Scientists have discovered that ants may be medicine for feathers.

When a crow or jay sprawls on an ant hill, wings spread wide and feathers ruffled, the scene can look unsettling. At first glance, it seems like a bird in distress, surrendering itself to stings. Yet this behavior, known as “anting,” is deliberate. The birds aren’t weak—they’re self-medicating.

For decades, ornithologists dismissed it as odd ritual. Now, researchers suggest ants provide a chemical defense. Their formic acid, released when threatened, has antifungal and antibacterial properties. That makes ant hills a kind of natural pharmacy, especially valuable for sick or parasite-ridden birds. It’s a survival strategy hiding in plain sight, one that stretches across species and continents. And it shows how animals sometimes discover remedies long before humans write them down.

1. Anting is a deliberate act, not random behavior.

Birds engage in both active and passive anting, and both show intent rather than chance. Active anting happens when a bird picks up individual ants and rubs them across its feathers. Passive anting looks stranger—birds collapse onto a nest, flaring wings as if surrendering. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, this behavior has been documented in over 200 bird species, from songbirds to corvids.

That detail alone changes how it’s interpreted. Instead of a sign of weakness, it becomes a conscious routine. Sick birds, in particular, seem to seek it out more frequently. Rather than mere instinct, it looks like an example of birds actively managing their health. From the outside, it may look chaotic. From the bird’s perspective, it’s treatment.

2. The formic acid ants release works like a natural disinfectant.

The scientific key lies in chemistry. When ants feel threatened, they spray formic acid, a compound with strong antibacterial and antifungal qualities. Studies have shown that birds covered in these secretions reduce external parasites, including mites and lice. This is why many ornithologists frame anting as self-medication rather than random play, as reported by the Journal of Avian Biology.

The acid doesn’t just burn off pests—it can reduce the spread of feather fungi that weaken plumage. In other words, ants aren’t just nuisances to birds. They’re accidental pharmacists, providing a natural wash that humans only began to study seriously in the last century.

3. Crows have turned anting into an unmistakable ritual.

Few birds dramatize the behavior quite like crows. Field studies describe them stretching across mounds, eyes half-shut, as if in a trance. Researchers point out that corvids seem unusually persistent with anting, often repeating it for long stretches. This makes sense, since they are both intelligent and social, passing behaviors across groups, as discovered by National Geographic field surveys.

The persistence may be why crows are so often used as examples of avian intelligence. They don’t just stumble into health tricks—they appear to refine and share them. Watching crows anting, you get the sense they know exactly what they’re doing, and they’re not rushing the process.

4. Jays sometimes use ants like brushes.

Blue jays have been spotted collecting ants and sweeping them deliberately across their wings. The motion looks almost like grooming with a tool. By using ants this way, jays combine their meticulous grooming habits with chemical defense, layering one strategy over another.

This behavior also blurs the line between tool use and instinct. Birds already preen obsessively, but adding ants into the mix suggests conscious improvement. Some biologists believe jays, like crows, pass along this behavior through observation. In suburban backyards, it’s one of those moments that looks like a quirk but is really biology in action.

5. Sick birds are the most determined to ant.

Healthy birds may occasionally collapse on an ant hill out of habit, but sick birds show a different intensity. Observers note longer sessions and repeated visits, sometimes returning to the same colony over days. It hints at instinct steering them toward relief when their immune systems falter.

For a sick bird, preening alone isn’t enough. Ants provide something stronger—a chemical coating that buys time against parasites or infection. The sight may look desperate, but it’s precisely the opposite. It’s a strategy for survival, one that bridges instinct and necessity.

6. Anting often follows heavy molting seasons.

When birds shed old feathers, their skin becomes more vulnerable to mites and fungal infections. Anting spikes after molting, suggesting that birds recognize when their defenses are lowest. By lying across a nest of ants, they coat sensitive new growth with a protective layer.

This isn’t just about comfort, it’s about maintaining flight efficiency. Weak feathers mean slower escapes and higher risk of predation. Anting after molting is another way birds stack the odds in their favor during vulnerable times.

