One stubborn paragraph still refuses to settle.

In libraries and lecture halls, the biggest arguments are not always about miracles, they are about manuscripts. One short passage, copied and recopied across centuries, keeps pulling historians back to the same question: what can we responsibly say about Jesus as a real person in first century Judea. The text is ancient, the debates are modern, and the stakes feel personal. Every generation rereads it with new tools and new suspicions, which is why the question never quite stops moving.

1. A few lines in Josephus changed everything.

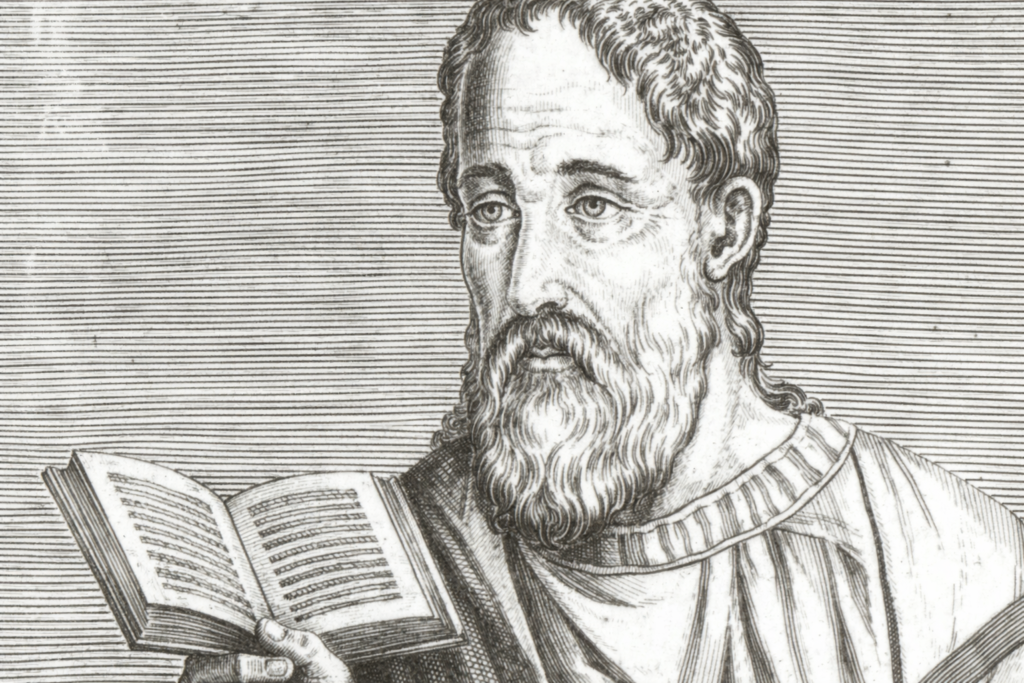

The contested text is the Testimonium Flavianum, a paragraph in Antiquities of the Jews written by the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus in Rome around AD 93. In its received form, it describes Jesus as a wise man, mentions followers, and places his execution under Pontius Pilate. Those details hit like a thunderclap because Josephus was not a Christian author and he wrote within living memory of the early movement.

The fight begins with the tone. Parts of the wording sound too friendly to Christianity for a Jewish writer loyal to Rome, and scholars have long argued later scribes polished it. Josephus matters because he is one of our best external historians of the period, as stated by Encyclopaedia Britannica. That single paragraph becomes a pressure point for everything we want ancient sources to be.

2. The argument hinges on what Josephus would say.

Even people who accept a historical core often suspect a later editor added devotional phrases. The most famous problem is the line that reads like a confession, that he was the Christ. That is not impossible, but it is culturally awkward for Josephus, who wrote as a Jewish priest and historian, not a believer writing testimony.

So scholars approach it like a crime scene. They compare Josephus’s usual vocabulary, his rhythm, and how he normally describes messianic claimants. They also check how the paragraph fits into the surrounding story about unrest under Pilate. Some reconstructions keep a neutral report and peel off the most Christian sounding phrases. The result is a paradox. The more you trim, the more plausible it sounds, yet trimming is itself an act of interpretation, as reported by Oxford Bibliographies. That tension keeps the question alive because no edit feels fully safe.

