Physicists found a loophole in the usual rules.

In early 2025, a team working at Brown University reported experimental evidence for an exotic quasiparticle called a fractional exciton inside a carefully engineered graphene device. It is not a free particle you can bottle, it is a collective behavior that appears only under extreme conditions, very low temperatures and very strong magnetic fields. Still, its existence and its strange quantum statistics are forcing researchers to rethink how neutral excitations are supposed to behave in some of the most correlated materials ever built.

1. A neutral excitation is behaving like it has rules.

The surprise begins with a basic expectation. Excitons are usually neat, neutral pairs, an electron bound to a hole, and they tend to behave in a boson like way that makes theorists comfortable. In the new experiments, the neutral object that forms does not sit politely in that box. It emerges in a fractional quantum Hall setting, where charge itself can split into fractional pieces, and the resulting exciton can inherit that oddness.

What makes this challenging is the reported quantum statistics. Instead of behaving purely like a boson, the excitation shows traits closer to the in between category researchers associate with anyonic behavior, even though it remains overall neutral. The setup used bilayer graphene separated by hexagonal boron nitride and tuned with gates under huge magnetic fields, as reported by Physics World.

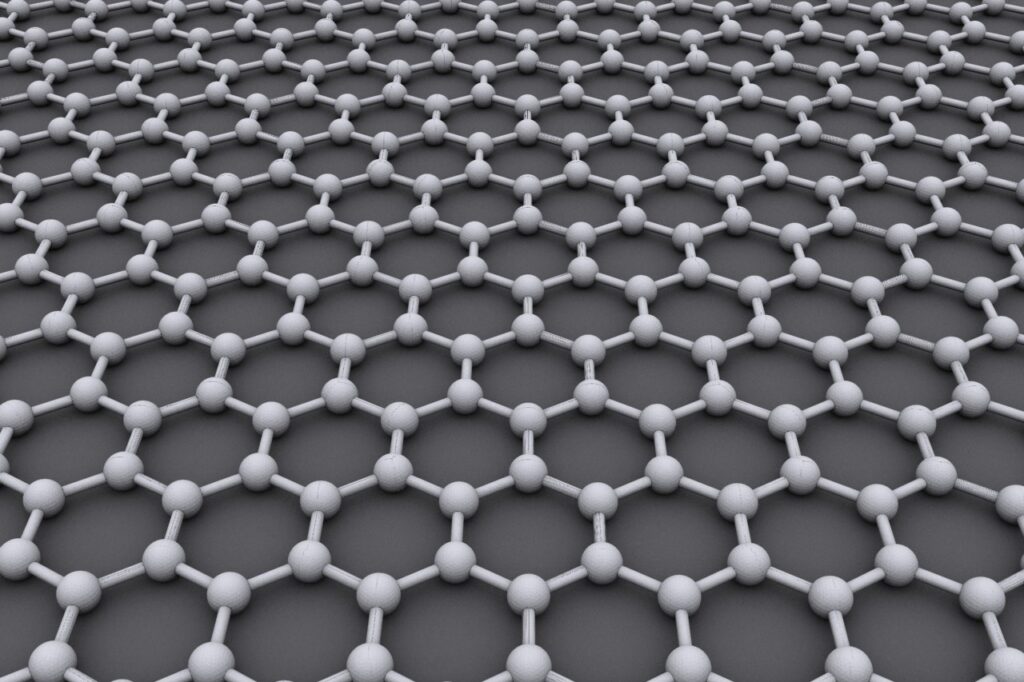

2. Graphene bilayers became the stage for rarity.

If you want strange quantum behavior, you build a system where electrons cannot ignore each other. The Brown group fabricated two atom thin graphene layers with an insulating spacer, then used electrostatic gates to tune the density and balance between layers. Under very high magnetic fields, the electrons organize into fractional quantum Hall states, and that is where exotic collective excitations become possible.

Inside that regime, the team looked for transport signatures consistent with excitonic pairing, meaning evidence that an electron in one layer and a hole like absence in another layer are binding in a way shaped by fractionalization. The headline claim is not that excitons exist, it is that an exciton made from fractionally charged constituents can appear and act unlike the standard bosonic picture. The work was described in Nature in January 2025.

3. Fractional charge pairing finally moved off the page.

For years, fractional excitons were an idea with lots of theory and not much direct experimental grounding. The barrier was practical. You need the fractional quantum Hall effect, you need clean devices, you need careful control of layer imbalance, and you need measurements sensitive enough to pick up a neutral excitation indirectly through how it changes the electronic state around it.

What shifted is that the new study links specific patterns in transport to excitonic pairing that coexists with fractional quantum Hall states, and it maps transitions between distinct phases as experimental knobs are turned. That kind of phase level evidence is what forces theory to either expand or get specific about what it cannot explain. The authors also discussed unusual statistics for some excitons in their arXiv preprint titled Excitons in the Fractional Quantum Hall Effect.

