The diagnosis no one expects at two years old.

For decades, feline diabetes was largely associated with older, overweight cats edging into middle age. Now veterinarians across North America and parts of Europe are reporting something different. Cats barely out of kittenhood are arriving with elevated blood glucose levels, increased thirst, and unexplained weight changes. The pattern is subtle but persistent. Clinics are not calling it a crisis yet. Still, the age shift is raising uncomfortable questions about what has changed inside modern homes.

1. Indoor lifestyles have dramatically reduced activity levels.

In the United States and United Kingdom, the majority of pet cats now live entirely indoors. That shift protects them from cars and predators, but it also limits natural movement. Many young cats spend most of the day resting in small apartments with minimal stimulation.

Reduced activity affects insulin sensitivity. When muscles remain inactive, glucose uptake decreases, placing strain on pancreatic function. Over time, this imbalance can accelerate metabolic changes previously associated with older animals, compressing timelines in ways veterinarians did not commonly observe two decades ago.

2. High carbohydrate diets strain feline metabolism.

Commercial dry kibble often contains significant carbohydrate content to maintain structure and shelf stability. Cats, as obligate carnivores, evolved on protein rich prey with minimal starch. Yet many young cats consume diets where carbohydrates comprise a substantial portion of calories.

Frequent exposure to elevated glucose loads can stress pancreatic beta cells responsible for insulin production. Veterinary endocrinologists have noted that long term high glycemic diets may contribute to earlier insulin resistance, particularly when paired with reduced physical activity and excess body weight in domestic environments.

3. Obesity rates are rising among young cats.

Veterinary surveys estimate that over half of domestic cats in the United States are overweight or obese. Alarmingly, excess weight is now common in cats under five years old. Early obesity increases the likelihood of metabolic disorders appearing sooner.

Fat tissue alters hormone signaling and contributes to insulin resistance. Younger cats carrying extra weight may develop impaired glucose regulation earlier than previous generations. The age of onset is shifting alongside weight trends, suggesting that lifestyle factors are influencing disease timelines.

4. Neutering alters hormonal balance and appetite.

Spaying and neutering reduce reproductive hormones that influence metabolism and appetite regulation. After surgery, many cats experience increased hunger while expending fewer calories. Without dietary adjustments, weight gain can occur rapidly.

In younger cats, this hormonal shift may compound other risk factors. Owners often underestimate caloric needs after sterilization procedures. The metabolic slowdown, combined with high calorie feeding practices, creates conditions that favor insulin resistance earlier in life.

5. Certain breeds show genetic susceptibility.

Studies indicate that Burmese cats, particularly in Australia and parts of the United Kingdom, have higher incidence rates of diabetes compared to other breeds. Genetic predisposition appears to influence how glucose is processed.

While most affected cats are mixed breed, breed specific vulnerability highlights underlying biological variability. When genetic sensitivity intersects with modern feeding and lifestyle habits, younger onset becomes more plausible in susceptible populations.

6. Stress hormones may influence glucose regulation.

Chronic stress elevates cortisol levels, which in turn raise blood glucose. Indoor cats exposed to environmental instability, multi cat competition, or limited enrichment may experience ongoing low grade stress.

While stress alone does not cause diabetes, it can exacerbate metabolic strain. Veterinary behaviorists note that enriched environments with vertical space and predictable routines may support healthier physiological responses in susceptible cats.