3. Christian writers quoting it create fresh suspicion.

The earliest clear quotation of the Testimonium in surviving literature comes from Eusebius of Caesarea in the fourth century, a Christian historian with every reason to love an outside reference to Jesus. That timing immediately makes skeptics twitch. If the text is so useful, why does it not show up earlier in Christian apologetic writing more loudly and more often.

Supporters of partial authenticity answer that early Christians may not have had broad access to Josephus, and the original wording may have been too neutral to be a great weapon in debate. Critics answer that neutrality does not stop people from quoting helpful lines, especially in theological disputes. This is why the passage functions like a mirror. It reflects not just what Josephus wrote, but what later communities wanted him to have written, according to Biblical Archaeology Society. The quote history becomes part of the evidence.

4. Textual criticism turns tiny phrases into clues.

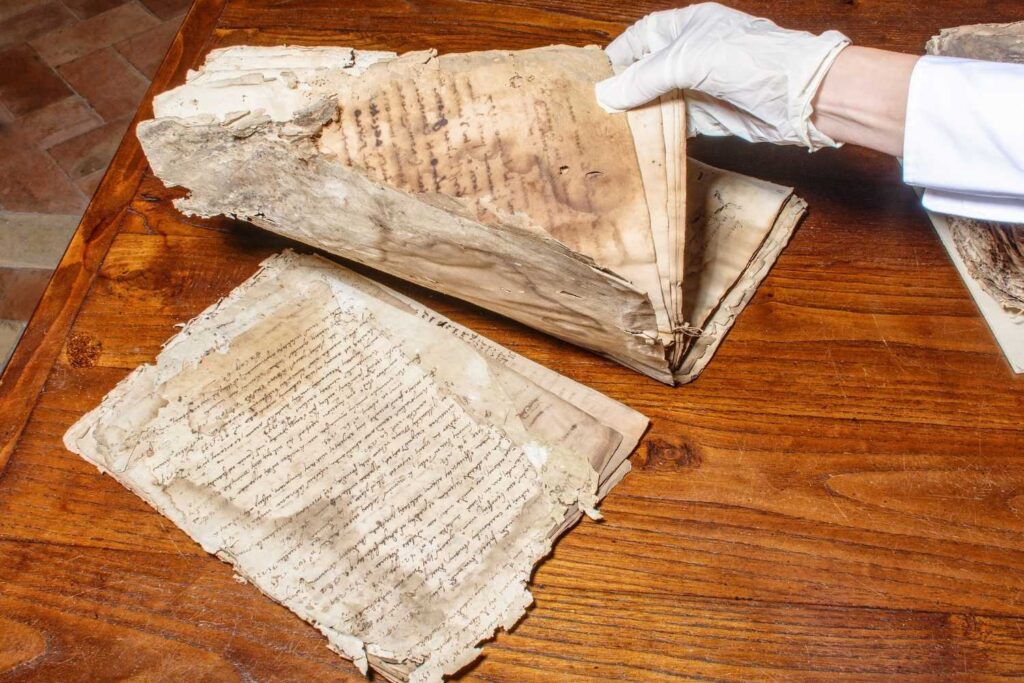

Once you accept that scribes altered texts across centuries, every adjective becomes suspicious. Scholars look for seams, words that do not match Josephus’s normal style, and claims that feel like later creedal language. They also compare how Josephus describes other figures to see whether Jesus is being singled out in an unusual way.

That work can feel maddeningly granular, yet it is the only way to handle ancient literature responsibly. Ancient manuscripts were copied by hand, often by people with motives that ranged from pious to practical. A scribe could smooth a sentence for clarity or tilt it for theology. When you are dealing with a paragraph that might have been edited in stages, the question becomes less about forgery and more about layers. The reason the debate never dies is that the evidence itself is layered too, and layers invite interpretation.

5. A second Josephus passage complicates the story.

Josephus also mentions James, described as the brother of Jesus who was called Christ, in Antiquities Book 20 during a narrative about the high priest Ananus. This reference is shorter, less theological, and often treated as more stylistically Josephus. It can feel like a calmer witness in the middle of a shouting match.

