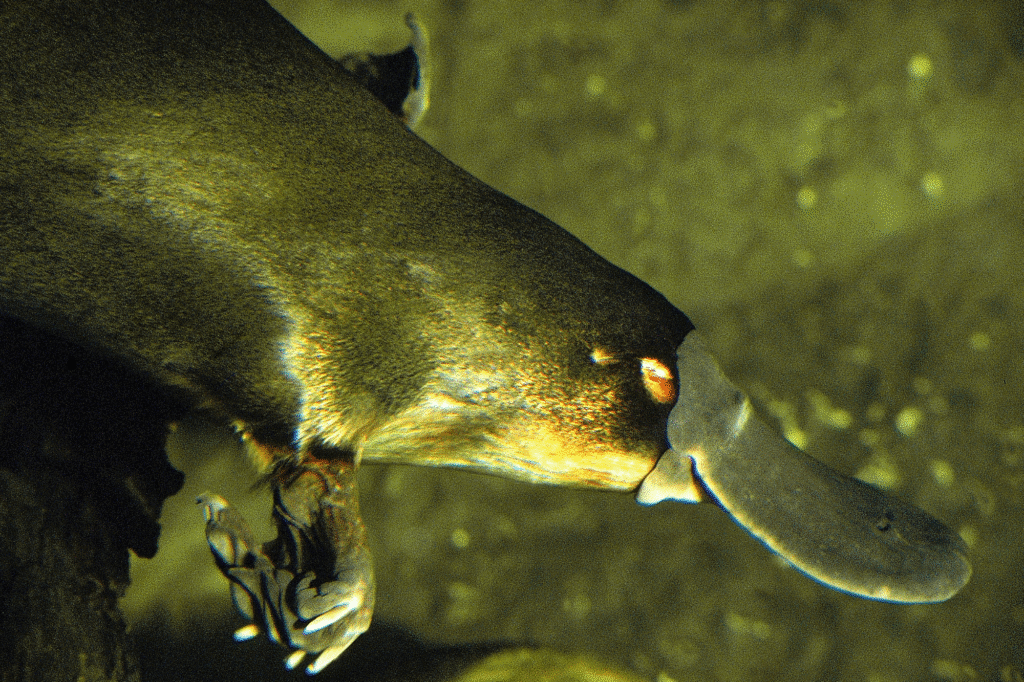

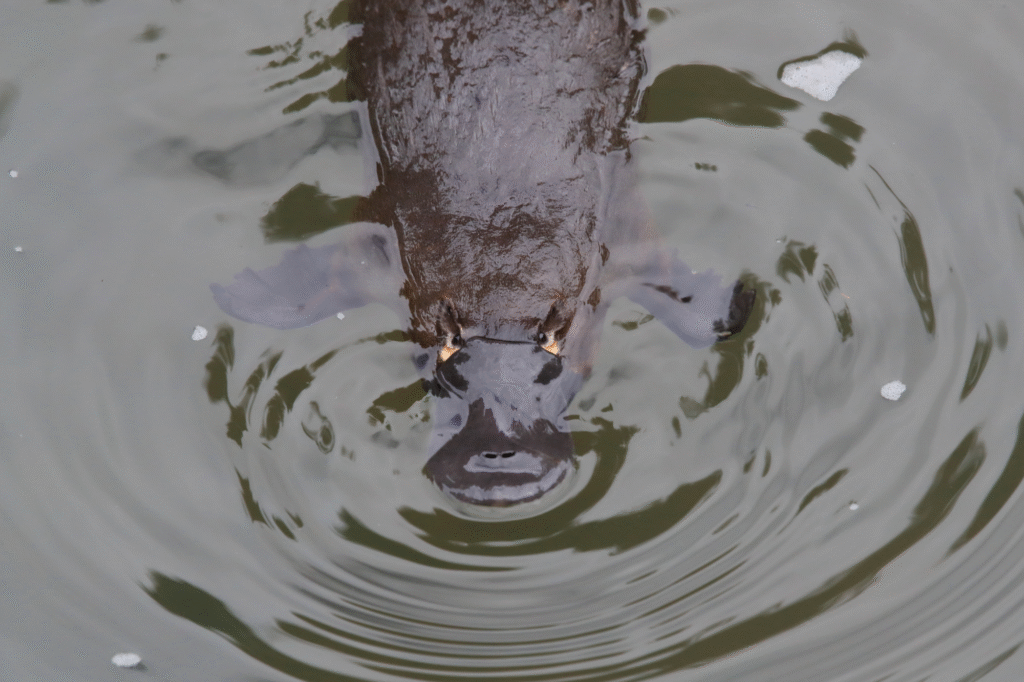

1. That duckbill does way more than sniff out snacks.

At first glance, it’s giving duck cosplay. But the platypus’s bill is its most elite piece of gear, according to the experts at the National Geographic. That soft, flat surface is packed with electroreceptors, letting it detect electric fields from muscle contractions of prey underwater. No other mammal has this. Not even close.

It can literally hunt with its eyes, ears, and nose closed. The moment a shrimp twitches, the platypus senses the electric pulse like a sixth sense. It doesn’t need to see. It doesn’t even need to try that hard. Its bill reads the water like radar, making murky rivers feel like glass.

This ability is usually found in fish and sharks, not fuzzy egg-layers chilling in Australian streams. It’s one of those biological hacks that feels too sci-fi to be real but is fully standard issue for the platypus.

