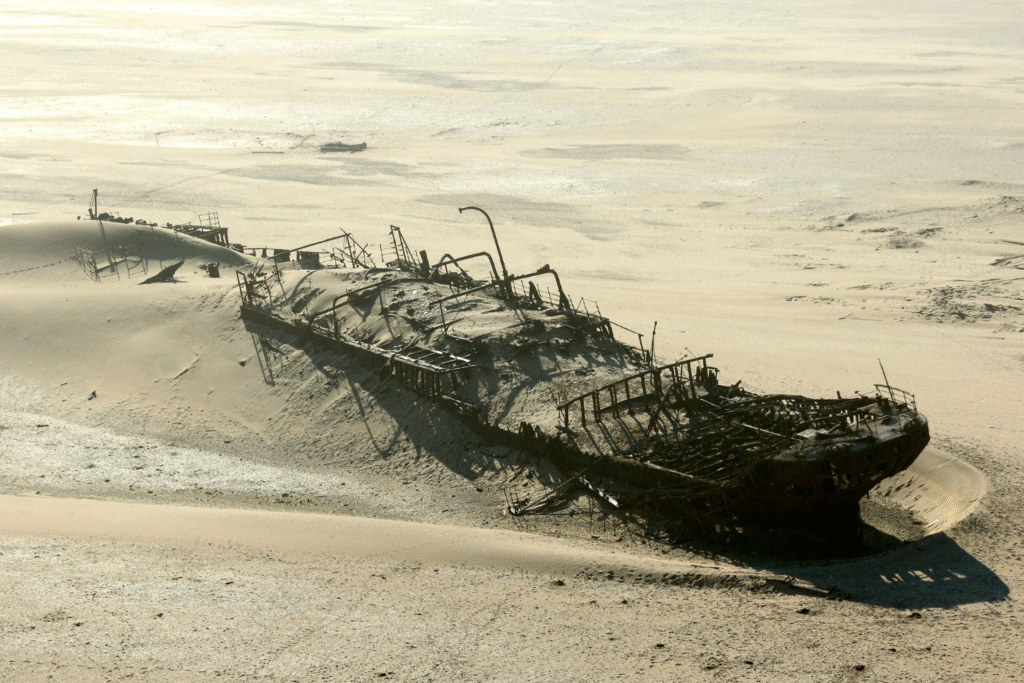

An astonishing find beneath desert sands signals history uncovered.

A remarkable maritime time capsule has emerged along Namibia’s coastline where a vessel believed to have sunk nearly 500 years ago has been uncovered remarkably intact and potentially laden with treasure. What started as a routine mining operation morphed into a full-scale archaeological wonder that challenges our understanding of early global trade, shipbuilding, and colonial voyages. As the story unfolds it invites us to imagine the ship’s final journey, the treasures it carried, and the centuries it waited to be revealed.

1. The wreck is identified as a Portuguese ship from 1533.

Scholars traced the vessel to the Bom Jesus, a Portuguese ship that set sail from Lisbon in March 1533 and never reached its destination. The identity was established after teams discovered coinage, copper ingots, and archival links matching that date and origin, as stated by The Jerusalem Post. Its abandonment and subsequent burial beneath shifting sands now illuminate a key moment of early-modern maritime history. With its Portuguese origin confirmed, the wreck becomes more than a relic, it becomes a chapter in the Age of Discovery, bridging Europe and Africa in a tangible way.

2. The cargo appears to include thousands of gold coins and copper ingots.

The excavation revealed approximately 2,000 gold coins plus tens of thousands of pounds of copper ingots as discovered by a publication in Marine Insight. Researchers suggest the richness of the haul speaks to how lucrative trade missions were in the early sixteenth century, and the combination of gold and copper hints at both prestige and raw commodity transport. The presence of this treasure dramatically raises the significance of the find, and suggests that the ship’s loss wasn’t simply accidental but may reflect the dangers and stakes of global navigation at the time.

3. The wreck lies remarkably well preserved beneath desert and marine sediment.

Unearthed near the Namibian coast after diamond miners drained a lagoon, the ship’s remains lie in remarkable condition, shielded from usual marine degradation. As reported by Numismatic News, the unique preservation owes much to the copper-rich cargo and the geomorphology of the surf zone, which prevented many organisms from degrading the wood. This state of preservation opens up rare opportunities for understanding ship construction, cargo stowage, and voyage conditions of the early sixteenth century. Moving from discovery to study, archaeologists now have a near-complete snapshot of a lost voyage.

4. The finding rewrites our knowledge of early Portuguese maritime routes.

Rather than sinking on the high seas, evidence suggests the ship grounded or capsized close to shore, then became buried under layers of sediment and sand. That scenario challenges assumptions that lost treasure ships always went to deep ocean graves. In this case the proximity to land, the desert transition, and the mining interference all combined to keep the wreck hidden until modern times. Researchers are now rethinking the security of coastal navigation routes and the hazards that early vessels faced—even in near-shore waters once thought less risky.

5. The site is located in a restricted diamond mining zone.

The discovery occurred within the Sønderorp region of Namibia’s Sperrgebiet, a long-restricted diamond mining area. Because of this unusual jurisdiction, archaeologists had to navigate complex cooperation between mining firms, the government and conservation teams. The overlap of treasure hunting, mining interests and heritage preservation creates tension and opportunity in equal measure. Access constraints may slow full excavation, but they also mean that the site has remained undisturbed longer than many wrecks, preserving context and artefacts in situ.

6. The cargo’s mix of treasure and trade goods highlights global commerce.

Beyond gold coins, the ship carried copper ingots, musket parts, artillery components, and trade goods destined for eastern markets. This mixture shows that the voyage was not purely about bullion but also about industrial and military commodities. Understanding the assemblage helps researchers reconstruct the supply chains and economic networks of the sixteenth-century Portuguese empire. The fact that both prestige items and raw materials were aboard signals how intertwined luxury trade and extractive commerce were even then.

7. Conservation and excavation are underway under challenging conditions.

Working in shifting sands, surf zones and desert-adjacent terrain, archaeologists face a logistical maze: drying out waterlogged timbers, documenting fragile metal artefacts, and protecting the site from looters. The preservation of the cargo thanks to its copper ballast means the work must proceed carefully to avoid rapid degradation upon exposure. Teams are applying state-of-the-art maritime archaeology techniques to ensure that when these materials are lifted into the modern world they carry as much context as they do mystery.

8. The discovery could transform public engagement with maritime history.

With its dramatic story and tangible treasures, the wreck offers potential for museum displays, heritage tourism and public learning in Namibia and beyond. The interplay of narrative—of a ship lost for centuries, found by miners, and now being studied—resonates deeply with contemporary audiences. If managed responsibly, the site may become a bridge between academic research and popular imagination, turning an archaeological event into a story that connects past and present.

9. The find invites questions about ownership, ethics and heritage.

Who owns the treasure? Who benefits from the discovery? The wreck raises complex questions about cultural heritage, colonisation, and resource control. Namibia’s government, mining companies, Portuguese heritage agencies and global archaeology institutions all hold stakes. Beyond the glitter of gold there is a story about power, history and memory—one which forces us to ask whose history is unearthed, whose voice carries, and how we tell the story of global trade through a single hull buried beneath sand.