A sorrowful and complex tale of early America.

Early North American history usually highlights conflict, ambition and settlement, yet beneath those familiar narratives sits a quieter thread about Europeans who stepped away from colonial life entirely. Some choices were voluntary while others were shaped by fear, hardship or unexpected bonds. As historians uncover richer records, these disappearances reveal that cultural lines were never as fixed as textbooks suggested. Many who left did so because the world they found beyond the settlements offered connection, meaning or survival in ways the colonies could not. Understanding those decisions adds weight to a story that is far more human than myth.

1. Some settlers left because Indigenous societies offered stability.

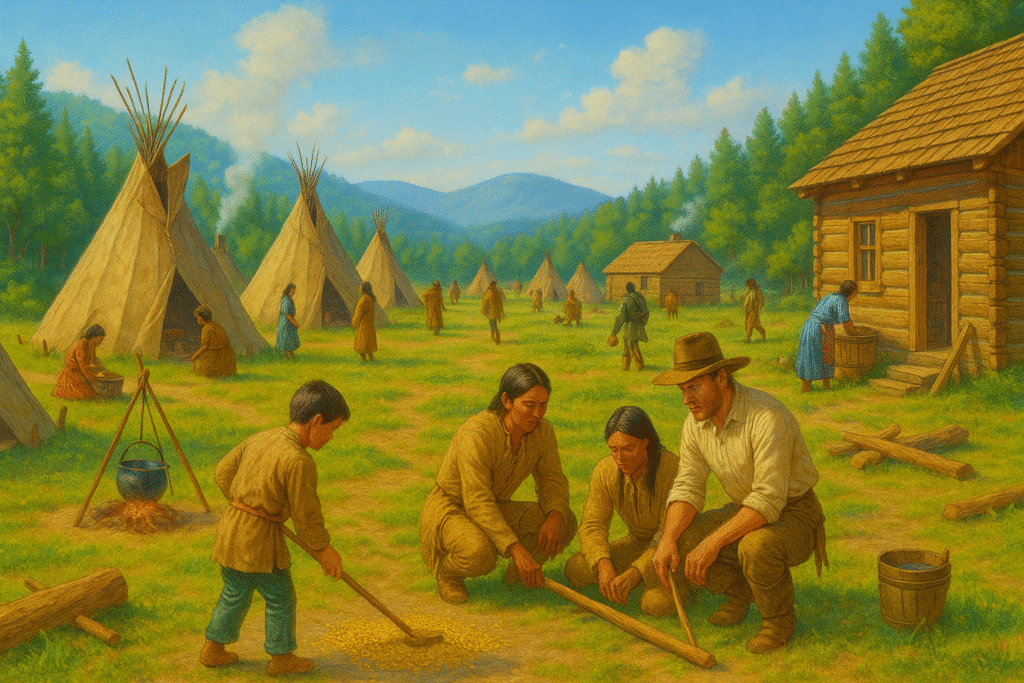

Fragile colonial outposts often struggled with food shortages, leadership disputes and unfamiliar terrain that turned daily life into a series of exhausting gambles. Scholars have noted that Indigenous communities had long built systems that matched their environment, including farming practices and trade networks that provided steadier routines, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Facing shortages or disappointment, some settlers naturally gravitated toward societies that appeared more functional and resilient than their own.

As newcomers found roles inside these communities, a sense of belonging slowly replaced uncertainty. Relationships strengthened, responsibilities formed and the pressure of colonial life slipped further away. The draw of security and social coherence made returning to European settlements far less appealing, setting the stage for the next set of reasons people drifted into Native life.

2. Others vanished into tribes after captivity reshaped their loyalties.

Captivity varied sharply from one experience to another, yet many accounts show that some captives were adopted into families and offered emotional and physical safety they had not felt before. These new relationships could become deeply meaningful, especially when colonial life had failed them, as stated by a detailed historical review from the University of Pennsylvania. Over time, individuals who were welcomed into Indigenous communities often felt more rooted there than in the places they had originally come from.