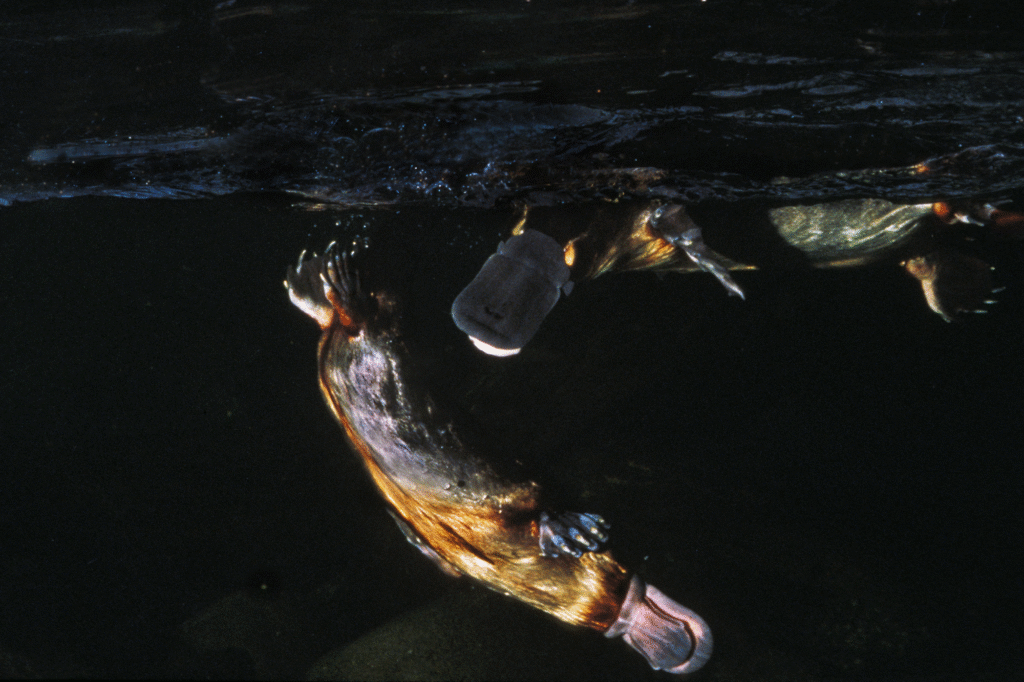

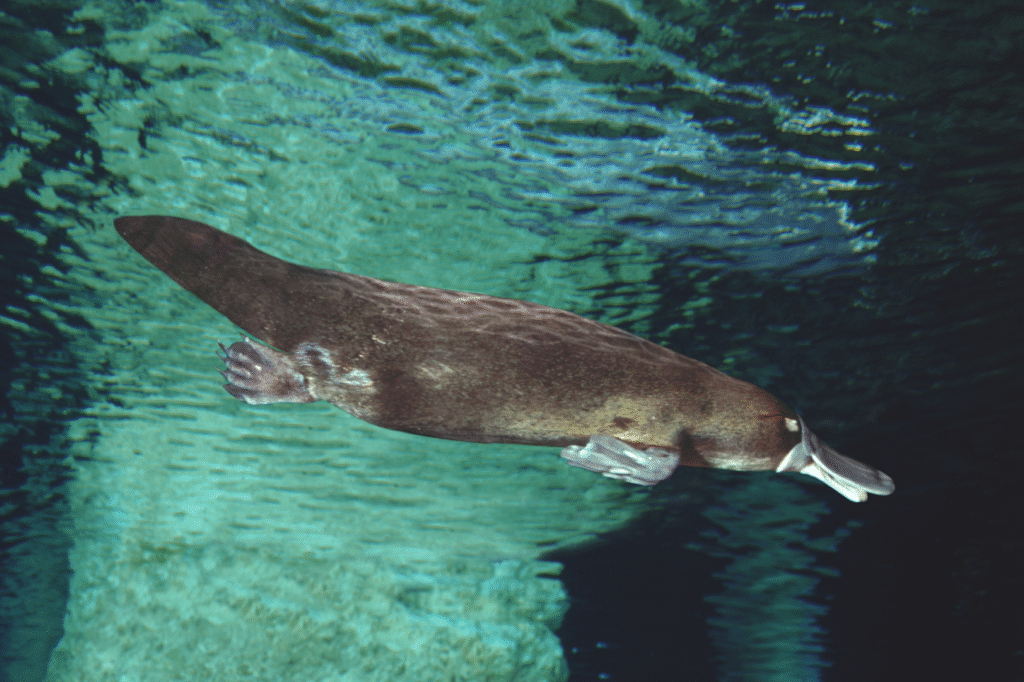

2. Webbed feet mean it swims like an otter but walks like it forgot how.

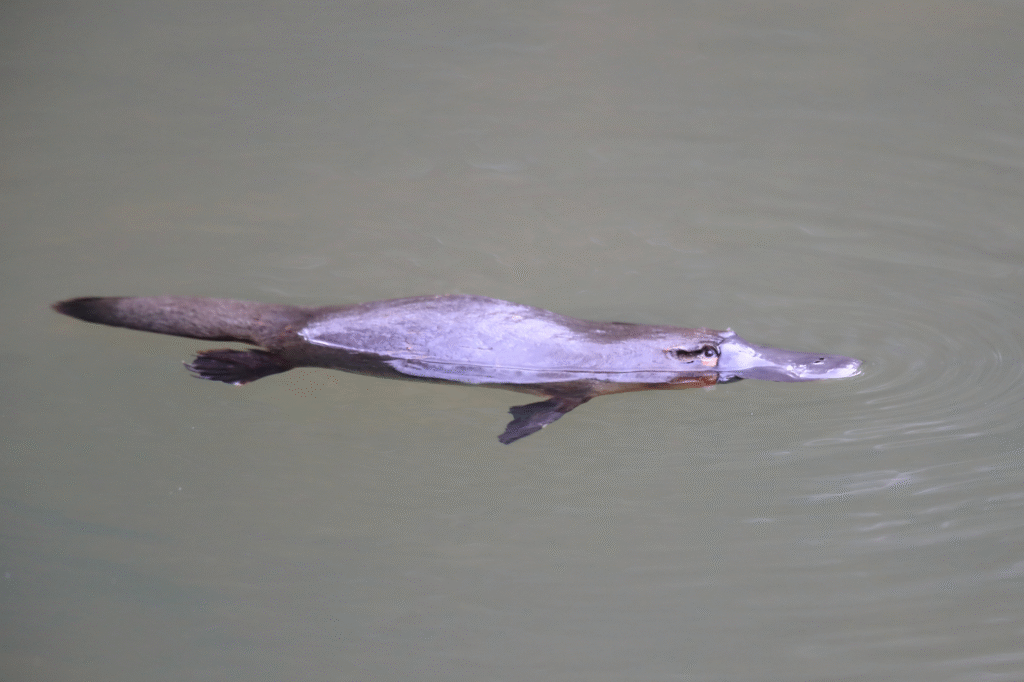

Platypuses are aquatic first and awkward land creatures second, as reported by Ariel Berkoff at the World Wildlife Fund. Their front feet have full webbing that extends beyond their claws, like they’re built for Olympic backstroke. These webbed paws fold back when they walk so the claws can touch ground, but in water, they function like tiny flippers. Zero drag, high control.