4. The usual boson versus fermion story is getting crowded.

Physics education trains everyone on two tribes. Bosons like to pile into the same state, fermions refuse to share. Many emergent excitations in condensed matter fit into one camp well enough that we can build intuition and move on. Fractional quantum Hall systems are where that comfort goes to retire.

The new fractional exciton result adds pressure because it is neutral yet may follow unconventional statistics shaped by the underlying topological order. In plain terms, the bookkeeping rules that determine how identical excitations can be swapped or braided may not match the simple categories. That pushes researchers to describe the excitation in a more topological language, where what matters is not just charge but the structure of the many body wavefunction it lives inside.

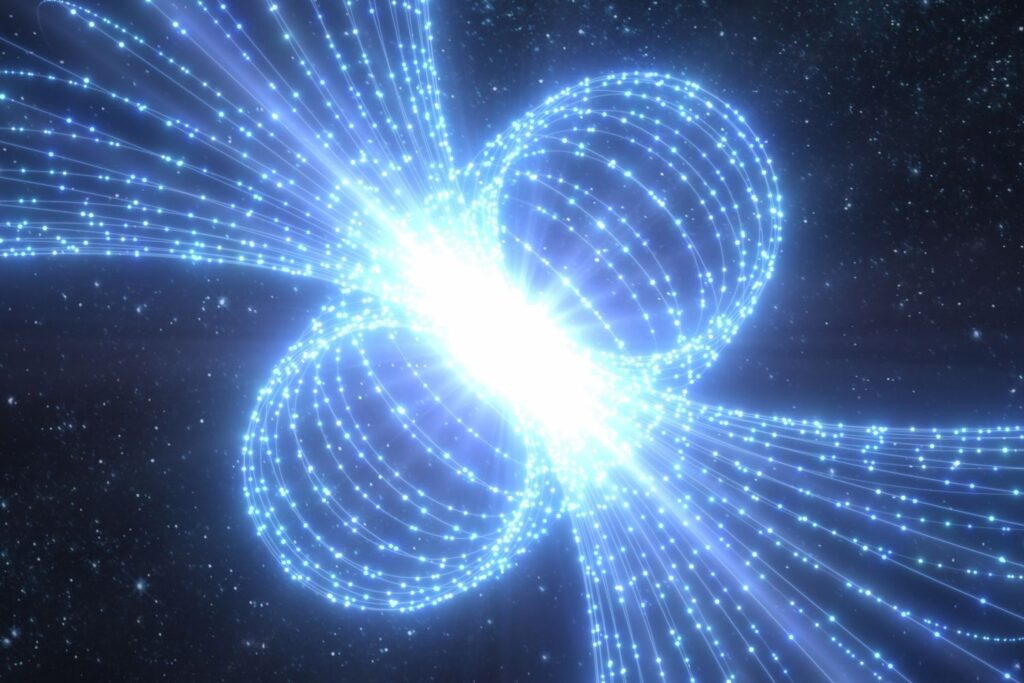

5. The magnetic field is not background scenery.

The extreme magnetic field is doing heavy work here. It forces electrons into quantized Landau levels, shrinking their kinetic freedom so interactions dominate. When interactions dominate, electrons can self organize into states where the effective excitations carry fractional charge, and the system’s response becomes quantized in fractions instead of integers.

That environment is exactly where a fractional exciton can form. An exciton usually feels like a tidy pair, but in this regime the constituents can behave like fractionally charged quasiparticles rather than ordinary particles. The magnetic field, combined with ultracold temperatures, creates a narrow window where these collective modes are stable enough to influence measurable transport. The point is not drama, it is control, the field is part of the apparatus that makes the new particle possible.

6. The experiment hints at new quantum phases.

The result is not just a single particle sighting. The researchers describe signatures consistent with phase changes as they vary filling factors and layer imbalance, meaning the overall ground state of the system can shift between distinct organized patterns. That matters because phases tell you what the system is really doing, not just what one excitation looks like.

Fractional excitons can become ingredients in these phases, lowering the energy cost of certain excitations and reshaping what counts as the simplest collective mode. In some regions of parameter space, excitonic pairing may be central to defining the state, not a minor add on. If that holds up across follow up experiments, then theories that ignore excitonic structure in the fractional quantum Hall context may have to be rewritten with excitons as first class citizens.

7. Measurement is indirect, so interpretation must be careful.

Nobody is taking a photo of a fractional exciton. The evidence comes from how the electronic system conducts, how it transitions, and how its quantized behavior shifts under controlled tuning. That means the experimental argument depends on ruling out more ordinary explanations, like disorder effects, heating artifacts, or alternative quasiparticle rearrangements.