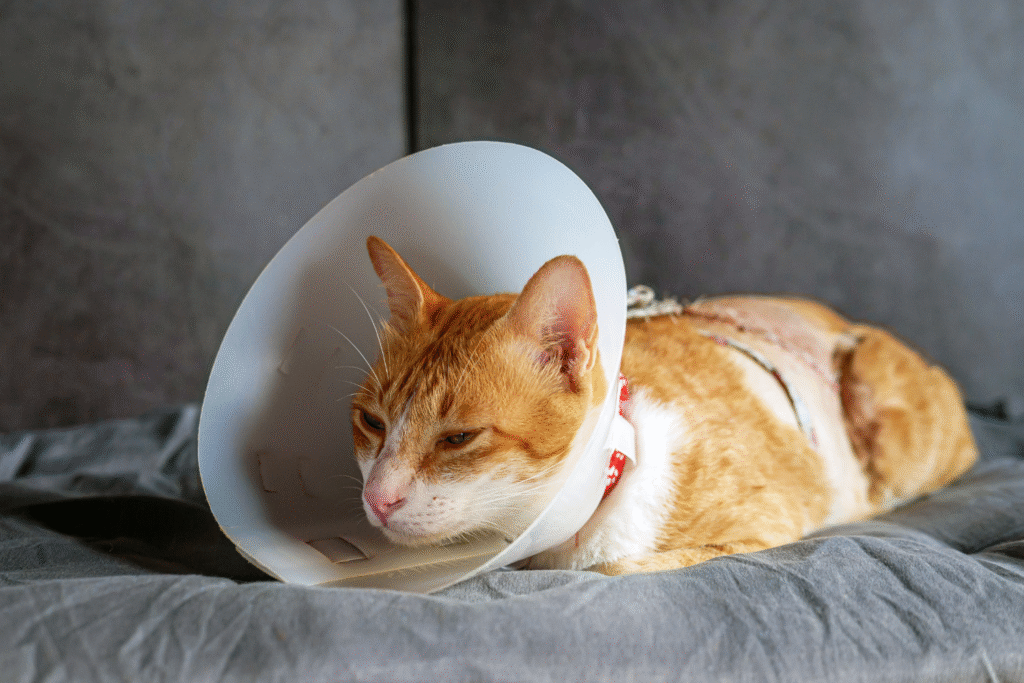

7. Early steroid treatments can disrupt insulin function.

Corticosteroids are commonly prescribed for allergies, inflammatory bowel disease, and asthma in cats. While effective, prolonged use can interfere with insulin sensitivity.

Young cats receiving repeated steroid courses may face elevated risk if other factors are present. Veterinarians weigh benefits carefully, yet cumulative metabolic effects are increasingly considered in light of rising early diagnoses.

8. Delayed diagnosis masks earlier progression.

Subtle symptoms in young cats may be dismissed as minor changes. Increased thirst or slight weight loss can go unnoticed in multi pet households. By the time diagnosis occurs, insulin resistance may have been developing quietly for months.

Routine blood work is less common in younger animals, meaning early metabolic shifts may escape detection. Increased awareness among veterinarians is contributing to more frequent testing and earlier identification of abnormal glucose patterns.

9. Portion control often drifts over time.

Free feeding practices allow constant access to food throughout the day. While convenient, this pattern encourages overeating in some cats. Caloric intake gradually exceeds energy expenditure.

Owners may not recognize incremental weight gain until it becomes pronounced. Younger cats with unrestricted feeding habits may reach metabolic tipping points sooner than those on structured meal plans.

10. Environmental enrichment influences metabolic health.

Cats evolved to stalk, chase, and hunt small prey repeatedly. Modern indoor settings rarely replicate that pattern. Lack of interactive play reduces natural glucose utilization.

Structured play sessions using wand toys or puzzle feeders stimulate both physical movement and mental engagement. Clinics promoting enrichment report improved weight control and overall metabolic markers, suggesting that behavior modification can influence disease trajectory.

11. Remission remains possible with early intervention.

Unlike many chronic diseases, feline diabetes can enter remission if addressed promptly. Dietary modification toward higher protein, lower carbohydrate formulations combined with weight reduction may restore insulin sensitivity in some cases.

Veterinarians emphasize early detection and aggressive management in younger cats. While the age of onset appears to be shifting downward, proactive treatment can alter outcomes significantly. The trend is concerning, but it is not irreversible when addressed decisively.