On land, though, it’s another story. The webbing makes their gait clumsy and wide. Their limbs kind of splay out, forcing them to shuffle around like they missed the land mammal memo. But in water, they’re sleek. They use their tail and hind feet for steering, front feet for propulsion, and can stay submerged for minutes without stress.

The dual function is weirdly specific and perfectly evolved for their amphibious lifestyle. Still, it makes them look like two completely different animals depending on where you catch them.

3. That fur is more beaver than mammal, and way more efficient.

It’s not fluffy for fun. Platypus fur is ultra dense, with over 800 hairs per square millimeter, as stated by Hannah Keyser at Mental Floss. That’s more than a polar bear. More than a cat. More than you’d ever guess looking at its little soggy body. This fur keeps it dry even after hours underwater. Water never hits the skin.

There’s an outer layer that repels water and a super soft undercoat that traps air and body heat. That combo keeps them warm in freezing streams without needing thick fat layers like seals or whales. It’s subtle, but it’s kind of the techwear of fur evolution.

This whole system works better than most wetsuits and does it without sacrificing mobility. It’s not for show. It’s a thermal barrier that lets them keep doing platypus things at all hours, in any season, without ever catching a chill.

4. Platypus moms feed their babies without needing any standard equipment.

Female platypuses don’t have the usual setup for delivering milk, according to the authorities at the Australian Museum. Instead, they release it straight through their skin from special patches on their belly. The milk gathers in shallow grooves between the fur, and the babies just slurp it up directly like soup off a sponge. It’s strange, but surprisingly effective.

This is one of those monotreme moves that makes you question everything you thought you knew about mammals. There are no teats, no complicated structures—just skin and instinct. The babies, born tiny and blind, are completely dependent on this system as they grow inside a safe, cozy burrow.

It feels like something ancient, but not in a failed-experiment kind of way. More like an alternate route that evolution explored and somehow made work. The system might look unusual, but it does exactly what it needs to without wasting energy on unnecessary parts. Total efficiency with maximum weirdness.

5. Males are venomous and the delivery system is straight up savage.

Only the males have it, and they only use it during mating season. On their hind legs, there’s a spur—kind of like a little fang—that can inject venom strong enough to paralyze a dog. The pain in humans isn’t fatal, but it lasts for weeks and doesn’t respond to most painkillers.

This venom isn’t just defensive. It’s likely a way to fight off other males and assert dominance when everyone’s competing to mate. It contains over a dozen unique compounds not found in any other animal, and scientists still haven’t cracked them all.

Most mammals don’t come with venom at all. The platypus just casually carries around toxic spurs like it’s normal. Evolution didn’t just throw in a curveball here. It launched it from the bleachers.

6. They skip the stomach completely and still digest food just fine.

This is one of those facts that sounds fake but is very much real. Platypuses don’t have a true stomach. Food moves from their throat directly into the intestines, bypassing the whole acid bath situation most animals rely on.

Instead of hydrochloric acid breaking down meals, enzymes take over. Their food is soft enough that they don’t need to chemically destroy it first. Tiny shrimp, worms, insect larvae—it’s all digestible with minimal prep. This setup works because their diet is low in hard-to-digest stuff, so there’s no need for a gastric chamber.

By skipping the stomach entirely, they also lower the energy cost of digestion. It’s kind of genius in a minimalist way. They basically Marie Kondo’d their digestive system and only kept what sparked biological joy.

7. Their tail looks like it belongs to a beaver but it’s doing its own thing.

At first glance, you’d think a platypus tail was copied and pasted from a beaver. It’s flat, broad, and helps them steer through water like a rudder. But that’s not all it’s doing. It’s also a backup battery. Platypuses store fat in their tails, kind of like a camel stores energy in its hump.

