Beneath Sahara sands, an unexpected genetic story.

In a cave carved into what is now southwestern Libya, archaeologists recovered mummified remains that seemed to belong neatly within the human story. The site had long been associated with early pastoralists who lived during a greener Sahara. Yet when researchers sequenced DNA from these individuals, the results resisted familiar narratives. The genetic data did not align easily with known population histories. What emerged forced scientists to reconsider who lived in North Africa thousands of years ago and how isolated they truly were.

1. The Takarkori mummies reveal unexpected ancestry.

At Takarkori rock shelter in the Tadrart Acacus Mountains of southwestern Libya, archaeologists excavated naturally mummified remains dating to roughly 5,000 to 7,000 years ago. According to Nature, genomic analysis showed these individuals possessed ancestry distinct from sub Saharan African and Eurasian populations known from the period.

The study, led by researchers affiliated with the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, found limited genetic input from neighboring groups. Instead, the DNA suggested a long isolated North African lineage, challenging assumptions that the Sahara functioned primarily as a corridor for widespread population mixing during the African Humid Period.

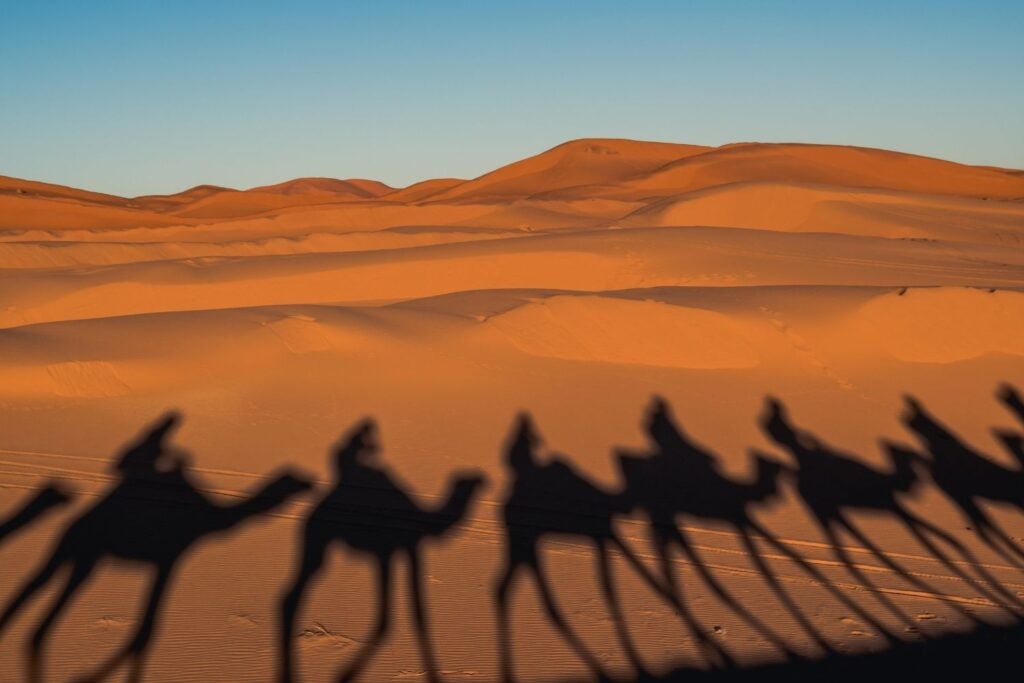

2. The Sahara was once green and habitable.

When these individuals lived, the Sahara was not the vast desert seen today. During the African Humid Period, between roughly 14,500 and 5,000 years ago, the region supported lakes, grasslands, and pastoral communities.

As reported by Science, paleoenvironmental data from lake sediments and pollen cores confirm wetter conditions across northern Africa during this era. Takarkori’s occupants were female pastoralists who herded cattle and goats, living in a landscape capable of sustaining agriculture and settlement. Their environment makes their genetic distinctiveness even more striking.

3. The burials were primarily adult women.

Excavations at Takarkori revealed multiple burials within the rock shelter, most belonging to adult women. Grave goods and associated remains indicated organized pastoral life rather than transient occupation.

