Ancient ground scars challenge early technology timelines.

In the gypsum flats of what is now southern New Mexico, time briefly stopped working the way it usually does. Footprints hardened, drag marks settled, and layers sealed everything in place. When researchers uncovered these tracks, dated to roughly twenty two thousand years ago, they expected a story about migration. Instead, they found something quieter and stranger. The marks suggest not just people walking, but people moving weight across a difficult landscape with intention, planning, and tools.

1. Ancient footprints reveal repeated linear drag patterns.

The trackways at White Sands National Park show human footprints running alongside long, shallow grooves carved into soft ground. These grooves extend for meters at a time and appear consistently beside walking paths rather than randomly across the surface. Their depth changes with terrain, growing lighter on firmer ground and deeper where sediment softened. This variation suggests control rather than chance, pointing to an object deliberately pulled by human hands over distance.

Researchers studying these preserved surfaces concluded the grooves were created by dragged loads moving with people rather than natural forces, according to the U.S. National Park Service. Wind and water patterns do not create parallel tracks that align with human stride length and direction.

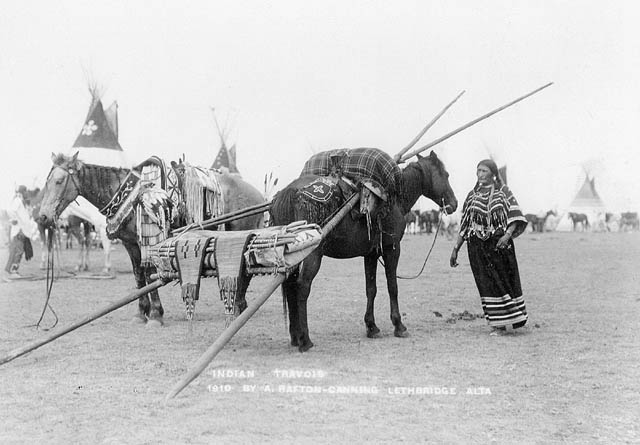

2. The marks closely resemble early sled like transport tools.

The shape and spacing of the drag marks closely match what archaeologists recognize as travois style movement. A travois uses two poles attached behind a person, allowing heavy items to slide along the ground. The grooves at White Sands show the same paired lines, tapering slightly and remaining steady across long distances. This pattern is difficult to replicate accidentally and appears repeatedly across multiple trackways.

Comparative experiments dragging wooden poles across soft sediment produce nearly identical impressions, matching the ancient marks in width and continuity, according to Science. These similarities suggest early humans understood that dragging reduced effort compared to carrying.

3. Adults and children moved together within the same paths.

One of the most revealing details is the presence of small child footprints alongside adult tracks within the same drag paths. These footprints are not scattered or crossing randomly. They move together in the same direction, maintaining consistent spacing. This implies group travel rather than isolated activity and suggests planning rather than urgency or escape.

Detailed footprint analysis shows different stride lengths and foot sizes traveling together while maintaining shared drag lines, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. This combination strongly suggests families moving supplies together, not individuals acting alone.

4. Ice Age terrain made carrying loads impractical.

During the Last Glacial Maximum, the White Sands region was a shifting mix of wet gypsum flats, shallow water, and unstable ground. Carrying heavy objects through such terrain would have been exhausting and inefficient. Each step would sink, slide, or stick, slowing movement and increasing risk. Transporting food, tools, or children required solutions that reduced physical strain.

Dragging objects along the surface spreads weight over distance rather than concentrating it on the body. The environment itself supports the idea that dragging tools were not optional innovations but necessary adaptations to survive regular travel.

5. Track alignment shows deliberate route selection.

The footprints and grooves do not wander randomly across the ancient surface. Instead, they follow relatively straight paths that avoid deeper mud zones and unstable patches. This suggests familiarity with the landscape and an understanding of where travel was safest and easiest. Such alignment points to repeated use rather than one time experimentation.

Route planning implies that these paths were known and reused. Transport tools would have made predictable routes even more valuable, reinforcing the idea that these early groups planned movement with efficiency and safety in mind.

6. Movement pace indicates controlled travel under load.

Footprint spacing provides insight into how fast these individuals were moving. The steps are evenly spaced, neither rushed nor staggered, suggesting a steady walking pace. The drag marks maintain consistent depth without sudden gouges or skips, which would appear if loads were dropped or pulled erratically.

This controlled movement fits hauling rather than fleeing or hunting. Dragging weight requires balance and rhythm. The preserved pace shows calm, purposeful travel, indicating these were routine journeys rather than emergency movements.

7. The evidence pushes technology timelines backward.

Traditional views place transport technology far later in human history, often tied to wheels or animal domestication. The White Sands tracks suggest that humans were solving transport problems tens of thousands of years earlier using simpler methods. This reframes technology as a spectrum rather than a sudden leap.

Recognizing that dragging loads is a mechanical solution changes how early innovation is understood. It shows that technological thinking existed long before complex tools, rooted in observation, experimentation, and daily necessity.

8. Similar dragging methods persisted across cultures.

Ethnographic records show that dragging devices like travois remained in use across North America into recent centuries. Even after animals were domesticated, many groups continued to rely on dragging tools because they were adaptable and effective in varied terrain.

The continuity of this method suggests it worked exceptionally well. The White Sands tracks may represent an early chapter of a technology that proved so practical it survived for thousands of years across changing cultures and environments.

9. The tracks capture ordinary life, not rare events.

What makes these findings powerful is their everyday nature. These were not ceremonial paths or extraordinary constructions. They reflect routine movement, family travel, and problem solving embedded in daily life. The people who made these tracks were not inventing for glory, but for survival.

By preserving a moment of ordinary travel, the site offers a rare glimpse into how early humans lived, moved, and adapted. It shows innovation happening quietly, step by step, across a landscape that demanded it.