During lean times, like when food gets scarce or water levels drop, they tap into this reserve. The tail shrinks down noticeably as they burn through the fat. It’s not aesthetic, it’s functional. The shape and size actually reflect their health, so you can lowkey monitor how a platypus is doing just by tail-checking.

This multi-use appendage does not assist in balance the way tails do for other mammals. Platypuses don’t climb trees or run around needing counterweight support. Their tail was never about that life. It’s water control and energy storage rolled into one low-key chunk of genius.

8. They share part of their skull anatomy with reptiles and echidnas.

Hidden under all that fur and oddness is a skull that’s more confusing than it has any right to be. The base of a platypus skull resembles both echidnas and certain reptiles, which doesn’t exactly help when you’re trying to pin down its family tree. It has features like sprawling jaw bones and cranial structures that scream “ancestral remix.”

What this suggests is that the platypus didn’t evolve from your average rodent or carnivore line. It came from a much older lineage that split off before mammals really committed to being mammals. They retained structural elements that most modern mammals lost millions of years ago.

You’re basically looking at a skeleton that straddles eras. Half ancient, half functional. It’s less like an upgrade and more like an old operating system that somehow still runs.

9. Testicles, but make them internal like a minimalist’s dream.

Male platypuses do not have external testicles. They keep them tucked up inside the body, where most mammals have long since decided things need to hang. This makes them more like birds and reptiles, not your usual furry land dwellers.

Why? Temperature regulation is the obvious question, but the platypus isn’t here to explain. Somehow, sperm development works just fine internally. No scrotum needed. They just skipped that whole external pouch trend and never looked back.

It’s one of the many anatomical details that throws mammalogists into an existential spiral. Everything we thought we knew about how mammals are built kind of unravels when you open up a platypus. They’re rewriting the basic blueprint in real time and still managing to reproduce just fine.

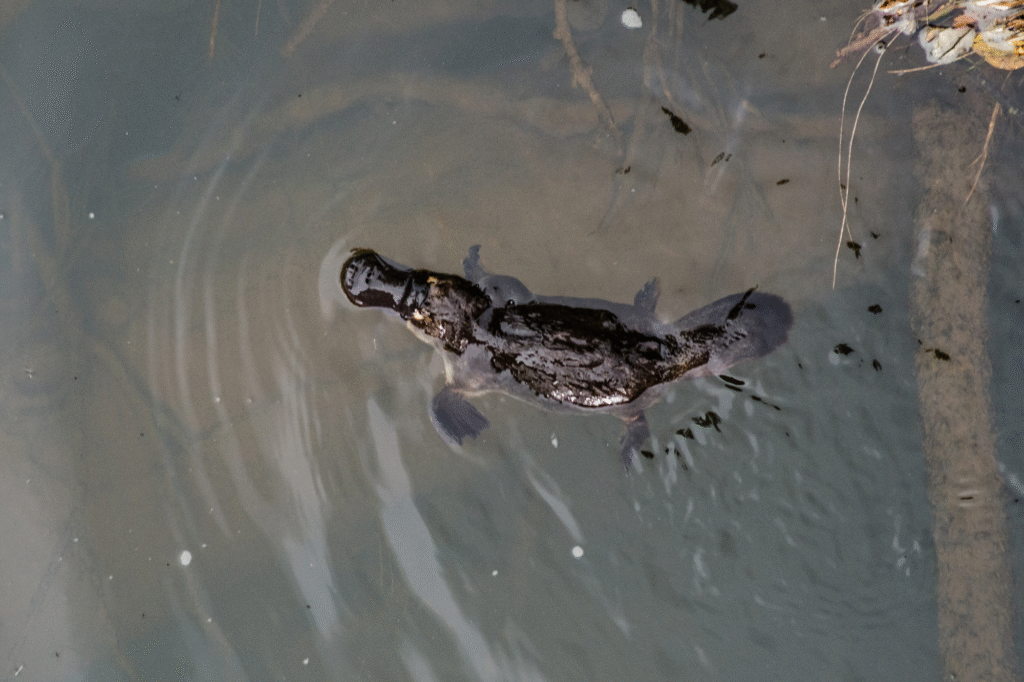

10. Their walk looks more like a lizard’s than a mammal’s.

Platypuses don’t walk with their legs under them like dogs or cats. Instead, their limbs splay out to the sides, and they move with a side-to-side shuffle that’s more reptile than mammal. It’s an energy-inefficient way to move, but it works for the short distances they cover on land.

