Ancient domestic creatures honoured in ritual burial practices.

In the world of ancient Egypt, animals were not simply companions or symbols—they were deeply interwoven into life, death and the divine. Recent studies reveal that mummified animals—ranging from cats and dogs to ibises and crocodiles—served roles as pets, offerings and sacred embodiments of gods. These discoveries invite us to reconsider how ancient Egyptians valued their animals and how this reflected broader beliefs and social structures. By exploring ten key dimensions of this practice, we uncover how mummified animals offer insight into ritual, economy and emotional lives in one of the world’s most fascinating ancient civilizations.

1. Many animals were mummified for religious offering and companionship.

The discovery of vast numbers of animal mummies across Egypt reveals that species like cats, ibis birds and dogs were treated differently than simple livestock. As reported by a Nature study, some animals were mummified as sacred offerings, pets or temple dedications. That surprises many because it shows a diversity of animal roles—from beloved companions to creatures intended to bridge earthly and divine realms. This dual function of pets and ritual players demonstrates how Egyptians did not strictly separate everyday living animals from their spiritual economy. Instead their pets could traverse both personal affection and religious obligation.

2. Some animal mummies underwent embalming processes akin to humans.

Research into embalming materials indicates that animals sometimes received treatments comparable to human mummies, as stated by National Geographic. The use of oils, linens and resins shows the embalmers applied complex techniques to certain mummified animals, signalling that the creatures held high ritual significance. When we consider that some animals were prepared with such care, we realise that the boundary between human and animal in afterlife beliefs was more permeable than assumed. This finding enriches our understanding of how Egyptians conceptualised the afterlife for animals as well as humans, and how pets may have been integrated into those systems.

3. Recent museum projects are uncovering the social lives of mummified animals.

Large-scale research efforts are now focusing on cataloguing, CT scanning and analysing animal mummies to uncover where, how and why they were created. According to the British Museum’s “Divine Creatures” project, specialists are collaborating to assess species, mummification techniques and temporal shifts in practice. These investigations are providing new windows into animal breeding, funerary economies and cult use in Egypt. By treating animal mummies as archaeological objects with social context rather than curiosities, researchers are revealing entire networks of production, use and meaning that were embedded in everyday, temple and domestic spheres.

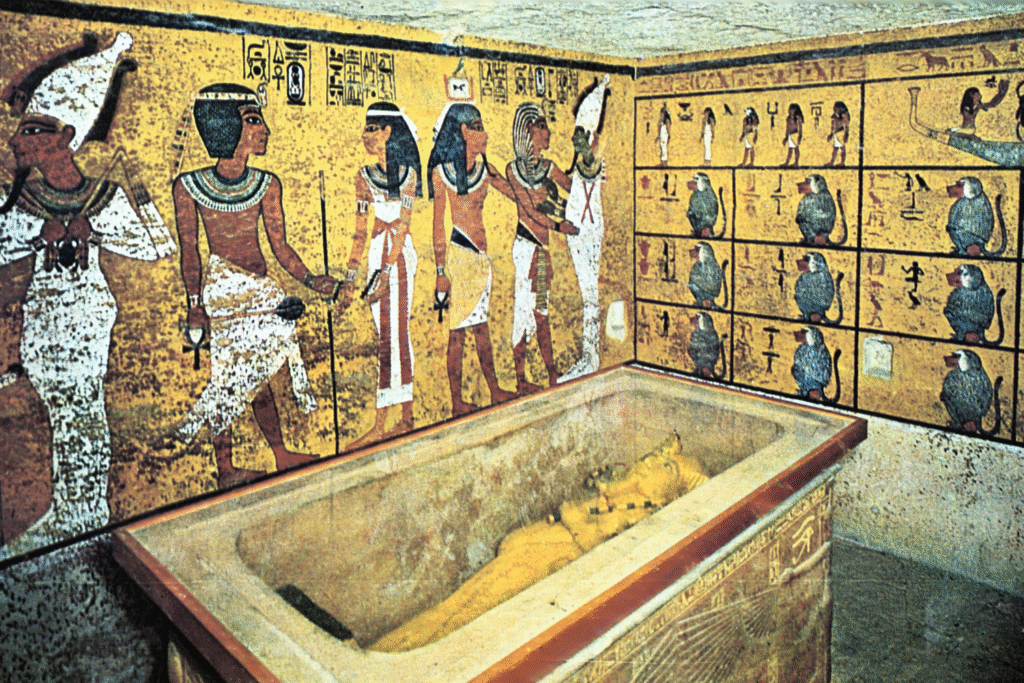

4. Families sometimes buried pets within human tomb complexes.

The interment of pets alongside human owners illustrates how emotional bonds translated into ritual practice. In cases where a beloved pet died, the animal might be included in the owner’s tomb, emphasising ongoing companionship in the afterlife. This practice suggests that pets were valued not just as status symbols but as emotional participants in the family unit. Their inclusion in burial contexts reflects how Egyptians anathematised loyalty, affection and memory. This nuance challenges earlier views that saw animal mummification mainly as commerce or cult, instead showing domestic devotion as part of the picture.

5. Large cemeteries of animals illustrate scale and economy of ritual practice.

Excavations have uncovered massive concentrations of animal mummies—hundreds of thousands or even millions—especially feline and canine examples. Such volume points to a structured industry of breeding, embalming and ritual offering. This scale implies that animal mummification functioned as a significant economic and religious institution. The convergence of temple services, breeding farms and consumer demand created a system where animals were mass-produced for the sacred market. As a result, pets, sacred creatures and votive animals became entwined in regional economies and religious networks.

6. Pets served as symbolic embodiments of deities and protective spirits.

Some animals in life were regarded as the living incarnations of gods—cats linked to Bastet, hawks to Horus, dogs to Anubis—and their death and mummification amplified ritual power. Their preservation carried meaning beyond companionship; it became a bridge to the divine. When pets assumed that role while alive, their burial became part of larger cosmological systems where animal life participated in temple worship and afterlife protection. Recognising pets in this light deepens our appreciation of how everyday relationships mirrored and participated in religious frameworks.

7. Scientific imaging reveals life histories of mummified animals.

Non-invasive scanning techniques on animal mummies are uncovering surprising details: ages at death, cause of death, breeding patterns and treatment before mummification. A study used micro-CT technology to discover that certain cat mummies died young and had their necks broken, while other animals were deliberately bred for the purpose of offering. Such findings shift narratives about pets and reveal facets of ritual practice, economy and animal welfare in ancient Egypt. The revelations transform mummies into living histories of animals that once carried both spiritual and societal weight.

8. The geographic spread of pet burials offers insight into regional variations.

Animal mummies are not limited to one site but are found across Egypt, temple cemeteries, discursive necropolises and domestic chambers alike. Variation in species, burial context and treatment reflect local customs, economic access and religious affiliations. Some regions emphasised certain animals more than others, revealing diverse networks of production and worship. Observing these patterns helps scholars trace how pet and animal mummification practices evolved and localised, moving beyond monolithic models of Egyptian ritual towards rich regional dynamics.

9. Pet mummification invites reconsideration of human-animal relationships.

Examining how Egyptians treated their beloved animals deepens our understanding of emotional, social and ritual bonds between humans and animals. Pets were cherished, sacrificed, dedicated and buried within complex systems of belief that valued them as more than property. This perspective prompts a reappraisal of ancient Egyptian society where animal life played active roles in memory, identity and ritual. As a result, mummified pets become more than archaeological oddities—they become vital evidence of how humans honoured their companions, believed in their presence beyond death and integrated them into sacred landscapes.