A submerged coastline is forcing historians to rethink timelines.

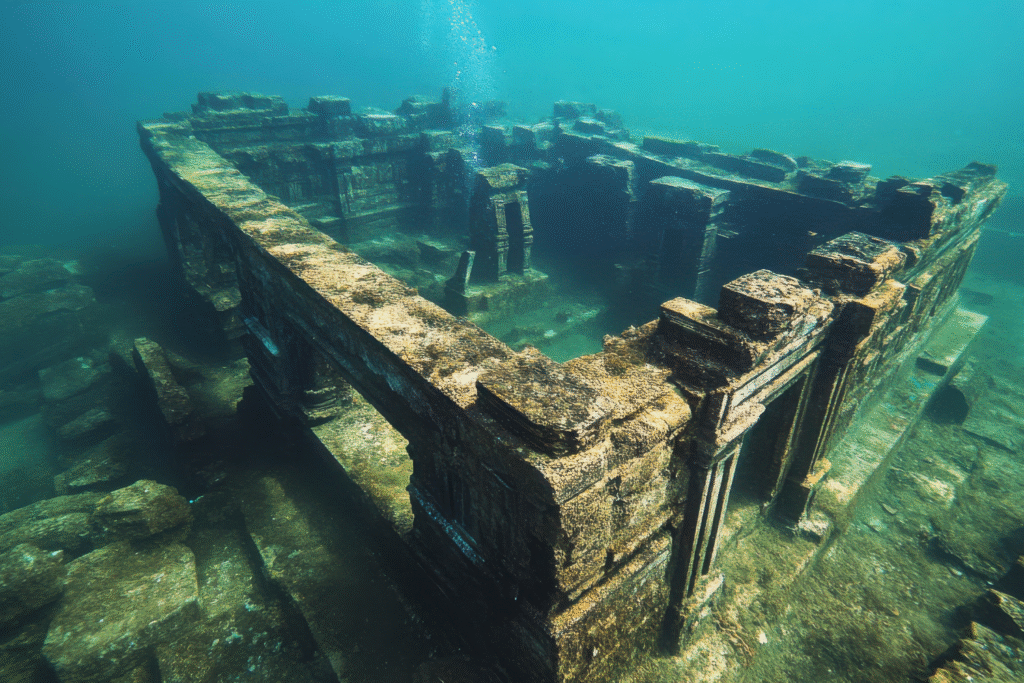

In 2024, archaeologists surveying shallow waters off the coast of western France encountered something that immediately disrupted expectations. Beneath the Atlantic, where waves now pass without resistance, lay a long stone structure shaped by human hands. It was not a shipwreck or a scatter of rocks. It was a wall, built on land that no longer exists. Dating evidence places it thousands of years before many known settlements, suggesting early coastal societies were far more organized and technically capable than previously believed.

1. The wall sits off Brittany’s ancient shoreline.

The structure lies in the Bay of Audierne along the Finistère coast of Brittany, an area that was dry land during the early Neolithic period. At the time of construction, sea levels were significantly lower, and the coastline extended far beyond its modern boundary. What is now seabed was once a working coastal landscape shaped by human activity.

Marine surveys indicate the wall was built roughly seven thousand years ago, placing it around 5000 BCE, according to BBC News. This was a period of rapid environmental change following the last Ice Age. The location strongly suggests the builders lived alongside the structure, using it as part of their daily survival rather than abandoning it to encroaching water immediately after construction.

2. Systematic underwater mapping led to its discovery.

The wall was identified during a planned marine archaeology campaign focused on submerged prehistoric landscapes rather than shipwrecks. Researchers used sonar mapping to scan shallow coastal waters where ancient shorelines are known to have existed. The linear anomaly stood out immediately against the surrounding seabed.

Divers were sent down to investigate and confirmed that the stones were deliberately placed rather than randomly deposited. The formation showed consistent alignment and scale that ruled out natural processes, as reported by Smithsonian Magazine. Measurements and mapping revealed a coherent structure extending across the seabed, prompting further investigation into its purpose and age.