7. Not all ants are chosen equally.

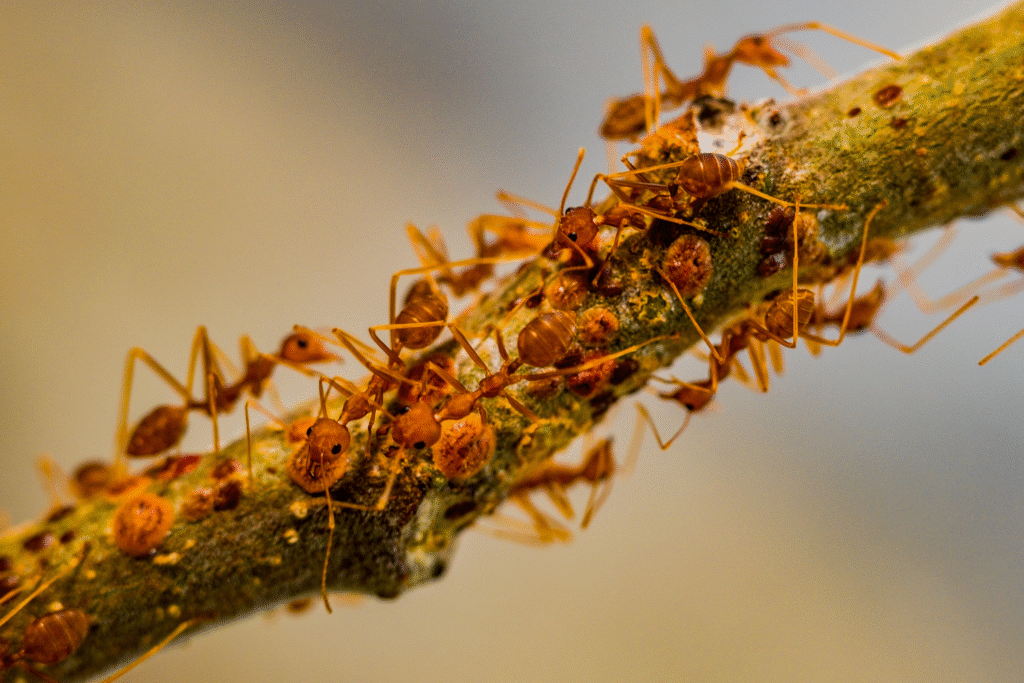

Birds show selectivity. Formicine ants, which release formic acid, are overwhelmingly preferred over other ant species. That suggests birds know which colonies provide real benefit. Watching them, researchers note that birds abandon nests of ants without the chemical spray and move on until they find the right species.

That trial-and-error persistence underscores how ingrained the practice has become. It’s not haphazard flopping—it’s targeted. The ants play a chemical role, and the birds have figured out how to sort useful colonies from useless ones.

8. Some birds swap ants for substitutes.

When ants aren’t available, certain birds have been recorded rubbing alternative irritants like millipedes, citrus peels, or even cigarette butts into their feathers. The behavior mimics anting but with whatever produces strong-smelling chemicals.

These substitutions reveal the depth of the instinct. Birds aren’t blindly attached to ants; they’re seeking chemical help. Ants just happen to be the most widespread and accessible option. In urban environments, that flexibility means birds adapt human litter into their routines, even if it’s less effective than the real thing.

9. Ornithologists still debate if comfort plays a role.

Some argue that anting may not be only medicinal. Birds often look entranced during the process, almost as if it produces a narcotic relief. The truth may be both: chemical benefit layered with sensory satisfaction.

What matters is that the behavior persists across species and regions, suggesting it delivers measurable advantages. Even if comfort is part of the draw, the survival edge explains why evolution hasn’t weeded it out. What looks odd to us is routine for them.

10. Anting shows how survival can look strange to human eyes.

To a casual observer, a bird lying on an ant hill might appear to be dying. In reality, it’s doing the opposite. It’s hacking nature to stay alive. What seems grotesque or confusing is, in fact, a chemical bath hidden in plain sight.

Anting is one of those behaviors that remind us animals have long practiced forms of medicine without laboratories or textbooks. In crows, jays, and countless other species, ants become more than insects. They’re unwitting allies in the ongoing fight for survival.