When the chance for release came, not all wanted to go. Returning meant reentering a world marked by instability and harsh expectations. Remaining with the people who had fed them, protected them and cared for them felt natural, and that shift in allegiance nudged many toward permanent belonging.

3. Intermarriage drew settlers into Indigenous worlds permanently.

French traders and frontier families frequently formed marriages with Indigenous partners, creating bonds that blended economies, households and cultural practices. These relationships emerged from trust built through years of cooperation, a pattern reported by the National Park Service. Marriage brought settlers directly into Native kinship systems, giving them relatives, obligations and social positions that carried more permanence than anything available in the unstable colonies. Over time, these marriages anchored people to their new communities in ways that made leaving increasingly unthinkable.

Children raised within these families deepened the connection. They spoke Native languages, followed community traditions and saw their world through lenses shaped by both parents but grounded in Indigenous life. For many settlers, watching their children grow into this identity sealed the decision to stay, opening the door to other motivations for disappearing.

4. Some settlers sought escape from rigid colonial hierarchies.

Strict religious rules, harsh governance and limited social mobility made early settlements difficult places for those who felt stifled or mistreated. Indigenous societies often operated with different forms of leadership that emphasized councils, dialogue and collective responsibility rather than rigid authority. Settlers who struggled with colonial expectations found these approaches refreshing and surprisingly compatible with their own need for breathing room.

When they stepped into these new rhythms, many discovered that freedom felt more attainable within Native communities. Daily life allowed for greater individuality and fewer punitive constraints. This shift in social experience helped shape a sense of belonging that gradually overshadowed any obligation to return.

5. Trade alliances gradually pulled individuals into Native cultures.

The fur trade created long seasons of shared work where Europeans lived among Indigenous families for months at a time. These interactions fostered trust, familiarity and a sense of mutual dependence that grew stronger with every year. Traders learned languages, traveled traditional routes and absorbed customs that quietly reshaped how they understood the world. Choosing to remain became less like a decision and more like a continuation of the life they were already living.

As these economic partnerships deepened, emotional and cultural ties followed. Individuals came to see Native communities not as temporary hosts but as the people who shaped their survival and identity. With each passing season, the pull toward permanent settlement strengthened.

6. Young runaways abandoned settlements to join Native groups.

Some young colonists fled harsh apprenticeships, abusive households or rigid religious communities and sought refuge beyond the boundaries of their settlements. Indigenous groups sometimes offered them acceptance, guidance and protection that contrasted sharply with the circumstances they escaped. For these youths, the shift into Native life was often quick because they had already rejected the constraints of colonial society long before they ran.

Once welcomed, many found a sense of support they had never known. Their new communities provided structure without cruelty and expectation without fear. What began as a desperate escape gradually turned into a meaningful attachment, shaping a life that felt more fitting than the one they left behind.

7. People fleeing punishment disappeared into tribal networks.

Colonial justice systems imposed severe penalties even for minor offenses, and those facing harsh consequences often saw the surrounding wilderness as their only escape. Some of these individuals fled into Indigenous territories, where existing alliances or trade familiarity made seeking refuge possible. Native communities occasionally offered protection to runaways who demonstrated willingness to contribute and adapt. For people who feared imprisonment, debt bondage or corporal punishment, disappearing into Native life felt like the only path toward safety and autonomy.

As these individuals rebuilt their lives, they often discovered a degree of acceptance that contrasted sharply with the judgment they left behind. Their new roles within the community allowed them to be valued for their skills rather than defined by their past mistakes. With trust growing over time, the idea of returning to a society that had threatened them lost any appeal. These transformations made permanent assimilation not only feasible but preferable.

8. Missionaries experienced unexpected cultural reversals.

Missionaries arrived with clear goals and unwavering certainty about their purpose, yet extended time among Native peoples often challenged those assumptions. Some missionaries found themselves drawn to the social harmony, interconnectedness and spiritual depth they observed in daily life. While their intent had been to influence Native communities, long exposure sometimes reversed that direction, quietly reshaping their own loyalties. When a missionary built strong bonds, the lines between teacher and learner blurred.