This gait is a throwback. Most mammals evolved away from this posture because it wastes energy and limits speed. But since the platypus barely spends time on land, it never got the memo. Their body plan didn’t update because it didn’t have to. They only use this awkward crawl to get from the water to a burrow and back.

It’s kind of hilarious watching one move on grass. It looks like it’s wearing an invisible weighted blanket. But once it hits water, the weird walk doesn’t matter anymore. They’re instantly graceful and unbothered.

11. Instead of teeth, adults mash their food with keratin plates.

Baby platypuses are born with teeth, but they lose them before adulthood. Once they grow up, they rely on hard pads made of keratin to grind up their food. Keratin, by the way, is the same material your nails are made of. So basically, they chew with reinforced fingernail plates.

They scoop up insects and grit from riverbeds using their bills, then mash it all together between those pads like a food processor. It’s not elegant, but it gets the job done. They swallow whatever is soft enough, and the rest gets spit out.

No molars, no incisors, just press-and-crush vibes. It’s one more reason scientists didn’t even believe they were real when the first specimen was sent to Europe. They thought someone had stitched parts together from multiple animals. The dental situation did not help the case.

12. The cloaca throws off everything you thought you knew about mammals.

Birds have them. Reptiles have them. Amphibians have them. Most mammals do not. Platypuses absolutely do. A cloaca is a single opening that handles reproduction, urination, and defecation all in one spot. No separate plumbing system. Just one exit and entry point for everything.

This setup puts the platypus firmly in its own lane. Most mammals have a more specialized system with different openings for different functions. The platypus keeps it prehistoric. The cloaca is what gave the entire monotreme group its name—“one hole.”

It’s one of those traits that reminds you this animal never got around to choosing a side in the mammal vs. reptile argument. They just rolled with a system that still works and never bothered reinventing it.

13. Electroreception shows up twice, and yes, it’s that important.

We already covered the duckbill. But let’s circle back because the platypus doesn’t just have a few sensors. It has over 40,000 electroreceptors lining the bill. That level of sensory data lets it build a 3D map of its environment in total darkness, just by reading electrical fields.

It’s a flex so specific that only sharks and a few fish even come close. In mammals, it’s unheard of. And yet, here’s the platypus casually reading the voltage off a worm hiding under a rock while paddling around like it’s no big deal.

That sense alone gives it predator powers on par with animals way higher up the food chain. It makes up for mediocre vision and clumsy movement. The platypus thrives not in spite of being weird, but because of it.

14. Their fur is double-layered and smarter than it looks.

You can’t tell just by petting one (if you ever get the chance), but platypus fur is operating on two levels. There’s a super fine underlayer that traps air close to the skin, and a coarser outer layer that keeps water out. Together, they work like a dry suit.

This means the platypus stays warm and buoyant no matter how long it swims. The inner layer never gets wet, even when it’s doing underwater acrobatics. That’s a huge deal in chilly mountain streams where hypothermia could take out most land mammals in under an hour.

It’s one of the most effective insulative systems in the animal kingdom. And it’s subtle. You wouldn’t guess that from looking at their awkward little bodies, but nature really gave them a high-tech wetsuit.

15. The whole egg-laying situation is the final curveball.

Mammals don’t lay eggs. Except, apparently, when they do. Platypuses are one of only five known monotremes, which are the only mammals that lay eggs. The female lays soft-shelled eggs and then curls around them in a burrow, incubating them with her body heat like a weirdly fluffy bird.

After about ten days, the babies hatch—completely helpless—and nurse from milk patches on the mother’s skin. The process is way more reptilian than mammalian, but it works. And they’re thriving in their little corner of Australia, completely unbothered by the fact that the rest of the animal kingdom moved on from this whole egg thing.

It doesn’t feel like evolution missed a step. It feels like it went off-script on purpose. The platypus isn’t trying to fit in, and that’s exactly why it works.