This is where the story becomes tense in the scientific way. You want consistency across devices, robustness across sweeps, and scaling that matches a specific theoretical picture. A neutral excitation can hide inside the data unless its fingerprints are sharp. The claim challenges theory only if the interpretation survives replication and sharper probes, including complementary techniques like spectroscopy in related platforms. The early result is powerful, but the next papers decide how far it reaches.

8. Anyonic style behavior keeps leaking into new places.

Anyonic statistics are often introduced as a special feature of two dimensional systems, especially fractional quantum Hall states. They sit between bosons and fermions and show up in the math of braiding, where swapping two excitations can change the quantum state in a way that depends on the path taken. It is already strange, and now it is spreading into discussions of neutral modes.

If fractional excitons truly inherit unconventional statistics, that widens the cast of excitations that might be useful for topological ideas in quantum information. Neutral particles are attractive because they can be less sensitive to certain kinds of noise, but they are also harder to control. The deeper point is that statistics are not just labels. They influence what phases can exist, how excitations interact, and what kinds of stable operations a system can support.

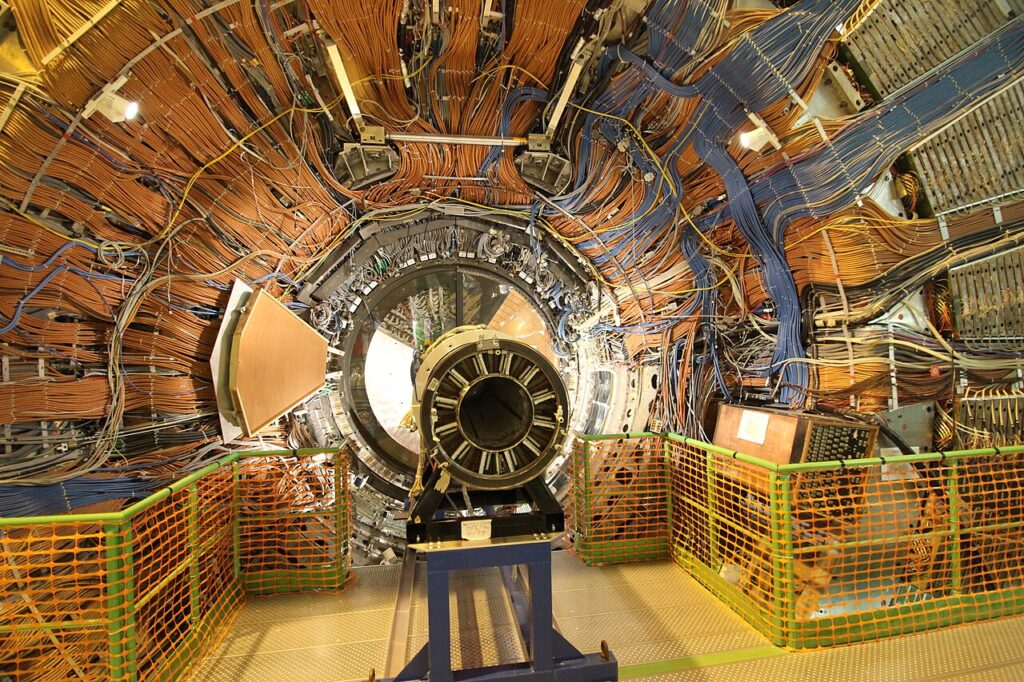

9. Device engineering is becoming the new particle accelerator.

High energy physics smashes particles together. Condensed matter builds tiny landscapes where particles are forced to act new. Graphene stacks, moiré patterns, and ultra clean interfaces are now producing excitations that were once theory toys. The fractional exciton fits that pattern, it exists because the device is clean enough and tunable enough to push electrons into an interaction dominated corner.

The practical takeaway is that materials science is now part of fundamental physics. By changing the spacing between layers, the dielectric environment, and the gate geometry, researchers can adjust how strongly quasiparticles feel each other. That makes it plausible that fractional excitons will not remain a one off curiosity. As labs refine fabrication, the menu of emergent excitations expands, and each new entry pressures old assumptions about what is allowed.

10. Long held models will be tested by what comes next.

Theories survive by making predictions that experiments cannot easily wiggle out of. Fractional excitons are a sharp test because they combine familiar ingredients, excitons and fractionalization, into a composite that behaves in a less familiar way. If follow up work confirms the unusual statistics and maps the phase diagram more completely, models that treat excitons as straightforward bosons in these settings will look incomplete.

What researchers will watch next is reproducibility across different samples, consistency under different tuning paths, and evidence from independent measurement techniques that point to the same underlying excitation. If the picture holds, it does not just add a new particle to a list. It changes how physicists describe neutral collective modes inside topological phases, and that can ripple into how future quantum materials are designed and used.