Those who chose to remain rarely described their decision as turning away from their work. Instead, they viewed their new relationships as an evolution of purpose shaped by lived experience. Returning to colonial towns often felt dissonant because the life they built within Indigenous society offered a sense of belonging the settlements never had. This shift paved the way for others who followed similar paths of unexpected transformation.

9. Multilingual settlers acted as bridges between cultures.

Interpreters played essential roles in diplomacy and trade, moving between worlds with rare fluency. Over time, many of these multilingual settlers became deeply embedded in the communities they worked with. Their daily interactions meant they understood not just words but values, humor and unspoken norms. With each season, their connection to Indigenous life strengthened until the identities they carried became intertwined. For many, staying felt like a natural extension of their work rather than a dramatic leap.

As relationships deepened, the distinction between interpreter and community member faded. These individuals built trust that made them essential to tribe-settler interactions while also giving them meaningful positions within Native life. Once those bonds were established, returning to European settlements meant losing a world in which they felt indispensable. The pull of belonging outweighed the familiarity of their origins.

10. Disillusioned settlers found meaning in Indigenous worldviews.

Some colonists arrived with hopeful expectations about opportunity and community, only to find the colonies riddled with inequality, exploitation and rigid social structures. When they encountered Indigenous cultures centered on reciprocity, land stewardship and collective responsibility, many felt an immediate resonance. These values offered a more grounded way of living that contrasted sharply with the moral and economic pressures of colonial life.

Adopting these worldviews often led settlers toward a deeper sense of purpose. The shift was not abrupt but accumulated through countless conversations, shared meals and observations of balanced community life. When the contrast became impossible to ignore, the desire to return to colonial society faded. What began as quiet admiration often grew into full integration.

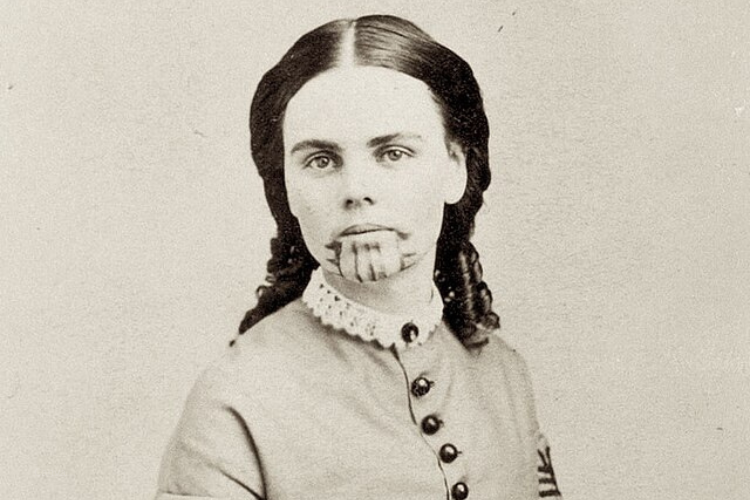

11. The story of Olive Oatman reminds us that not all disappearances ended well.

Olive Ann Oatman’s ordeal reflects a far harsher side of cultural crossing. After her family was attacked in 1851 during their journey west, she was taken first by one group and later adopted by the Mohave. Her sister died in captivity, and Olive endured years of profound loss and adaptation. She eventually returned to white society carrying the Mohave chin tattoo, a symbol of both belonging and survival. Her story reminds us that disappearance into Native America sometimes came through tragedy rather than choice.

Her experience captures the emotional weight behind these histories. The bonds she formed were real, yet they grew within circumstances marked by violence and grief. Stories like hers reveal that the movement between cultures was never one-dimensional or uniformly positive. These complex paths remind us that disappearance could mean refuge, transformation or deep trauma, depending on who lived it.