That matters because it changes the burden of proof. If Josephus knew enough to identify Jesus as the figure connected to James, then a brief mention elsewhere is not bizarre. It also makes the Testimonium less lonely. Instead of one suspicious paragraph, there are multiple touchpoints in the same author. Still, even this passage gets debated, mostly around the phrasing and whether a later hand slipped in a clarifying label. The effect is that Jesus stays in the historical frame, but always with footnotes attached.

6. Roman sources add weight but not comfort.

When historians step outside Jewish texts, they often point to Roman writers such as Tacitus, who describes Christians in Rome and notes that Christus was executed under Pontius Pilate. That sounds firm, yet it also opens new questions. Did Tacitus verify this independently, or did he repeat what Christians in Rome already said about themselves.

The debate is not only about whether Jesus existed. It is about what kind of information ancient elites had access to and how they used it. Romans recorded executions, but bureaucratic archives rarely survive, and historians often relied on prior works and public rumor. So even when you add Roman testimony, you are still dealing with transmission and memory, not a modern police report. The contested paragraph in Josephus stays central because it sits closer to the cultural and geographic setting of Judea, which keeps pulling scholars back to it.

7. Translation choices can quietly change the meaning.

Most readers encounter these texts in translation, and translation can steer interpretation without anyone noticing. Words like wise man, doer of startling deeds, or leading men can carry different shades depending on how they are rendered from Greek. A translator can make Josephus sound skeptical, neutral, or faintly admiring without changing the basic content.

That matters because small tonal shifts affect larger arguments about authenticity. If the paragraph reads like a Christian confession, suspicion rises. If it reads like a detached notice about a controversial teacher, it feels more plausible. Translation also interacts with theology, because modern readers bring their own assumptions to loaded terms. When a debate depends on whether a phrase sounds too Christian, the sound of the phrase becomes evidence. That is why scholars often insist on reading the Greek carefully, and why popular summaries can mislead by smoothing out the very roughness that scholars are trying to measure.

8. The stakes include politics, identity, and memory.

This is not a purely academic squabble. For believers, a non Christian reference can feel like a historical anchor. For skeptics, the same reference can feel like a manufactured prop. For historians, it is a test case in how fragile ancient evidence can be and how easily modern desire shapes conclusions.

The politics of late antiquity also haunt the debate. As Christianity gained power, copying practices changed, institutional priorities shifted, and texts were preserved by communities with theological commitments. That does not automatically mean corruption, but it does mean context. The question of Jesus stays alive partly because the evidence sits inside human institutions, and institutions have agendas. Every time someone asks for an outside source, the Josephus paragraph returns to the center, and the argument resets with new energy.

9. Modern technology keeps reopening old manuscripts.

Digital imaging, spectral photography, and manuscript databases have changed what scholars can do with ancient texts. Faded inks can be recovered, palimpsests can be re read, and small variations across manuscript families can be compared at scale. That does not magically solve the Testimonium, but it changes the temperature of the debate.

When new readings appear or a neglected version is re examined, people feel the ground shift again. Scholars can also test how phrases travel across time, whether certain wording appears only after specific centuries, and how scribal habits vary by region. The result is a constant sense that the next technical advance might clarify something that has been stuck for generations. Even when nothing definitive changes, the process keeps the question active, because the tools keep improving and the archive keeps yielding surprises.

10. Future finds could change what counts as evidence.

The most unsettling possibility is not that the Testimonium gets resolved, but that it gets overshadowed. New papyri from Egypt, newly read scrolls from Herculaneum, or a forgotten chronicle in a monastery collection could provide fresh context for first century Judea and early Jesus movements. Scholars already know that huge caches of ancient texts still wait in fragments, unedited and untranslated.

If a new independent source emerged that clearly referenced Jesus, Pilate, or early followers in Judea, the entire debate would shift from one contested paragraph to a broader evidence web. That is why the question stays alive. The archive is not closed, the technology is accelerating, and historians have learned the hard way that one small text can redraw the map. The Testimonium is still the headline, but it may not be the last surprise.