As stated by National Geographic in coverage of the findings, the individuals appear to have been part of a stable herding community. Their burial context suggests social structure and ritual behavior. Yet despite cultural connections to broader pastoral traditions, their genetic profile diverged sharply from expected migration patterns.

4. Genetic isolation lasted thousands of years.

The DNA analysis revealed that these North African groups remained genetically separated for extended periods. Evidence of long term isolation emerged in the absence of substantial admixture from surrounding populations.

Even as climatic conditions supported interaction, the Takarkori community maintained distinct ancestry. This suggests social or geographic barriers that limited gene flow despite environmental connectivity across the greener Sahara. Genome comparisons indicate divergence stretching back far earlier than the African Humid Period. The lineage appears to trace to a deep North African population that persisted locally. Isolation here does not mean absence of contact, but limited genetic integration over millennia.

5. Eurasian ancestry arrived much later.

Modern North African populations carry significant Eurasian genetic influence. The Takarkori genomes indicate that this influx occurred after the period represented by the mummies.

The study places major Eurasian admixture events thousands of years later, meaning these early pastoralists predated large scale back migration from Europe or the Near East. Their lineage reflects an older North African genetic foundation. Later waves associated with Neolithic farming expansions appear absent in these individuals. This timing reshapes assumptions about when trans Mediterranean gene flow became dominant. It also separates early Saharan pastoralism from later Eurasian influenced demographic shifts.

6. Sub Saharan links were surprisingly limited.

Given Takarkori’s geographic position, researchers expected closer genetic ties with sub Saharan populations. Instead, the genomes showed minimal direct ancestry from groups south of the Sahara.

This finding complicates assumptions about north south movement during the humid phase. It suggests that ecological openness did not automatically translate into sustained intermarriage or population blending. The Sahara may have functioned as a mosaic of cultural zones rather than a seamless migration corridor. Social identity, mobility patterns, or even seasonal barriers could have limited sustained contact. The genetic boundary appears to have been maintained over centuries, not decades.

7. Pastoral life shaped community structure.

Archaeological evidence at Takarkori includes cattle remains, grinding stones, and ceramics, indicating established herding and food preparation practices.

The female dominated burial record may reflect gendered social roles within pastoral economies. These communities were not isolated wanderers but organized societies managing livestock in a once fertile Sahara. Stable isotope analysis of bones indicates diets rich in animal products, reinforcing the pastoral identity. Burial placement within the rock shelter suggests structured ritual behavior rather than casual interment. Their social world was deliberate and patterned, not primitive or transitional.

8. Climatic shifts altered migration patterns.

As the African Humid Period ended around 5,000 years ago, the Sahara began drying rapidly. Lakes receded and grasslands retreated.

Such environmental transformation likely triggered population movement toward the Nile Valley and sub Saharan regions. The genetic distinctiveness observed at Takarkori may have dissipated as groups dispersed or integrated elsewhere. Archaeological layers show reduced occupation intensity as aridity increased. Rock art in surrounding regions also declines during this transition, reflecting shrinking habitable zones. Climate pressure may have forced interaction where isolation once prevailed.

9. Ancient DNA techniques enabled the breakthrough.

Recovering usable DNA from hot climates is notoriously difficult. Advances in extraction and sequencing technology made this analysis possible.

Researchers isolated genetic material from dense bone structures that better preserve DNA in arid conditions. Without these methods, the story of Takarkori’s inhabitants would have remained speculative. Laboratory contamination controls were critical due to low endogenous DNA content. Comparative genomic datasets from Eurasia and sub Saharan Africa helped clarify ancestry placement. The breakthrough reflects both technological precision and expanding reference databases.

10. North African prehistory is being rewritten.

The Takarkori findings add complexity to North Africa’s human history. Instead of serving solely as a crossroads between continents, the region hosted populations with deep local roots.

These results challenge simplified migration models and highlight long standing diversity within Africa. The mummies do not erase connection to humanity, but they reveal a lineage that followed its own path for millennia beneath a Sahara that once looked nothing like today. Future sampling across the Maghreb may reveal additional isolated lineages. Each new genome adds resolution to a region once blurred by assumption. The desert is yielding a far older story than expected.