A frozen chamber preserved an older story.

Deep inside an Oregon cave, beneath layers of sediment and mineral buildup, something fragile survived where stone tools and bones often do not. The chamber had remained cold and stable for millennia, protecting organic material rarely preserved from the late Ice Age. When researchers began carefully removing compacted layers, they did not expect textiles. What they found forces archaeologists to reconsider how advanced early North American communities were at the end of the last glacial period.

1. Ice age clothing emerged from Fort Rock Cave.

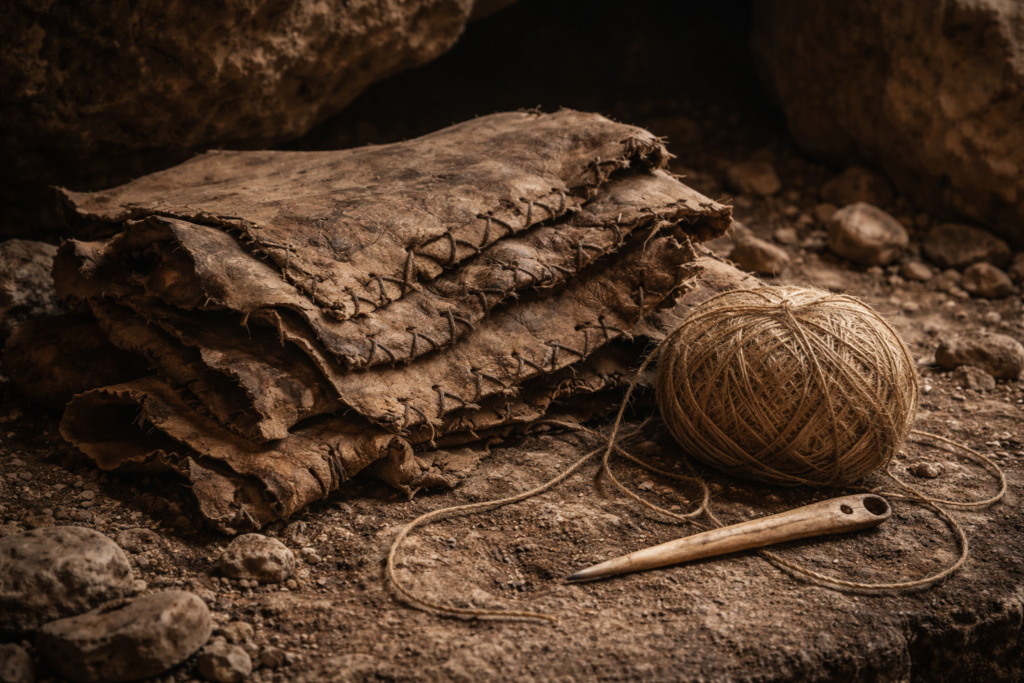

In the 1930s and later renewed studies, Fort Rock Cave in central Oregon yielded fragments of animal hide stitched together with sinew. Radiocarbon testing dated the materials to approximately 12,000 years ago, placing them near the end of the last Ice Age. According to Smithsonian Magazine, these stitched hides represent some of the oldest known examples of tailored clothing in North America.

The discovery predates Egypt’s pyramids by thousands of years. It reveals technological skill in sewing and garment construction far earlier than many assumed for early inhabitants of the Pacific Northwest.

2. The hides were carefully stitched together.

The recovered fragments were not simple wraps. Researchers identified puncture marks spaced in regular intervals, consistent with deliberate stitching using bone or stone awls. The seams indicate fitted construction rather than draped hides.

As reported by National Geographic, analysis suggests sinew thread was used to bind the pieces into wearable garments. This level of tailoring implies planning, tool use, and knowledge of material properties, suggesting Ice Age communities possessed sophisticated survival strategies in harsh climates.

3. The cave’s environment preserved rare organics.

Organic materials rarely survive twelve millennia in open air. Fort Rock Cave’s dry, insulated conditions created an unusual preservation pocket that shielded fragile hide from decay.

According to the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History, controlled excavation and storage conditions prevented contamination and allowed radiocarbon dating to confirm the late Pleistocene age. Without the cave’s stable environment, the evidence of early clothing technology might have vanished entirely.

4. The timing aligns with climatic transition.

Around 12,000 years ago, glaciers were retreating and ecosystems were shifting across North America. Communities adapted to fluctuating temperatures and migrating animal populations.

Tailored clothing would have provided insulation during cold spells and mobility during seasonal movement. The garments suggest resilience during a period of environmental instability rather than primitive survival.

5. The discovery challenges outdated narratives.

For decades, early North American populations were portrayed primarily as big game hunters with limited technological complexity. Organic craftsmanship was assumed minimal due to lack of surviving evidence.

The Fort Rock hides complicate that narrative. They demonstrate knowledge of sewing techniques, hide preparation, and clothing design, expanding understanding of cultural development at the end of the Ice Age.

6. Sewing tools likely accompanied the garments.

Although the hides survived, associated tools may not have endured in the same condition. Bone needles and awls, if present, could have deteriorated or been removed during earlier excavations.

However, puncture spacing and seam consistency strongly imply specialized tools were used. The precision indicates repeated practice rather than experimentation, suggesting clothing production was established within the community.

7. Mobility demanded advanced clothing solutions.

Ice Age populations in the Pacific Northwest likely traveled seasonally between resource zones. Durable garments would have been essential for movement across variable terrain.

Stitched hides provide greater flexibility and thermal efficiency than simple wraps. Their construction reflects adaptation to both mobility and climate, reinforcing the idea of organized survival strategies.

8. The find connects to broader Great Basin evidence.

Other sites in the Great Basin region have produced early woven sandals and fiber artifacts. Together with Fort Rock Cave, these discoveries indicate complex material culture at the close of the Pleistocene.

This regional pattern strengthens the argument that early western North American societies developed textile and clothing traditions independently and early in their history.

9. Radiocarbon dating confirmed ancient origins.

Multiple samples from the hides underwent radiocarbon testing to establish age. The results that came back consistently placed the material around 12,000 years before present, confirming the ancient origin of the material.

The consistency of dates across fragments supports authenticity and minimizes the likelihood of later contamination. The garments belong firmly to the terminal Ice Age period.

10. Early North American life appears more complex.

The Oregon cave discovery expands what is known about daily life at the end of the last glaciation. Clothing construction requires planning, skill, and knowledge transmission.

Rather than isolated survivalists, these communities appear technologically adaptive and culturally organized. The stitched hides from Fort Rock Cave suggest a narrative of ingenuity and resilience that predates monumental architecture elsewhere in the world by thousands of years.