3. Radiocarbon dating anchored the wall in deep prehistory.

Because stone itself cannot be radiocarbon dated, researchers focused on organic material trapped within sediment layers surrounding the wall. Shell fragments, plant remains, and associated deposits provided a reliable timeline for when the structure was built and used.

Laboratory analysis placed construction firmly in the early Neolithic era, thousands of years before written history in the region. This timing aligns with known patterns of coastal settlement before rising seas reshaped Europe’s shorelines, as reported by France24. The dating confirms the wall was not a later addition submerged by chance, but a purposeful structure built in a landscape that humans once actively managed.

4. Stone arrangement rules out natural geological formation.

The wall’s geometry immediately distinguishes it from natural rock formations. Stones are aligned in a continuous line with deliberate spacing and orientation that does not match nearby seabed geology. Surrounding rocks appear scattered and irregular, lacking any comparable structure.

Geological assessment confirms wave action, sediment movement, or ice transport could not have produced such consistency. The stones were sourced locally, but their placement reflects intentional design. This distinction matters because it confirms human agency. The wall represents a constructed solution to environmental conditions, not a coincidental feature later interpreted as meaningful.

5. Archaeologists believe it functioned as a fish weir.

Based on location, height, and alignment, researchers strongly suspect the wall functioned as a fish weir. These structures exploit tidal movement, allowing fish to enter shallow areas during high tide and trapping them as water recedes. The Brittany wall sits precisely where tidal flow would have concentrated marine life.

Fish weirs are known from later prehistoric contexts, but rarely preserved this early or this clearly. The scale of the structure suggests it supported repeated use rather than occasional harvesting. This interpretation aligns with evidence of coastal subsistence strategies already emerging among Neolithic communities in western Europe.

6. Builders demonstrated advanced environmental understanding.

Constructing a functional structure in a tidal zone requires intimate knowledge of water movement, seasonal change, and shoreline behavior. The wall’s placement indicates its builders understood how tides, currents, and sediment would interact with stone over time.

Rather than avoiding the coast, these communities engineered within it. That challenges the idea that early coastal groups were transient or unsophisticated. The wall reflects planning, experimentation, and adaptation in response to environmental pressure, showing that early humans actively shaped landscapes instead of merely reacting to them.

7. Evidence suggests the wall was maintained over time.

Close inspection of the stones revealed signs that some had been repositioned rather than placed once and left untouched. This suggests the wall was maintained, repaired, or modified as conditions changed. Maintenance implies long term value rather than a short lived experiment.

Sustained upkeep requires shared knowledge and coordinated labor across seasons or generations. That level of continuity points to established community structures. The wall was not symbolic. It was practical, relied upon, and worth preserving through effort, reinforcing its role as part of everyday life rather than a one time construction.

8. Submersion preserved details lost on land sites.

As sea levels rose, the wall was gradually covered by sediment and water, creating low oxygen conditions that slowed erosion. Unlike land based sites exposed to weather, agriculture, and development, the submerged structure remained largely intact.

This preservation allows archaeologists to study construction techniques with unusual clarity. Comparable structures on land may have vanished completely. In this case, rising seas acted as an archive rather than a destroyer, protecting a record of human activity that would otherwise be lost to time.

9. The find challenges accepted timelines of engineering.

Conventional archaeological narratives place complex coastal engineering much later in human history. This wall predates many known examples by thousands of years, forcing a reassessment of when organized construction emerged.

The discovery suggests early innovation may have occurred along coastlines rather than inland monuments. Coastal environments demanded immediate solutions for food and survival, driving engineering earlier than previously assumed. This shifts how archaeologists think about where complexity first appeared in human societies.

10. Similar drowned structures may exist worldwide.

Post Ice Age sea level rise submerged vast stretches of prehistoric coastline across the globe. Many early human settlements now lie underwater, unexplored due to technological limits until recent decades.

Researchers believe the Brittany wall is unlikely to be unique. As sonar mapping and underwater exploration expand, more submerged structures may emerge. Each discovery adds detail to early human history, suggesting that some of humanity’s earliest engineering achievements remain hidden beneath modern seas, waiting to be rediscovered.